Dr Helen Meese is the founder and CEO of the Care Machine, a healthcare and MedTech consultancy. Helen was previously head of healthcare at the Institution of Mechanical Engineers (IMechE), focusing on medical equipment, pharmaceutical production, innovative and emerging technologies and how they impact on healthcare, both in the UK and internationally. She has over 20 years’ experience in industrial and academic roles and is passionate about all aspects of technology, engineering and science.

“On average, these sorts of equipment, in terms of numbers of pieces of technology within hospitals, can be anywhere from 20 to 50,000 pieces that those clinical engineers will be responsible for. It’s a huge, very complex job. It’s almost like looking after an aircraft carrier. Therefore, I think the role that they’re playing now is being seriously recognised by the NHS, and I think going forward, as long as we can keep that pressure on, it will be the job to have within the NHS in the coming years.”

Career to date

I am an electromechanical power engineer. I did my degree at Loughborough University and then followed that up with a PhD. I have been in engineering for just over 20 years, both in academia and industry.

I spent a lot of my early career in the defence industry, that’s really where I started, when I was doing research at university, that led to a career in defence. And I’ve worked for a number of big companies, including Babcock International, where I worked on the Euro Fighter, and GE Power, where I worked on electric propulsion systems in South Korea.

I joined the Institution of Mechanical Engineers (IMechE) in 2013, as head of engineering in society, and then later as head of healthcare policy. At the end of 2017, I left the institution and I decided to put my money where my mouth was and set up The Care Machine to provide innovative technology solutions, business management, and training to MedTech start-ups, SMEs and researchers at the very early stage of medical device development.

I’ve worked with a number of companies and universities to develop products and services and guided them through the process. It is a very complex process to develop medical devices.

Across MedTech, I champion the importance of biomedical, pharmaceutical, mechanical engineering and medicine. I’ve written a number of policy statements on the subject and I often speak about the reason why we need engineers in healthcare. I’m also the host of an engineering podcast, called Impulse to Innovation. And I’m vice-chair of the biomedical engineering division at the IMechE.

Our 'Healthcare Solutions: Improving Technology Adoption' report is now available!

— The IMechE Team (@IMechE) September 3, 2020

IMechE are calling for national 'complete life-cycle' strategies for #technology adoption within the #NHS - @Helen_Meese

Read our report: https://t.co/C6R1a4Tgdi#healthcarescience #medtech pic.twitter.com/44NYL9eL1d

Specialising in healthcare as COVID cases are on the rise again

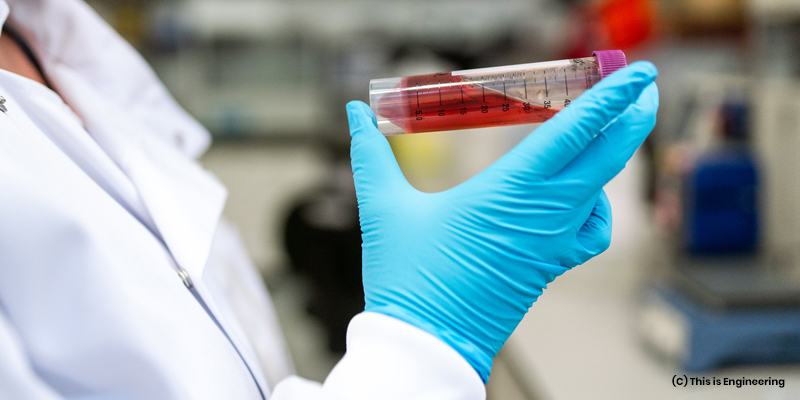

Healthcare has really been a hot policy topic over the last nine months. It’s a field that is on the rise. Everyone’s interested because of the need for medical devices and equipment, so it’s really the place to be at the moment. It’s been a field that’s been growing up over the last, I would say ten years or so, particularly with the number of biomedical engineering degrees that are now coming to the fore in universities.

Rather than doing a straight engineering degree and then going into healthcare later, people are now doing degrees in these subjects. We’re seeing huge growth, particularly in terms of more young women coming into it. I think this is a great area to specialise in right now, although it’s bitter-sweet due to the loss of life brought about by COVID.

Working on the NHS Nightingale hospitals during the COVID outbreak

It’s one of those situations that you just never expect when you pick up the phone. I was originally approached about supporting the London Nightingale Hospital, which was the first one. I literally got a call from one of the healthcare science directors in London. The question was “Where are we going to get more engineers with clinical experience to help deal with potentially thousands of patients?”

We had to go through a very systems-driven approach to understanding what the need was, and how we were going to train the engineers. Importantly, we had to mitigate any risk to them, from a health point of view, in terms of coming to contact with potentially contaminated equipment or people, and also make sure that they were trained well enough so that they weren’t going to make any mistakes. This was quite a long process that we had to go through really quickly.

I started to make a few calls to people I knew. I just thought we’d started off with a few engineers from my own institution and then that grew to people in a couple of the other institutions, and before long I was making a call to the Royal Academy of Engineering about how they might be able to help me to get a message out to all 38 engineering institutions in the UK.

They very kindly helped me by hosting a database so members could register, and we created a very detailed job description. Within 48 hours, we had over 600 people sign up. Over the course of the next month, we had over 1000 people register, which spread out from just dealing with London to dealing with the whole of the UK.

We just got to the point of training the first 20 people to go into London, when the government decided at that point to change the model for the United Kingdom purely because the numbers of patients they were expecting weren’t materialising at that point. But it shows that you can take a project from a blank sheet of paper through to people being on the ground in a matter of weeks.

I could not be prouder of my company @thecaremachine today, featuring in the @RAEngNews new rpt on #engineering responses to #Covid_19. We worked with the #nightingale #healthcarescience team to recruit over 1000 #engineers onto a support database... 1/2https://t.co/XZ86PbU2kB pic.twitter.com/rC6Jpy62Hc

— Dr Helen Meese CEng MIMechE (@Helen_Meese) August 19, 2020

The rise of clinical engineers

Within healthcare science in the NHS, there are about 50,000 people. That’s only about 5% of the workforce within the NHS, but they impact 85% of patient care. So that small body of people has a massive effect on how patients are cared for. And within those 50,000 people, there are only around 3000 clinical engineers across the NHS.

I think the NHS has recognised this as a key role within healthcare, and that they’re going to have a big push to not only increase the numbers of people in healthcare science as a whole, but particularly in clinical engineering. Engineers are responsible for making sure all the medical devices work, that they’re in the right place at the right time for patients. They also develop and design technology. They’re not just fixing and testing equipment and making sure it’s safe and fit for purpose, they’re also using their engineering skills to design and develop devices.

On average, these sorts of equipment, in terms of numbers of pieces of technology within hospitals, can be anywhere from 20 to 50,000 pieces that those clinical engineers will be responsible for. It’s a huge, very complex job. It’s almost like looking after an aircraft carrier, therefore, I think the role that they’re playing now is being seriously recognised by the NHS, and I think going forward, as long as we can keep that pressure on, it will be the job to have within the NHS in the coming years.

My latest projects

I am working on quite a number of projects with universities, within different areas of research. I’m working on a project which is looking at how we keep older people active for longer around home, which is very exciting. Obviously, I’m in my late 40s and I want to ensure that when I get into my dotage, that there’s going to be technology there that will support me and look after me and keep me healthy.

This will be a long-term piece of research, but what the university has recognised is that they need to have people who, by virtue of their experience in industry like me, are able to guide them through that process to make sure that what they’re designing is fit for purpose and that people are going to want to use it. There’s no point to the research if we are not sure it’s going to be a viable product at the end of the day. That’s kind of the reason why I work on a lot of these projects.

At the other end of the scale, I’m working on training and education programmes, again with another university consortium to show clinicians how to take methodologies that engineers have used for years, and apply them to problem-solving within their own working environment.

It’s really exciting to see a clinician suddenly realise that actually there’s a method for solving problems that is really easy to apply. This is a great opportunity for me as an engineer; to share my experiences with people outside of my sphere of professional influence.

https://twitter.com/helen_meese

https://www.linkedin.com/in/drhelenmeese/