Claire-Marie Mur’Tala is a Ph.D. student in graphene for biomedicine and bone tissue engineering regeneration at Manchester Metropolitan University. She has a bachelor’s degree in biomedical science and completed a master’s degree in regenerative medicine, both from Manchester Metropolitan University. Before this, Claire gained a Health Care Diploma in Health and Social Care from Bury Enterprise College.

“…being a mum does not affect my ability to work. It is not a disability, it is part of who I am…”

Before academia

Before coming to academia my career was focussed on working in early years (birth to five years-old) and primary to secondary school (five to 16 years-old), in a range of support roles for children with special educational needs. My specialism was English for speakers of other languages / speech and language, and behavioural problems.

However, in 2010/11 after the birth of Tobi (my third child) I became very ill, and after a year of investigation I was diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease – distal colitis. Instead of following some self-help books I decided that if I want to be able to beat the disease (properly), and be well enough to look after the children, I needed to educate myself.

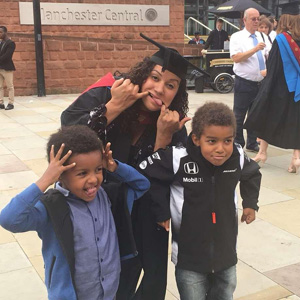

I enrolled on an access to higher education course – under the healthcare pathway at Bury College. I started in May 2012, and after a few weeks, discovered I was pregnant with child number four. Happily, I managed to finish the diploma with a distinction and a fourth child! Following this I was able to enrol at Manchester Metropolitan University on a biomedical science degree.

Being a mature student

The first three years were interesting and challenging. I felt being a mature student had me at a disadvantage because I completed my GCSEs in May 1999, so you can imagine the challenges I faced trying to remember everything from over 15 years ago while my peers were fresh out of college, with all the newer science they learned in the last two years fresh in their heads. While my peers would be able to study a topic for a few hours, I would have to work through the night, or get to uni at 4 am (so I could leave in time to do the afternoon school run) and do my pre-reading.

Pre-reading typically involved taking a concept, reading it on BBC Bitesize, Hank Green’s Crash Course YouTube videos, progressing to Armando Hasudungans’ YouTube tutorials, and text books. I would need to do this before I could even begin to try and understand the lecture notes for every single topic / lecture. It was painfully slow.

However, somehow, I managed to earn Academic Achievement Bursaries for the first two years, and in the summer before third year I applied for and won a Wellcome Trust Summer Studentship in Biomedical Science with another lecture. So, I guess the hard work paid off!

Discovering bone engineering

In my 3rd year I had the chance to work with demineralised extracellular matrix hydrogels developed by the University of Nottingham, and mesenchymal stem cells for bone tissue engineering. I learned a lot of techniques and skills and obtained a 1st for my dissertation.

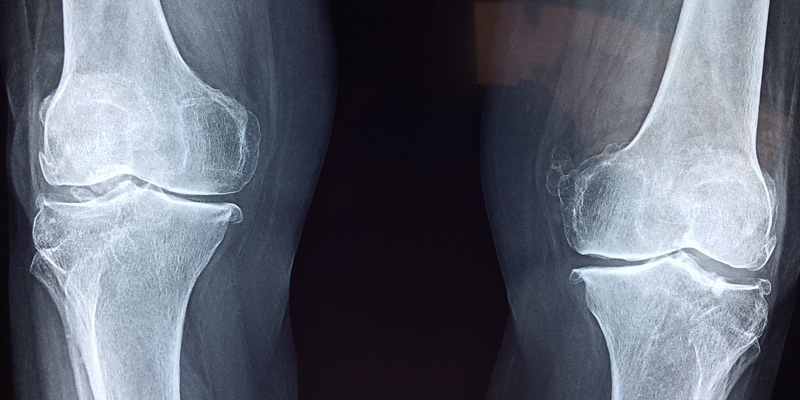

However, bone wasn’t really my first choice – microbiology, and translational medicine in gastrointestinal studies were, but the main schools with research in that area were too far to for me to commute. However, it soon emerged that my last born may have osteogenesis imperfecta, a bone condition that results in easily broken bones. He had three breaks in the first 18 months of life. So, I changed my careers ideas and formally entered the bone engineering route.

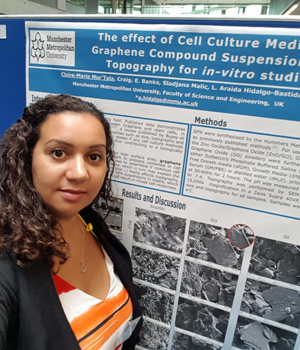

For the master’s year I was given some carbon allotropes and graphene samples, and I had to explore the world of material sciences, quantum physics and detailed maths. (To complicate things further, I have dyscalculia, triggered by learning difficulties). What’s more, at the time there was no mentor for the graphene work, everything I know about graphene is self-taught.

Let’s just say it was intellectually challenging because working with graphene meant that I had to continuously optimise all my protocols preparing for in-vitro toxicity studies using stem cells. On doing this I discovered some interesting things on how graphene interacts with biology.

Being a woman in science is hard and we must support each other

I didn’t think I had done anything amazing – I felt like I was wasting my time in the labs. So, I was surprised when my supervisor asked me to create abstracts for a few conferences, on the various aspects of my work. I was accepted to four conferences, although I had to withdraw from one.

I presented at the Tissue and Cell Engineering Conference, Bioinspired Conference, and Graphene Week 2017. I was also granted a scholarship from Graphene Flagship. It was also on the back of this work that I was given a scholarship at Manchester Metropolitan University for a Ph.D. to carry on these studies.

My academic career has been heavily guided by two main factors – firstly my personal circumstances, which have taken me out of my comfort zones, but I seem to be doing OK, while also enjoying it. Secondly by my supervisor, who took a shine to me, and told me on one of our first meetings that being a woman in science is hard, and we must support each other – and she did.

My role on a day to day basis

My days vary a lot! I have a normal working contract, with holidays as with any job and most other Ph.D. studentships. However, because I have slow processing skills I tend to do more hours, but that’s OK. I love that no single day is ever the same. I don’t cope with change well, but I am pretty much in charge of my hours. I love it!

If I am office based, I sometimes have the flexibility of working from home (this way I can make up lost time with the children from being in the labs). I can usually fit the tasks I need to complete between 9.30am and 2.30pm. I also give support to the undergraduates if they need it, answer emails, chase up suppliers, and work on my reviews.

There are often weekly one to one meetings, and monthly team meetings too. I also find kind people who can help me understand concepts that are new to me. They sometimes listen to my interpretations and discuss them with me too. This really helps my learning process. What I do is so niche that there are few people I can talk to about it.

If I am in the lab typically I would arrive to the office gather my lab books and marker pens before going to the lab. I tend to put in long days, arriving around 7am and leaving at 8pm. Luckily, lab work only lasts at most a few weeks with the first week being the most intense. In between lab weeks there is time to be office based to write up. The schedules rule my day. I take lunch and breaks during incubation times.

Trying to re-grow bone in the lab

When my children ask me what I do I tell them I am trying to re-grow bone in the lab using graphene. Bone is quite remarkable. It can regrow and heal on its own. But there are times when the ability to repair is limited – this could be because a break is too large, for example, or a person has bones that are so thin and brittle.

Sometimes the demands of the body to make more bone is too much for the bone to keep up with – think of a supply and demand process – there just isn’t enough of what we need, and too much being taken away at once. In these instances, medical help is needed. This could be using medications or surgery. Sometimes surgery may not fix the problem and implants made of metal are used. No one likes surgery, it causes a lot of pain, people get infections, and sometimes the surgeries need to be done in stages.

Possibilities from bone engineering and using graphene in biomedicine

The reason many cell biologists are looking at graphene is that it has lots of characteristics that may support human health.

Bone disorders may require supporting scaffolds or complete replacement to be repaired, the scaffolds and implants are often made out of glass, or metals. The metals used are strong, conductive, easily moulded into various shapes, not toxic to humans. Metals also contribute to more bone loss over the long term, and metal can be expensive to obtain.

Graphene has properties that mimic metals, and it is made from carbon, the element of life. The ability of graphene to allow electrical pulses pass over it means that it could be useful in applications where electrical impulses are key to the function of that organ, for example in cardiac and neuronal tissues. Bone is also electrically conductive, very strong and flexible.

Graphene has been shown to be able to withstand the impact of supersonic projectiles – it can stretch up to 20% its own size, can be folded like origami, and has been shown to support some stem growth. There are also a few studies that may suggest potential antimicrobial activity of graphene. Imagine how truly awesome that would be for antibiotic resistance!

However, at this stage the use of graphene in cell studies for human health are still in their infancy and many studies find conflicting results. I have my own theories on this but there is dire need of graphene standardisation, which the Graphene Flagship research initiative is working towards.

Challenging gender stereotypes in science

I have never understood why people look at others and pick a trait or feature to define that person. I see everyone as a person. Yes, some may be older or younger, may have different body parts, or even various skin tones. You cannot ignore that, you make the necessary considerations if / where needed. These things don’t define them, they are but a small, albeit obvious, part of who they are. We should be defined by the core of who we are, not by how we look.

As a parent I use relatable objects to explain things to my children (and well, everyone really) – the example I use all the time is LEGO.

You are given a pack of LEGO to build, so you follow the instructions and accidentally miss a step, but don’t realise straight away, you soon get to point where you can no longer continue to build. Now you have three choices:

- You can try and move a few bits a round to make it fit

- You can un-build it back to the previous building stage and start re-building

- Quit

If you go with step two, yes, it is annoying to think that you must undo all the work you just spent a certain amount of time on, but you can rebuild without any issues. And step three? Well, nothing will ever be achieved from not trying will it? It is better to try something and get it wrong – at least that way we have a tool to work with, to improve things. I think the same applies when trying to address how to fix the problem in science.

On the face of it, when asked about gender stereotypes in science, images where most professors are male, and those who work more closely with students are female spring to mind. Gender stereotypes are a Catch 22 situation and is way more than how we see each other in the work place.

Considering gender differences

I was completely surprised to learn from the book by Angela Saini, Inferior – How Science Got Women Wrong – that most scientific research and clinical trials use males alone (animal and human). The book challenged a lot of what I was taught in the last four years at university, in a very logical way.

I subsequently noticed that many of the smaller undergraduate studies around campus would request male volunteers and I was shocked at how pronounced this was. Now you could argue that these are just small undergraduate studies, but if at this level gender differences are not even considered, then what hope do we have at making studies translatable at the higher levels?

Tackling gender stereotypes by working with children

In the broader scope of things, we need to completely re-build what we have built already, just like step two of the LEGO analogy above. I believe that to tackle any gender stereotypes anywhere, we need to work with the children, from the early years and I feel that Vygotsky’s work goes a long way in supporting this.

Studies have shown gender stereotyping begins in the early years instigated by adults. Children pick up their personal values and conceptions about themselves and others as they grow and try to figure out where they stand in the world, and this is influenced by their environments.

If children can see their parents actively taking on roles that not are typically associated with what we traditionally expect, it allows them to accept a new normal e.g. Mum is up the ladders changing the lightbulbs, while Dad is loading the dishwasher. We cannot easily re-train adult’s minds to be different as easily as we can with children.

Generation by generation progress

There needs to be a period of transition and it will take a few generations to get it right. Each time we have something to build on to make it better. Once children accept each other as equals then by the time they get to research level, including women in trials would be an innate part of the study, not something to consider.

When my children want to do something but have doubts I tell them it is OK. If one of them suggests than another cannot do something I challenge them and encourage them to challenge each other. My Elisa is very good at playing devil’s advocate with them now and encourages them all to ask questions.

They tell me I am ninja and compare me to Wonder Woman, because they see me challenge things when I don’t see the logic behind it. My point is that we need to teach the children, in the home and outside.

I am Mummy, the #Ninja of #Awesomeness 😎 and #Fire🔥 #justsaying #lovethem #yesIknowson 💪🏽 pic.twitter.com/0AuTUhuxw4

— Claire Nuttegg (@ClaireNuttegg) January 29, 2018

Being an #AcademicMama of four

I have four children – two girls and two boys in high school and primary who think I am awesome and that I know everything about everything there is to know. It’s a good confidence boost, as I often think I am failing at everything.

The children often help me with my work. For my master’s year I thought I had a problem with the graphene – I needed to obtain a dried uniform product for imaging. Adele my second eldest said: “Mum, why don’t you just sieve it, and put it on the radiator?” And there was my “Virginia Durr Moment”.

I have been so involved with the quantum theories and learning new techniques and was so completely baffled I did not see the obvious. I used a syringe filter and put it in the oven. I think as adults sometimes we tend think things have to be complicated and try to make things complicated for no reason – sometimes the answer is just much simpler than we think.

OMG – how do you do it?

Generally, I feel that men get an easier ride when they announce their parenting duties. They get this unspoken air of respect from colleagues, for being a “hands-on dad” (regardless of the number of children they are responsible for) – something I have never experienced being a mum, although now that I have four children I sometimes get: “Well, you don’t look like you have four kids”, and the “OMG – how do you do it?”.

My partner never gets that – when they realise he has four children the respect for him grows a million-fold! He gets a pat on the back, and no questions asked if he needs to leave work at 2.30pm to do the school run. But this is not limited to the academic field.

In my 3rd year at university I got this feeling that some staff felt I was somehow not as focussed and committed as others. It was not a direct feeling, it was very passive. I would be asked if I could manage the workloads (and I felt it was directly linked to my parenting status, because at some point in that conversation the children would be brought up, although not by me).

I told my supervisor and other lectures not to tell anyone at meetings I had children. In my final degree year, and for part of my master’s year I refused to let anyone know I was a parent at all, and definitely not to four children. I feel I have more pressure to make sure I work harder just to get the same level of respect.

I also sometimes feel that female colleagues with no children seem to be treated slightly more favourably than working mums – they get invited to drinks after work etc. Recently I was even reminded that my role as a mother should not be allowed to interfere with my work.

Overcoming self-doubt

However, by the time I graduated, a male colleague, Glenn Ferris, told me that I have achieved more than most undergrads, M.Sc. students and even some early Ph.D. student supervisees, getting into conferences, winning awards, scholarships and bursaries. He said I should be proud of that, because I did that with children – four of them.

The way he spoke with total respect, and not shock, made me realise that maybe I have achieved something good. I often don’t realise that I have achieved things – I feel like I am failing at everything, and people need to point it out to me all the time.

I am constantly doubting myself and how others viewed me. At the beginning of the Ph.D. I tried to resign because I was left feeling inadequate by some comments from a few male colleagues who blatantly told me I shouldn’t be in science. (The same male colleagues who said this to me last year too).

I told my supervisor I couldn’t do it and I would have to quit because I have the children and I was worried it would clash. She reminded me of our first meeting, and gave me a pep talk, finishing with how we would work it out between us because I am a good student.

So, if I face a situation where I feel my children are being brought into something, or my integrity is being questioned, I now have my own mantra.

I have competed a B.Sc. and an M.Sc. with a learning difficulty that causes symptoms of dyscalculia, yet I still got the highest grades and won scholarships and bursaries, despite having four children. Two of my children are autistic, and one of them has osteogenesis imperfecta, yet I have never missed a deadline, and spent a large chunk of my time mentoring other students above me. So, being a mum does not affect my ability to work. It is not a disability, it is part of who I am.

Advice to other women (and also men) juggling science careers with family commitments

First of all, I do not sugar coat things. People need to have realistic expectations, otherwise they are being set up to fail. If you ask my opinion, you will get my truth. Working in science will be hard. It is academically and mentally challenging. You need to compromise on where and how you spend your time. You may have to work long hours at uni and into the night at home.

You may be occasionally late for school pickups, you will be tired and cranky, and long for the weekends. But you know what you have in common with someone who isn’t a parent? All these things. Even those without children have to go through this.

As parents we have to catch up with the children, do homework, feign enough energy to play with them and do house work. But that doesn’t just relate to working in science. That relates to any job a parent would do. Not everyone has someone else to rely on, and even if you did, most of the time you would rather do it yourself.

You need to be organised. The children will always need stability and routine (let’s face it, so do most adults). And everyone needs to develop something that will work for them. This means that it may take a whole semester, or longer to get it right. So, there will be judgement errors along the way. And that is 100% OK.

I have a weekly timetable. On Sunday I look my work schedule and Tee’s, as well as the commitments and appointments the children have, and we figure it out. It’s called winging it until it works! We now have a family calendar in Google, and our general rule is whoever does the morning school run, the other does the afternoon.

If one of us has a lighter day, that person does both morning and afternoon, so the other can catch up on hours. If one of us (usually me) has few weeks (when I’m in labs) where we need long the days the other tries as hard as possible to cover them, and over the following weeks we then let the other catch up. Tee works with me to make this work for us both. And then there is Friday…

Talk it out

One of the key things I found that helps is talking to the children. Children just do not want to be left feeling like they are being ignored and are not important. When you respect them as people with minds and brains of their own, they understand and generally go much easier on you for not being home.

They will plan and cherish the time you do share, so its real quality time, not “I hate you for not being home” time full of guilt and regret. I share the calendar with them, I tell them what I will be doing that day that prevents me from coming in home.

Sometimes we let them have input with the calendar – some days they may want one of us home for help with something, so we try to manage the hours around that. I have given them an old phone which they leave in the dining room, so they can call or text me or Tee when we are not home. They like that because they know they can get hold of us when they need to.

Coming up next

I have just start my Ph.D.so I just need to get through the first year for now! I have learned not to overthink things and just to plan the foreseeable. I have however registered as a STEM Ambassador, so I aim to try and put something back into schools, mostly primary.

The Sylvia Pankhurst Centre is holding some events for International Women’s Day 2018 and has sponsored me to put some activities on alongside their own events so I’d love Womanthology readers to come along.

https://www.linkedin.com/in/claire-marie-mur-tala-5896a8108/