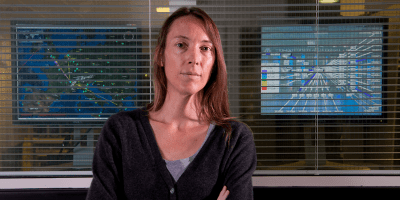

Vanessa Madu is a PhD student at the EPSRC Centre for Doctoral Training (CDT) in Modern Statistics and Statistical Machine Learning (StatML) at Imperial College London. Vanessa is passionate about better understanding our oceans and their influence on our climate; her research involves integrating techniques from machine learning, time series, and spatial statistics with physics-inspired models to model ocean surface currents and understand how they transport floating objects. Vanessa is also a talented science communicator and inclusion champion, and she has received several awards for her unique, innovative, and successful approaches to making science accessible to general and young audiences.

“The intention of attracting more women into science and STEM is important, but it’s not where I can make my most valuable contribution. Rather than talking about women in science and STEM, my preferred way to go about this is to *be* a woman in science, maths, and STEM.”

From mathematics to modelling oceans

My name is Vanessa, and I am a PhD student in the StatML CDT, a joint programme between Imperial College London and the University of Oxford; I am based at Imperial.

I also did my MSci in Mathematics at Imperial. The first year of my degree was turbulent for me. I spent a lot of time questioning if maths was what I wanted to do or if I wanted to follow a more applied route, so I strongly considered changing my degree to mechanical engineering, going so far as to apply for a degree transfer. However, my first mathematical research project at the end of that year made it undoubtedly clear that I was and am a mathematician (with applied inclinations).

My PhD research reflects this journey of self-discovery and is about as applied as one can get while remaining in the maths department; I use maths to understand our oceans. But, before we get into that, I want to step back for a moment and set the context with an (abridged) version of how I got here in the first place; the story starts at a comprehensive state school in the east of London.

My secondary school experience was challenging for several reasons, almost all tracing back, in some way, to my ‘unusual’ interest in maths. There were significant logistical issues in enriching my mathematical talent, chief of which being that one of the subjects I needed to apply for a maths degree, further maths, not being available to me as a full A-Level, so some self-teaching was involved.

However, what is also evident in that account is the social isolation I was experiencing at school, albeit a sanitised version. I couldn’t wait to go to university because: “I will be in the best place for geeking out in interested company about the newest mathematical concept that I’ve come across, which I really look forward to!”

I was right about finding my people at university but less right about where I would find them. For the keenest of readers who gave my 2018 article even a cursory glance, you’ll find much jubilation about an offer to study Mathematics at Trinity College Cambridge I had received. I missed the offer; I achieved stellar A-Levels but missed the STEP requirement. It genuinely felt like my world was ending and that everything I had worked for had been pulled out from under me; I didn’t think I’d ever recover. I did recover, and missing that offer ended up being one of the best things to ever happen to me because being at Imperial and being in London had me well-placed to do both of the things I love most — doing science and sharing it.

Statistically speaking

As part of a maths degree, I developed a strong understanding of numbers, complex systems, and everything you think a mathematician would be doing; I also did some mathematical physics. I learnt concepts and ideas from across applied maths, which can all be concisely summarised as: “the universe’s language is mathematics”, and through my mathematical education, I developed a mathematical toolbox to understand how various things in real life work. (More on this shortly!)

Then there was statistics, which taught me that there’s an inherent randomness in everything that happens on the Earth; unfortunately, due to the consequences of my actions, that’s about all I had learned about it until near the final year of my degree. But recall, I am doing a PhD in Statistics; this is a funny story.

More of a statistician than I thought

When I reached the fourth year of my degree, I became acutely aware that my statistics skills weren’t great. I decided it would be very embarrassing to graduate from a ‘world-class institution’ with a master’s degree in mathematics and not have a grasp of probability and statistics. To remedy this mild indiscretion, I decided to take one statistics module and settled on time series analysis.

A time series is a series of measurements taken over time. Usually, the times are equally spaced, so if I wanted to know what the wind was doing at Imperial, I’d stand in the middle of Queen’s Lawn, and I’d record my wind measurement today, tomorrow and then the day after and the day after that, and so on. That series of measurements taken over time is a time series, and investigating the properties of those time series to work out information about the processes generating them is called time series analysis. It was fascinating, and I enjoyed it far more than I anticipated.

Around this time, I was doing my final year project on the clustering behaviour of floating objects on the ocean surface, like plastic, plankton, and all sorts of things. The curious thing was I kept trying to apply time series techniques and the new statistical concepts I’d learned to my project. At that point, I realised I might be more of a statistician than I thought.

It dawned on me that statistics is a very clever way of understanding how the world works, with the acknowledgement that we can never be entirely certain about our predictions. It was amazing, and I wanted to learn everything I could, and that is how I ended up doing a Statistics and Machine Learning PhD. This enthusiasm proved very useful when faced with the exceedingly steep learning curve and the beginning of my PhD. I needed to spend a tremendous amount of time understanding the concepts. But once I got them, I felt as if I had earned the privilege of being a mathematician who sits in the gap between two mathematical sections.

I’m an applied mathematician and a statistician with all the unique expertise and computational skills that come with that combination of titles; a fantastic set of skills for understanding how the world works.

The call of the oceans

I love it when people ask about my research because I love it and find it incredibly exciting! I am interested in predicting ocean surface currents and how things get moved around on the ocean surface. The ocean is incredibly difficult to work with for many reasons. It’s highly complex, and getting out there to measure things is exceptionally challenging (and, as a result, very expensive).

From the surface, it’s opaque. People like to throw around the fact that we know more about space than the deep ocean — it feels ridiculous that we know more about things astronomically far from our planet than the ocean, which makes up 71% of the Earth’s surface. But it’s true. We can’t exactly take a telescope and point it into the deep ocean, so learning about what the ocean does and why it does those things, how it moves objects and how its behaviour changes with climate change needs more creative approaches.

That information is helpful to us as we work to identify where plastic is in the ocean and where it might be going, especially at a time when we’ve got a massive marine plastic problem. Or it could help to track oil spills. The movement of plankton populations is of great interest, too. They produce around 50% of the Earth’s oxygen and get moved around with the surface currents. The movement of nutrients dictates where fish live, and for a considerable proportion of the population of Earth, fish is the primary source of protein; all of these things are interconnected.

Statistics and machine learning come in as there are many different ways to study what the ocean does. Some people go out to take measurements. Then you’ve got other people, like me, who are more inclined to remain on land. We use the data captured at sea and remotely sensed satellite data and then apply statistical models to pick out patterns in our data and explore the relationships between them.

Going back to the beachball I dropped in the ocean, maybe I can use the relationships between all of these different measurements, like the sea surface height, the temperature, wind speed and so on, to develop an understanding of how they are related to the speed of the beach ball at some given time.

Statistical and machine learning models are very good at this. So, with my applied mathematical background, I bring knowledge of how to develop equations to understand how the ocean moves; I have a massive atlas on my desk and photos of various current systems around my office to help with this. Then, I combine that with my developing knowledge of statistical modelling techniques to create models better than the sum of their parts.

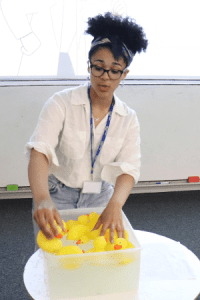

I love the ocean and am passionate about helping people understand its importance because we depend on it. Still, it’s so easy to forget it exists as most humans have very infrequent interactions with it. To help mitigate this, I am doing a lot of science communication, public engagement and outreach alongside my research because science is best shared.

Everyone who wants to be a scientist should be a scientist

I’ve always fancied myself a scientist, wanting to understand why the world does what it does. I am also a mathematician, endlessly fascinated and curious by maths and its ability to encapsulate how the world does what it does, but also to facilitate the creation of art in and of itself, independent of the world around it. Maths is just one of the closest things we have to magic. It’s incredible, and I wish everyone else could see maths the way I do, so I try my best to share the magic I see.

I feel so lucky with how often I say, “I love my job”. It happens at least once a day. Because of this and everything I’ve experienced to get to this point, when it comes to championing STEM, I believe that everyone who wants to be a scientist should be a scientist. Anyone curious about science should at least have the opportunity to fully investigate whether or not being a scientist is for them. That equal opportunity to investigate science, maths, engineering and technology has yet to exist uniformly.

I don’t particularly appreciate using ‘women in STEM’ to describe my champion work because it’s too vague. I do what I do with the vision that anyone who wants to be a scientist should be a scientist, including those whose demographic markers make them less likely to continue science beyond secondary school and who need support to have the same access.

Women typically fall into this bracket and have less exposure to science in an appealing and not prescriptive way. Hence, women get less of a fair shot of fully investigating whether or not science is for us, but this is true of several other minority groups, too. If we only present the dull side of something, then, of course, people aren’t going to consider it as an option for them.

The intention of attracting more women into science and STEM is important, but it’s not where I can make my most valuable contribution. Rather than talking about women in science and STEM, my preferred way to go about this is to *be* a woman in science, maths, and STEM.

I always want to remind people that women in science should advocate for the cause of women in science if they feel called to do this. But, the most valuable contribution a woman in science can give to the cause is to keep working on and sharing her science; we needn’t use words to quote-unquote *justify* our presence in STEM because our work speaks for itself. In the same way that a picture is worth a thousand words, showing women doing their science says infinitely more than women scientists talking about women in science ever could.

For that little girl from East London who doesn’t quite understand what a scientist is and doesn’t see herself in science, if she can see someone like her doing fun science, she might think: “I want to do that.” It’s why I go to schools to share my science through outreach initiatives. Then, she and others like her might find that the idea of becoming a scientist sparks something in them, too.

Celebrating International Day of Girls and Women in Science

There are many reasons why it’s vital to mark days like the International Day of Girls and Women in Science. One of the main reasons is that science is an environment that is still incredibly male-dominated, and that comes with its invisible challenges in terms of how women in science have to carry themselves in these spaces to have their work taken seriously. It’s a challenging set of circumstances to navigate.

So having a day to remind ourselves that there are women and girls in these situations and that they’re excelling is helpful for morale and for having the work we do recognised.

The second reason is a sentiment I expressed earlier: I don’t think it can be overstated how important role models are. When helping someone work out a career trajectory, the most effective way to convince them that what they want is possible is to show them someone who has done it; widely celebrating International Day of Girls and Women in Science does this.

Keep your options open

Vanessa, circa 2018, is the same age as my sister now and thinking about the advice that I’ve given my sister, who is an art, English and politics student, and myself, a budding scientist. The primary thing I’d say is: “Choosing ‘correctly’ right now is less important than you think, but whenever you do make a choice keep as many doors open for as long as you can.”

At the beginning of Year 12, I told my physics teacher I wanted to drop chemistry because it was more challenging than anticipated. The primary reason my teacher advised me not to do this is because my other subjects, maths, further maths and physics, were all very similar to one another (I used to call it “maths, more maths and then applied maths”, which is essentially what that subject combination was!) But chemistry gave me a different skill set that is still useful now. Lab skills are helpful things to have in general. It’s fascinating how easily that translates to baking and cooking. It’s a similar skill set, just with edible ingredients!

There’s way too much pressure on young people to choose correctly. There are many examples of people starting a career trajectory in one direction and changing it later because they realise it’s not for them. We need to normalise it because that’s not a failure. You just learned something by deciding: “This direction isn’t for me.”

Don’t forget about the things you enjoy

You should always make sure that you enjoy what you do. In some sense, it’s a stereotypical piece of advice, a cliche, but there’s a reason for that. It’s the wisest choice you will make because, without the enjoyment, motivation will only get you so far. Parts of my degree made me think: “I just want to be done with this.” But the love of the subject kept me going through those difficult periods to get a good degree.

Coming up next

Coming up next for me, I’m focusing on my PhD because there’s lots to do, but I’m incredibly fortunate to have some really exciting trips coming up, too. I’ll be heading to Atlanta, Georgia, as I’ve received a scholarship to attend the Gathering 4 Gardner Biennial Conference, a celebration of all things recreational mathematics and the legacy of Martin Gardner, who was fantastic at popularising recreational maths through his writing in Scientific American. Following that, I’ll be heading to the National Oceanography Centre in Southampton for an ocean modelling workshop.

Regarding my ambitions for sharing science, I’m branching into written science communication. I’ve been doing lots of writing recently, and I look forward to continuing down that route and establishing a style of communicating science that works for me. I’m rather whimsical, and I share my science to be very reflective of that because it’s fun for me and fundamentally reflects my relationship with science.

I also think people like it when they get to see ‘Vanessa the person’ rather than just ‘Vanessa the scientist’: the Vanessa whose phone home screen picture is a family friend’s cockapoo wrapped in a blanket covered in bees; the Vanessa who commonly uses napkins in restaurants to do maths on them; the Vanessa who has a slight obsession with numbers; the Vanessa whose superpower is mathematics and looks forward to showing the world what she can do.