Dr Duncan Brown is an author, researcher and government adviser with 30 years’ experience working in major HR consultancies and employment institutes. He also spent five years as the deputy CEO at the CIPD. His clients have included Shell, the Cabinet Office, the Department of Health, Unicef UK and the Fairtrade Foundation.

“Employers need to hire and promote more people of colour and women at all levels; pay them equally; use their capital to invest in minority entrepreneurs and communities; and use their lobbying power to support policies and politicians that will advance equality.”

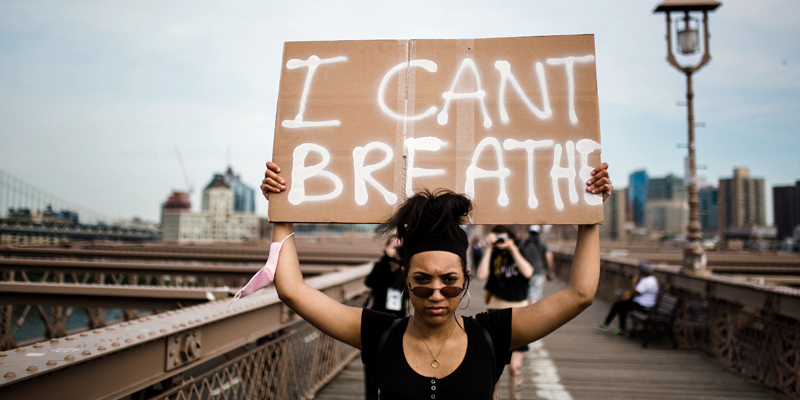

Black Lives Matter

The callous murder of George Floyd at the end of May 2020 sparked a remarkable protest movement against a panoply of racial and intertwining economic injustices and unfairness, that as democratic chair of the Congressional Black Caucus and author of their comprehensive police reform bill, Karen Bass put it, ‘has caught fire, is multiracial and has spread around the world’.

A lot more exciting than your average corporate board’s diversity discussion. If they ever have one that is. ‘We are building a more inclusive and diverse group of individuals within our company, who will be much better equipped in dealing with the changing and challenging nature of our world and environment’ says the white chairman (and it is a man of course) of one of my corporate clients in their latest annual report and accounts. But how, how well and how fast are they doing this?

The Black Lives Matter movement has left governments and employers exposed, highlighting the common gap between their espoused support for equality on Twitter and in corporate value statements and HR diversity policies; alongside their often-limited action in putting these principles and policies into practice.

A diversion from gender?

There is also a reasonable basis in evidence to indicate that the creation of the integrated Equality and Human Rights Commission in 2007 has led to the loss of focus and effective action within the individual equality strands such as race and gender, although a decade of public sector austerity cuts almost certainly help to explain any loss of power and expertise.

The influential House of Commons’ Women and Equality Committee was highly critical of the EHRC in 2019 for its lack of enforcement of existing gender equality legislation, arguing that employers therefore routinely felt able to discriminate against women ‘with impunity’ and that EHRC ‘must overcome its timidity and be bolder in using the existing powers that only it has’.

Many HR and diversity professionals argue that they can only resource and address one or two aspects of diversity at a time in their already resource-stretched and fast-changing organisations, even before COVID-19 hit them , with one telling me that since the 2017 compulsory pay reporting regulations, ‘gender is the only game in town here’.

Slow Voluntary Progress

Yet employers, politicians and lawyers need to recognise the intertwining and mutually reinforcing aspects of these different dimensions of inequality and discrimination, which the academics refer to as ‘intersectionality’, as well as many of the solutions.

If addressed, the tragedy of George Floyd can help to engender much wider action on unfairness and inequality and support the required legislative and institutional and systemic changes needed within employers on race, gender and all aspects of diversity.

These ‘intertwining injustices’ of gender and race inequality at the hands of what I heard described in a recent webinar as ‘white male pay and positional privilege’ produce a powerful evidence base and motivation for change on both fronts.

Following Boris Johnson’s announcement last month of yet another review into racial inequality, Ruby McGregor Smith, author of a government review of racial disparities in employment three years ago which made 26 recommendations for action, called on the government to implement them in full, including extending the gender pay reporting regulations which were finally introduced in 2017 to encompass compulsory ethnicity pay reporting. The resulting public consultation I responded to on the best methods for ethnicity pay reporting closed 18 months ago, but the government still has not bothered to respond.

Yet even the token voluntary target resulting from the parallel Parker Review of ‘One (BAME board member) by (20)21’ in every FTSE100 company looks likely to be missed by more than a third of them, with only 11 new ethnic monitory director appointments over this period. It’s a similar if not quite so bad story on gender diversity in our largest companies.

The Investment Association last month attacked Aston Martin and Dominos Pizzas for returning to all-male boards which ‘should have no place in the FTSE 350 in 2020’. More than a hundred companies still lag behind the voluntary target of a third of directors being female by 2021, and the majority of them are in non-executive roles and support functions. Perhaps most remarkably, the removal of Karen Hubbard as chief executive of retailer Card Factory in late June means that there is not a single retailer in the FTSE 350 with a female leader, even though the sectors’ workforce and customer base is two-thirds female.

Race, gender and COVID-19

At the other end of the employment and pay hierarchy, the pandemic has almost certainly worsened both gender and ethnic inequalities, as well as highlighting the threadbare nature of the remaining welfare and social security net after a decade of austerity cuts. The majority of the growing numbers of children living in poverty in this country are in families with working parents, and at age seven the proportion for black kids is double that of white kids.

The differentially awful impact of COVID-19 on the poor, women, the young and ethnic minorities is now well-known, recognised and subject to deeper investigation. Fiona [Tatton] and I responded jointly in April to the parliamentary inquiry launched into this, Unequal impact: Coronavirus (COVID-19) and the impact on people with protected characteristics.

Both women and BAME people are heavily over-represented in the ranks of the lowest-paid and increasingly insecure, zero-hours contract workers in health and social care, cleaning, retail and similar occupations. To this has been added in recent months the correspondingly higher risks of being exposed to and dying from COVID-19 in such roles.

Carol Jamabo, a 56-year-old mum of two with an ‘uplifting, joyful and enthusing personality’, a keyworker for 25 years who had been working for Cherish Elderly Care in Bury, became the first care worker to die from catching the virus on 1 April. She had no savings. The £4,500 cost of her funeral was raised for her family in less than 24 hours on the Go Fund Me charity website.

14% of the population is BAME but they have represented, according to the Kings Fund, 34% of critically ill COVID-19 patients and 64% of the deaths of NHS staff so far from it. According to new Fawcett Society research, 43% of BAME women and 48% of BAME men say that they had lost government support in the past three months, compared with 13% of white women and 21% of white men.

More than four in ten BAME women said they would struggle to make ends meet over the next three months, reporting high levels of anxiety about having to go out to work during the pandemic; and not surprisingly, they have the lowest life satisfaction and happiness levels of any ethnic and gender group.

According to the Institute of Race Relations, the average white household has £221,000 in assets, the average black African household £15,000. While I heard the Archbishop of Canterbury on the radio this morning optimistically arguing that our shared experience of the pandemic will induce a greater focus on fairness and equality, I tend towards agreeing more with Alaana Linney, Commercial Director at BUPA. On another webinar I spoke on recently, Alaana described equality as having taken ‘a big step backwards’ over the last three months as far as female and BAME employees are concerned.

Witness the government’s disastrous decision to suspend the gender pay reporting regulations a week before the annual deadline in April, meaning that only half of employers have actually published their pay gaps figures this year.

As well as being completely unnecessary when employers had had more than 11 and a half months to calculate and analyse the required statistics, it not only gave out totally the wrong message about equality’s importance, but also could have a disastrous impact on the progressive ratcheting up of the pressure on firms to act on their gaps since the measures were introduced in 2017.

Initial analyses of the published reports suggests that stronger not weaker action and enforcement is required. The overall finding emerging from an excellent recent analysis of the published reports by my friend Aidan Crossey is that: ‘The gender pay gap is shown to have widened between April 2018 and April 2019, from a median 9.6% to 10.6%’; leading him to conclude that ‘the current (necessary and commendable) focus on managing the societal and economic implications of the coronavirus crisis has tended to marginalise analysis of many other important societal and employment trends, including gender pay inequality’.

The worrying wider implication is that post-pandemic, equality matters will need to take a back-seat so to speak to ‘more important’ economic matters, The financial pressures after such a steep and rapid recession during lockdown are likely now to magnify the overwhelming pressures on businesses to keep costs down and government to find people jobs on whatever terms they can get.

‘When a million more people are on the dole, does anyone think it will be a priority to publish gender pay gaps?’ asked influential Conservative MP Daniel Hannan pointedly in the Daily Telegraph. He clearly thinks not. Helen Lewis similarly fears that the economic recession resulting from this pandemic is likely be ‘a disaster’ for women, describing how the recent SARS epidemic in Africa reversed the prior gains in women’s relative earnings and more equal sharing with partners of home and family care work.

What blocks? White (male) fragility?

In thinking about the sorts of solutions that Fiona and I recommended to the WEC inquiry to address the risks of growing gender and racial inequality, I have increasingly recognised that my own career and work has focused far more heavily on addressing gender inequality in pay and employment.

So, one of my personal resolutions in the wake of the Floyd killing has been to learn more about ethnic inequality in employment and how best to address it, with half of black Britons reporting that they have suffered racism at work in the most recent study I could find.

One concept I have found really useful and with equal relevance I feel to gender, is that of ‘white fragility’. Hiding behind our equality policies, diversity strategies and politically correct terminology, as I found facilitating consultations on the ethnicity pay reporting proposals of the government, many of us in HR are uncomfortable – and using best-selling author and sociologist Robin Diangelo’s term, ‘fragile’ – about discussing our ‘white privilege’ and the often unrecognised racism that goes with it in our organisations.

Behind this ‘disbelieving defensiveness’ as Diangelo calls it, we prefer to attribute inequality to a complex historic cocktail of economic, social and cultural conditions that we are often powerless to influence, rather than admitting that black people are paid less and are far less evident at the top of our organisations than white people because of the colour of their skin.

Whilst HR circles have long since used the BAME rather than ‘black’ terminology, she attacks the mnemonic for its obscurity and lack of specificity about what we are really talking about here.

The same reaction can often be seen in terms of white male executive reactions to evidence in national data on continuing gender discrimination – ‘it’s a historic problem’ (but one that’s still evident in new graduate pay levels); ‘it’s a social problem that needs to be addressed in schools’ (so why aren’t you out there helping schools address it?); it’s not evident in this organisation (even though the vast majority of employers still have unrepresentative boards and gender pay gaps favouring men).

‘Gender pay gaps are being kept alive by men who think they are dead’ was the conclusion of a recent study funded by the British Veterinary Association led by Dr Christoher Begeny at the University of Exeter. They identified systemic bias in the performance ratings and pay of male and female vets, with managers of clinics who believed that gender bias no longer exists in the profession most likely to rate identical performance descriptions for men more highly than women, resulting in an average pay gap in awards of 8%. Dr Begeny argues that only the compulsory ‘guard rails’ of removing names from job and promotion applications will prevent such discrimination.

However well-meaning we ‘white allies’ may be in HR, progress on race and gender equality in this country has largely been driven by ‘direct action’ in the forms of legislation and compulsion, not voluntarism and employer HR and diversity policies, and we almost certainly need more of it.

What works? Government and employer actions

So how can we then best address this growing and intertwining inequality on the basis of gender and race in employment? My research and report of what is currently being done and the findings of prior research studies for the EHRC to draw out the lessons on ‘what works’ in closing gender and ethnicity pay gaps highlighted: a relative lack of research on race; and also some evidence that measures successfully taken to improve female representation and pay gaps appears to have had less impact on racial divides.

But on both aspects of diversity, we found the predominant HR actions focusing in the ‘easier’, ‘softer’ areas of voluntary Unconscious Bias Training and similar developmental and attitudinal initiatives, which is what Robin Diangelo ran unsuccessfully for 20 years while developing her thesis; and which have a mixed record in academic research at best.

‘Harder’ and more resource-intensive, compulsory changes – blind recruitment, compulsory representation on selection panels and shortlists; and other ‘diversity by design’ initiatives recommended by Harvard professor Iris Bohnet and supported by her research, were far less apparent pre-pandemic, yet have much stronger research evidence in support of their impact and effectiveness.

According to Diangelo, to progress we need to listen, to display ‘humility and vigilance’ and to ‘be clearer, try harder and do better’. We in HR need to get out there and listen to people’s perceptions and experiences of racism – in our employers, in schools, in wider society. We need to acknowledge its continuing presence and we need ourselves to behave with that recognition – speaking up when there are no black or female faces round senior tables or on selection panels for example.

And then we need to get more attention and resources to addressing the issue with a multi-pronged, sustained approach, addressing the divisive structures and processes in our organisations as well as culture and behaviours; and extending well beyond Diangelo’s ineffective diversity training programmes.

Employers need to hire and promote more people of colour and women at all levels; pay them equally; use their capital to invest in minority entrepreneurs and communities; and use their lobbying power to support policies and politicians that will advance equality.

Government should continue to promote voluntary adherence to higher minimum employment and diversity standards and improvements such as the London Mayor’s Good Work Standard and Greater Manchester Good Employment Charter. IES’s research on pay and career progression for majority-female lesser skilled workers across different sectors and countries suggests that even when subject to intense financial and pricing pressure, not investing in employees is a false economy, due to the increased indirect costs resulting from employee turnover and low staff satisfaction.

Fiona and I agree with the CIPD and many investor groups such as PIRC, that compulsory gender pay reporting should be extended not just to cover ethnicity but compulsory annual publication of a dashboard of a much wider variety of human capital metrics, as part of an enhanced ESG reporting requirement – including: the diversity breakdown of workforce, numbers on part time, fixed term and zero hours contracts, numbers paid the national living wage, and so on.

The strengthening of employment standards and legislation was already occurring to some extent pre-coronavirus, with the government’s Mathew-Taylor inspired ‘Good Work’ consultations and reforms already well underway, following his landmark 2017 report, including fair pay, safety and security, improved labour market protection and enforcement.

Taylor believes COVID-19 will add impetus to the concept of good work, saying that, ‘The crisis has led us to recognise the importance of jobs that might previously have been seen as low status as well as low paid: social carers, supermarket workers, delivery drivers’. The crisis should we hope stimulate much more widespread support for stronger measures under his ‘good work’ agenda in the forthcoming employment bill.

Improved definition and communication of employment status and rights already in train needs to be a foundation for wider changes, such as the removal of the confusing ‘worker’ status. One-way contractual flexibility and token board representation by a non-executive director need to be replaced by genuinely two-way contractual negotiation, meaningful worker representation and far more extensive employee participation and ownership.

There needs to be a statutory right to a permanent contract after 26 weeks, rather than just the proposed right to request one which was the subject of a recent consultation exercise.

Around one quarter of tribunal awards against employers at the moment go unpaid, highlighting the weak state of UK labour market enforcement, which the WEC highlighted in its recent report on equality enforcement. The UK needs a much better resourced and powerful single enforcement body, following the example of countries such as Ireland.

Be hopeful, take action

50 years after the original Equal Pay Act, the progress on gender and race equality in the UK has been frustrating and ponderous. But the killing of George Floyd; and the experience of the pandemic to highlight what the Pope has called ‘the bashfulness of poverty’, has undoubtedly given it fresh impetus.

This needs to be directed towards addressing the systemic causes of this inequality and unfairness, with stronger employment legislation and enforcement, and more compulsion in employers, particular to control for often unwitting bias in selection and pay decisions.

The pandemic has certainly stimulated much greater awareness of inequality of all types. As we celebrate the launch of Womanthology’s new branding and website, let’s hope that the timing is now opportune in the wake of these two horrendous events; and that this also promotes more comprehensive and widespread action by employers in areas that actually work in closing gender and racial pay and opportunity gaps.

The Reverend Al Sharpton in his eulogy at George Floyd’s memorial service sent goose-bumps down my spine as he concluded it with hope: ‘I’m more hopeful today than ever. Why? Well, let me go back. Reverend Jackson always taught me, stay on your text, go back to my text, Ecclesiastes. There is a time and a season, and when I looked this time, and saw marches where in some cases young whites outnumbered the blacks marching, I know that it’s a different time and a different season. When I look and saw people in Germany marching for George Floyd, it’s a different time and a different season. When they went in front of the Parliament in London, England and said it’s a different time and a different season, I come to tell you, this is the time’.