Fiona Sampson MBE FRSL is a British poet and writer, published in thirty-seven languages, and the recipient of a number of national and international awards for her writing. She has published twenty-nine books, including poetry, translations and books on the writing process, as well as a book about Limestone Country. Fiona’s critically acclaimed new biography In Search of Mary Shelley: The Girl Who Wrote Frankenstein is published to coincide with the 200th anniversary of Frankenstein’s first publication.

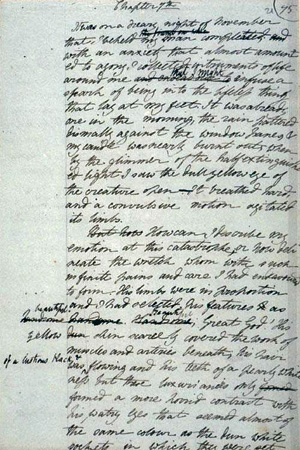

“…Frankenstein was first published on 1st January 1818 by a small specialist press, so it didn’t arrive in a blaze of publicity. It was also published anonymously, to protect Mary’s identity as a woman…”

A lifelong love of writing

I can’t remember a time when I didn’t want to be a writer; although like many girls in my teens I was taught this was impossible. You had to be a dead white male to be important enough to write. And you had to go to an important school, and have an exciting, privileged life. What did I, going to my local state school and living in a dull provincial town, have to say? And yet the burning sense of wanting to say it never went away…

I hope things are slightly better for girls in school now, both in terms of gender and every other kind of identity and background. But I’m not really certain they are. For every one-off outreach project, there’s another library that closes, or a school that dumps its library in favour of more computers. Which are great for information, and all the things that mean we’re hooked into them, but not for reading.

So long story short I was a musician first of all; and then I spent years creating access to writing in hospitals and social care settings; and then I became a poet and worked a lot internationally. But I always still wanted to write prose books, and now I’ve started doing that too.

Structuring my work

I am a ferocious planner and time manager. I break down a big project, like a full-length book I know will take me two or three years, into chapters, and I plan out the months ahead, building in first research, then first draft, then rewriting then editing time. When I’m writing, I go for 1,000 words a day. I write shorter pieces, for example essays for newspapers, in the same way.

Marking the 200th anniversary of the publication of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein

Mary Shelley was born in 1797 and died in 1851. She was the daughter of feminist Mary Wollstonecraft – who died as a result of her birth – and revolutionary philosopher William Godwin, and she grew up in a house full of radicals.

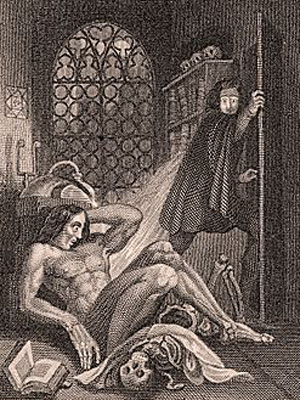

At sixteen she eloped with the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, embarking on a passionate relationship that was lived on the move across Britain and Europe. Before her early widowhood, Mary had already experienced debt, infidelity, and the deaths of three of her children. It was against this dramatic backdrop – and while she was still a teenager – that she composed the cultural landmark that is Frankenstein.

After she was widowed she raised her surviving son, Percy Florence, with little support from either her own family or her in-laws, and she did so largely through supporting herself as a writer at a time when it was unusual for a woman to do so.

Inspiration for Frankenstein

Mary may have written the story because of her own experiences of birth and losing a child, her mother’s death as a result of her birth, and the suicides of her half-sister and of Percy’s first wife while she was writing it. But its immediate trigger was a writing competition organised by Lord Byron, who was a friend, in Geneva in the summer of 1816.

The competition, to write a ghost story, was itself triggered both by the friends’ reading of ghost stories and by a discussion they had about the secret of life, of animation itself. The other famous outcome of this competition was The Vampyre, a short story by Byron’s doctor, John Polidori, which was the first in the vampire fiction genre.

Reaction to Frankenstein

Frankenstein was first published on 1st January 1818 by a small specialist press, so it didn’t arrive in a blaze of publicity. It was also published anonymously, to protect Mary’s identity as a woman.

In fact, the novel was her second book: her first, a travel book, got if anything slightly better reviews. For despite Mary’s anonymity it was clear that Frankenstein was written by one of the radicals in her father’s coterie. Both its experimental subject matter and its way of telling the story made this clear.

Since Godwin’s and his followers’ ideas had admirers but also enemies, reviews were polarised along these lines. The book received a good (but also anonymous) review from Sir Walter Scott. However, by the summer it was a word of mouth success. Within five years, two full-length adaptations would open on the West End stage and it had become a cliché in common use.

Questions about contemporary themes such as artificial intelligence and genetic modification

It’s possible to read the story of the creature who is created and brought to life entirely by Frankenstein acting alone as a prediction of robotics and AI, and / or gene therapy. The sense is that today’s scientists, like Frankenstein, are creating something that is unnatural and so in some fundamental way in a different category from “us”, yet is a thinking thing with independent agency.

I think this is true, but that the applications of Mary’s parable are wider than this. It also asks us more generally to contemplate the risks we create when we innovate scientifically. This is partly because there’s a second story in the novel, about an Artic explorer who’s prepared to endanger his crew in pursuit of scientific glory.

Advice for aspiring female writers

My first tip for girls and women who are interested in writing is to read and read and read! It’s certainly what Mary herself did, and this explains why she was able to write such an amazing, influential book at such a young age. She had already been consuming books and practicing writing for years.

If it’s too expensive to buy books, go to second hand and charity shops, especially Oxfam who has a wide range of good books, not just airport tat. And join your local library: that way everything you read is free and you can afford to experiment by borrowing books you wouldn’t risk money on. The public libraries in the towns I grew up in are the only thing that I had to make me into a writer: I grew up in a house largely without books (and I had an English teacher who hated me).

The point about reading is partly that it gets your ear in – it’s the most effortless way to learn how to write – and partly that it makes you sure about what kind of books you like to read and therefore will want to write. There’s no point even trying to write a book in a genre (say, horror, or literary nature writing) if you don’t like that stuff: even if it looks astute in market terms.

You simply won’t write something that you don’t love well enough, and you won’t have enough to fuel you for the long haul of writing a book. No one wants to read an exercise: everyone, from editors to readers, wants to be engaged, thrilled, lifted up and carried someplace. Pick what you do love instead (say, utopian science fiction, or travel writing).

My second tip is to start small. Practice with articles and short stories for local and specialist magazines. Getting in professional print (obviously, I’m including digital print: i.e. things that are edited and curated by someone else, someone professional) still matters more than anything else, as an apprenticeship and as proof that you are doing that apprenticeship. You’ll quickly learn what you’re good at: summarising / finding the human angle / humour.

Coming up next

Right now, I’m writing a libretto for an opera about Daedalus, with Philip Grange. I’ve always wanted to write a libretto, and this myth is about hubris in the same way as Frankenstein is. I’ve also been working on a half hour radio poem about mud for BBC Radio 4, which goes out on Easter Day. And I’m doing lots and lots of Mary Shelley lectures and talks, in the UK but also in Italy, Sweden, the Balkans and the US. In fact, you can find the listings here.

http://www.fionasampson.co.uk/

https://twitter.com/@fionarsampson

https://www.facebook.com/fiona.sampson.794

Main image credit: By Reginald Easton (Bodleian Library) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Frankenstein draft image credit: By Mary Shelley (1797-1851) (http://www.bodley.ox.ac.uk/dept/scwmss/frank2.html) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Frankenstein frontispiece image credit: By Theodore Von Holst (1810-1844) (Tate Britain. Private collection, Bath.) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons