Sarah Day is a senior teaching fellow at the National Centre for Prosthetics and Orthotics at the University of Strathclyde, but before this she has also worked in Ireland, Australia, Thailand and Saudi Arabia. Today she teaches biomechanics and clinical skills to undergraduate and postgraduate students to prepare them for work within the prosthetic and orthotic industry, and supervises postgraduate engineering students in their research degrees. Sarah’s main teaching and research interests are in upper limb prosthetics, focusing on the ways that technology can be integrated with the user to improve quality of life.

“There’s a whole load of new technologies out there. Materials are making an enormous difference for us because we’re now able to make prosthetic and orthotic devices that are stronger, lighter and, in many cases, more flexible.”

From Strathclyde to New South Wales

After I left school at 18 I went to the University of Strathclyde, where I studied for a bachelor’s degree in prosthetics and orthotics. I didn’t know much about the course before I went on it, other than it was an engineering course. I also knew that there was a lot of hands-on work, I’d be making things, and that it involved working with people, which were the things that appealed to me. I liked the idea of being able to apply my knowledge in a healthcare environment.

I finished the course in 1999, and my first job was as a prosthetist in a busy department in a large hospital in England. I worked as part of a big team and I got to see loads of exciting technology. I had wide exposure to different types of patients so it was a super start to my career. That’s also where I really started concentrating on upper limb prosthetics, the area I now concentrate on in my practice. After three years there, I got itchy feet and decided to move on. I moved over to Ireland, where I lived for a year and worked as a prosthetist orthotist.

At this point, I decided to pack up and go off travelling for a while, but unfortunately, I ran out of money (as you do!) when I was in Australia because being on the tourist trail was quite expensive. So, always the pragmatist, I opened up the Yellow Pages and found some prosthetic companies. I called up several and I ended up getting jobs in Australia working in prosthetics.

That was my first experience of working overseas in the industry, but it was brilliant, because the exposure to different practices opened up my mind, and I started to think more creatively about the solutions I was coming up with for people.

From Thailand to Saudi Arabia

From there, I decided I quite liked living overseas and I went to work in Thailand for my first teaching role in a new prosthetics and orthotics school that was opening up at a university in Bangkok. I found out about the school from the contacts I’d made in Australia.

I was in Bangkok for two years. I worked alongside a local team to develop the university programme, and taught clinical skills to the students. It was a completely different culture and a lower-income setting than I had previously worked in. We were dealing with different materials, different reasons why patients were coming to us and a lot of challenging cases. There’d be patients with multiple injuries that you’d have to consider, which was really eye-opening. The language barrier was an additional challenge.

From there I moved to Saudi Arabia, where I lived for six years. I went back to a clinical role and ended up managing a large clinical service. There were some very complex cases, language barriers, and a very different culture again. At that point, I was the only female prosthetist orthotist working in the whole of Saudi. Being the only woman in this type of role presented some challenges, but I found the local people very welcoming and it was a wonderful experience.

Homeward bound

I came back to Glasgow in 2012 and I’ve been working at the University of Strathclyde, teaching on the prosthetics and orthotics programme ever since. I love working at universities because I still get to see patients, but I also get to influence the next generation of clinicians who will end up working in the places I’ve worked too.

In Saudi, I worked on a plan to develop the workforce of prosthetists and orthotists and, as a result of that, we’ve had over 30 scholarship students come over, most of them female. Many of these students have now graduated and gone back to Saudi so instead of it being just me like it was, 15 years ago, hopefully now there’s going to be a bit more diversity in the workforce over there.

It’s one of the most rewarding things because I’ve been here for 11 years now, and I’m really starting to see the students I’ve taught now taking up higher positions in the industry. There’s a real sense of pride in seeing someone you’ve trained doing well.

Training the next generation of prosthetists and orthotists

Day-to-day, I teach theoretical and clinical classes, giving students the knowledge and practical skills they need to practice as a prosthetist orthotist. There’s a team of ten of us that work together so we don’t teach every subject. I’ll alternate with colleagues based on a system of teaching blocks, so I’m only teaching one day this week, but last week I taught four days. When I’m not teaching, I do research and admin. I also travel to conferences once or twice a year to present my research or teach courses.

As well as teaching the practical skills of prosthetics and orthotics I teach core background subjects, like biomechanics and anatomy. Some of that is lecture-based and I’ll stand up in front of a PowerPoint presentation. Other times we’ll be working in small groups on patient scenarios. We also invite patients come into our clinical facility at the university so the students can practice the clinical skills of the job on volunteer patients.

About prosthetics and orthotics

A prosthesis is an artificial body part. Prosthetists work with patients who have had a limb amputation or have been born with a limb that’s congenitally different, or absent.

An orthosis is a device that will assist or support a patient. You wear it on your body and it can influence the way that, for example, you stand, or how you might use your limb, either to help you to get more function or to prevent damage from happening to your body.

Examples of orthoses include insoles, leg or hand splints, and spinal braces. So, if someone’s got a curvature of their spine, which sometimes happens in teenagers, we can make a brace that slows down the progression of their curve until they reach an age where they can have corrective surgery. Orthotists work with people with a range of health conditions, from cerebral palsy to diabetes.

Centuries-long evolution

Prosthetic and orthotic devices have been around for centuries. There is a prosthetic toe made by the Egyptians that is over 2000 years old and in a museum. Early prosthetic limbs were made from bronze or wood. The designs became more functional in the Middle Ages and there are stories of knights riding into battle wearing prosthetic arms to hold their shields. Materials such as carbon fibre, silicone, and titanium are now commonly used to make prostheses.

Prostheses and orthoses used to be crafted in workshops by tradesmen, but in the mid-1900s the profession progressed more towards the medical field. A big change came in the early 1970s when the education of prosthetists and orthotists transferred to universities and became a lot more structured and evidence-based.

Prosthetist orthotists are now recognised as allied health professionals, and are regulated by the Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC).

Why Strathclyde is so special

Prosthetics and orthotics is quite a small profession. We’re one of the smallest allied health professions in the UK so we don’t need to train a lot of people every year. The employment opportunities are however very good.

The National Centre for Prosthetics and Orthotics at Strathclyde is the oldest prosthetics and orthotics school in the UK. We were set up around 50 years ago and we take on around 30 new students every year. Strathclyde is one of the main players globally in prosthetics and orthotics, and everywhere that you go around the world, people know about the Strathclyde course. It’s one of the most respected courses in our profession.

When I was travelling, I really benefited from that reputation because when the places I applied to for jobs found out I was a Strathclyde graduate they had me working the next day. It’s been a passport for me to pick up work anywhere.

Over and above this, we are the only prosthetics and orthotics school in the UK that is accredited by the International Society for Prosthetics and Orthotics (ISPO). Our course gets tested every five years to make sure that we are meeting their tough criteria. Holding the highest level of ISPO accreditation means that our graduates are sought after internationally.

We are also the only UK course that offers a four-year degree. The longer course means that we can take our time with the education and training we provide. We are able to offer our students more practical sessions, which means more patient experiences where they can learn in a safe environment before they go out and start treating patients for real. We believe the slower pace increases the quality of education and training.

The profession is a crossover between engineering and medicine. There’s a real art to it and a craft the students have to learn. We make products throughout all four years of the degree. Students see patients, assess them, and then decide what type of device to make for the patient. Then the students fabricate a device, critique the fit, and make improvements to it so there’s a working device at the end of the process. Patient care is at the centre of everything we do.

At the end of the course, students complete a project of their choice, which gives them the opportunity to specialise. Some students might come up with a new solution for a particular clinical problem, others might examine the literature on a particular subject, or they might carry out a survey of patients or an analysis of data, so all the projects are very different, based around the needs of the patients.

Making the profession more reflective of the population it serves

Historically, prosthetics and orthotics was a male-dominated profession, so patients were going to hospitals for treatment and it was only men working there. Some patients felt uncomfortable with this because some of the work that prosthetist orthotists do can be quite intimate.

For example, if someone has had an amputation above their knee, then the prosthesis we’re making them will come right up to the top of their leg. This means we have to look in between their legs to make sure everything’s fitting properly. Or we could be providing a spinal jacket to a teenage girl which might involve her standing in her underwear while we’re fitting it, so it can be quite an intimate experience being fitted for a prosthetic or an orthotic device.

Obviously, clinicians are professional and work within the proper standards we’d expect, but some patients prefer to be fitted by someone of the same gender, so it’s really important that the profession is more reflective of the population, because half our patients are female. More women are now entering our profession. In fact, now, most of our graduates are female, which is great as we try to even up that gender imbalance that’s out there.

I’m not sure it’s as a result of there being more women entering the profession but we’re seeing a move away from treatment being just about the device and how it’s made, and more into how the device and person interact together, so more of a holistic approach.

“Yes, I’m different, and I’m me.”

We used to make prosthetic devices to try to match the patients’ skin tones so they could be hidden, but now people are increasingly wanting to show their devices off. We can make devices in multiple colours, ones that look like superheroes, or give them a robotic appearance so that they become something to be proud of, something to show off and say: “Yes, I’m different, and I’m me.” That’s been a great change in the industry over the last decade.

There’s also a whole load of new technologies out there. Materials are making an enormous difference for us because we’re now able to make prosthetic and orthotic devices that are stronger, lighter and, in many cases, more flexible. That makes them more comfortable for people to wear or makes them function better.

Also, the microprocessor industry has played a massive part, so now we’ve got microprocessor knees, microprocessor ankles, hands and elbows, which all allow people to have more control over the movements in the joints’ devices. It’s not just about the technology coming out, but it’s also about us understanding how to best use the technology and choosing it for the right people and the right applications.

New technology is expensive when it first comes out. We’re lucky in the UK that the NHS funds different prosthetic and orthotic devices. There are ways that NHS funding can be sought for many different devices for UK residents. If people are interested in trying out new technology, I encourage them to contact their prosthetic or orthotic service to discuss their needs and find out the right route.

From an accessibility point of view, the devices that we provide help people to access everything else in society, so someone with the right prescription for a prosthetic leg, for example, then has the freedom to participate in society alongside all of their peers. Without that, their lives could be very different.

Career highlights

Prosthetics has provided me with a colourful and fun career. There have been many opportunities to travel and take part in key events. A highlight for me has been working with paralympic athletes. In 2014 I was able to work with many Paralympians at the Commonwealth Games when they were in Glasgow.

I also work closely with Toni Shaw, a swimmer who uses a prosthetic arm as part of her strength training programme. (See main article image.) The prosthesis allows her to complete exercises including pull-ups, bench presses, handstands, and other exercises involving barbells and dumbbells. She went on to win a bronze at the 2020 Paralympics in Tokyo and a bronze at the 2022 Commonwealth Games in Birmingham.

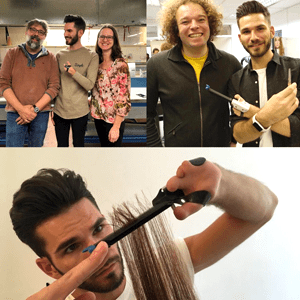

Another career highlight was being on a BBC Programme called The Big Life Fix in 2018, where I was part of a team that created a device for Kyle, a trainee hairdresser who was born with a partially formed hand so that he could pursue his dream career.

Last year I was also honoured to be nominated, and a top-100 Finalist, in the Women’s Engineering Society awards.

Coming up next

I’ve been studying part time for my PhD and I’m due to finish that early next year. It’s about health inequalities. I’m looking forward to getting it finished and releasing my findings.

I’m really excited about what’s ahead for the profession because it’s a great time for the development of technology. Education is also changing and we are finding ways to incorporate technology into our courses so that our graduates are well-prepared to go out into the world and help make a difference.

Reference links

- https://www.linkedin.com/in/sarah-day-59105733/

- https://www.instagram.com/sarahdaypo

- https://www.strath.ac.uk/staff/daysarahmrs/

- https://www.strath.ac.uk/

- https://twitter.com/unistrathclyde

- https://www.instagram.com/unistrathclyde/

- https://www.facebook.com/UniversityOfStrathclyde/

- https://www.linkedin.com/school/university-of-strathclyde/