Dr Becca Wilson is an interdisciplinary researcher with a career spanning the space, atmospheric and health sciences. She is currently at University of Liverpool developing open-source software for the sharing, access and visualisation of sensitive health data based in their Department of Public Health Policy and Systems. Becca holds significant expertise in science communication and public engagement, and she is also passionate about increasing diversity in STEM, particularly amongst ethnic minority groups and people with disabilities, as well as being a disability activist committed to improving inclusivity in the academic sector.

“You have to question why there is an underrepresentation of disabled people in academic careers and what can we do to change this? Clearly, there’s a good proportion of undergraduates identifying as disabled so how can we convince them to pursue a career in academia, whether it’s science or not?”

Searching for dinosaur bones on Mars

I always loved the outdoors. Since about the age of about six or seven, I had real aspirations to be an Indiana Jones-type character, but in space, where I’d be searching for life on other planets. As a child, I thought this was going to actually be finding dinosaur bones on Mars!

As I grew up, I did a geology degree and then I followed that up with a PhD in astrobiology where I got to study how life started on earth, and potentially elsewhere in the solar system. Then I continued working in science in different areas, taking a sidestep from planetary research into atmospheric sciences and then space research.

Then about ten years ago I moved into health data science, which is a very different pivot, but throughout it all, it’s always been science-driven, with the science becoming more computationally and data-intensive over the years.

Researching into population health

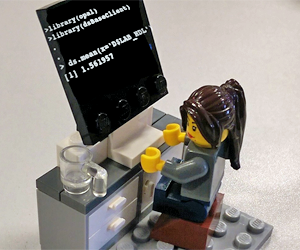

I love those memes you get on social media where it has: “What the public thinks I do”, “What my mother thinks I do”, or “What my professor thinks I do” and then “What I actually do”, because they’re so accurate. The public thinks that for health data science we’re going to be using loads and loads of data, or maybe we’re even using futuristic technology for data analysis, like the screens in the Tom Cruise sci-fi film, Minority Report.

The reality is that I spend pretty much every day at a computer and a lot of time in meetings, often Zoom meetings. I work with a huge amount of people around Europe, as well as in North America and Canada, so the only way really to meet and work on our research is to use virtual tools.

Celebrating the open-source movement in science

There’s been a really big movement over the last ten years or more towards open science, and the idea that scientific research, whether it’s the software that we’re writing in order to analyse the data, tools and methods, as well as our findings, should be available to everyone. It’s also the idea that there shouldn’t be a cost barrier to finding that information, and open-source research software also helps contribute to the reproducibility of our research.

Tools like open-source software allow us to ensure that our research is accessible and free and openly available for everyone to use. The reason why that’s particularly important for software is that cost can be a barrier to using a piece of software to do some data analysis, particularly if you are from less-resourced parts of the world.

Low- and middle-income countries, for example, might have fewer resources for scientific research, and so having the opportunity to utilise pieces of software that are free at the point of use, or that require more basic levels of technology, computers and infrastructure to run that data analysis is always going be beneficial for everyone.

Working collaboratively to shield scientific data from harm

I lead work on a piece of open-source software called DataSHIELD, which is used by researchers in health disciplines to analyse data that’s located in different places around the world, or sometimes even in the same country, but the way that it works is that the data itself is never physically moved and the researcher can never directly view the data.

The software helps users to be compliant with regulations and restrictions in terms of how we handle health data, and so ultimately it helps protect the privacy of the people the data is actually about. This is our contribution to open science. We’re really lucky because we have people from all over the world including low- and middle-income countries that are starting to make use of DataSHIELD — it’s a ‘shield’ to protect user health data from nefarious use.

Science communication: Raising awareness of one of my greatest passions

For me, my love of science communication always takes me back to this really strong memory of the exact point in time when I knew I wanted to pursue a science career. I was age six, and it was my first trip to the Natural History Museum in London. When you go somewhere like that as a child, you’re just filled with all this exciting and wondrous stuff all around you, whether it’s the giant fossil dinosaurs or the planetary rocks and the meteorites.

I always remember how excited and inspired I was at that moment in time, and so I want to pay that forward to other people — the next generation — essentially to encourage more people into a science career. That’s ultimately where I can trace it all back to.

A lot of children aren’t really aware of the range of science careers that you can have, as well as science-related careers on the peripherals of pure science, and so taking any opportunity to raise awareness of that is one of my greatest passions.

Smashing Stereotypes

The British Science Association’s Smashing Stereotypes campaign began a few years ago as a campaign to really showcase the diversity of what it means to be a scientist — so what do scientists look like? What sort of jobs do they do? The whole campaign stems from the fact that the public isn’t necessarily completely aware of this huge diversity that exists in science in terms of the jobs, but also in terms of the people that do those jobs.

The public perception of science is very much influenced by media, so comic books or films depict fictional versions of what a scientist is. Even when you see news reports on TV the types of experts you get are from a very narrow and restricted range of people.

The British Science Association has been running the campaign for a few years now, adding more scientists every year. There are people of different genders and there’s a huge mix of ethnicities.

I’m a disabled scientist myself, so the campaign is showing the public that scientists come from all parts of society. We’re not all in lab coats and wearing glasses either. They’re challenging that image of the ‘mad’ scientist like Doc Brown from Back to the Future — you don’t have to be an old white man with crazy hair to be a scientist.

Collaboration is key and no one person has a monopoly on the best ideas

More recently, science has become increasingly collaborative. When I was starting out in my science degree, and maybe even my doing my PhD, I was actually working in quite a solitary sort of way. I had my little experiments I was doing, and I was being supervised by other researchers, but I wasn’t really collaborating or working with anyone else.

Whereas, fast forward 14 or 15 years and science by its very nature requires collaboration with people from different countries, and people with different domain expertise as well. So, whenever you’ve got a problem, if you’ve got a really diverse team (with diversity in terms of the actual individuals as well as their domain expertise), you’re casting your net wider to try and find that innovative solution to get you over your problem.

Even though I work in a software engineering area, sometimes we’ve had solutions to the problems we’re working on that have been put forward by a philosopher or a social scientist. These aren’t people that are experts at software engineering, but the way that people from different domains think about problems or tackle them in a different way, and the collective experience that diverse range of people bring can benefit any project, so I think it is the way forward to have diverse and interdisciplinary teams, certainly in science.

In the open-source community anyone who wants to join in contributes their endeavours to that piece of software, whether they formally are paid to work on that piece of software or not. For example, members of the public could join our software project and contribute to help move the software forward.

Bringing people together to celebrate women in science

Even though over the last 40 or 50 years there’s been an increasing number of women and girls entering a science career, the reality is that women are still underrepresented, particularly in domains like engineering or computer science. Having a designated day where you can celebrate the women in those areas, particularly in those in high-achieving or in leadership roles in scientific disciplines means you can use that as a platform to raise awareness.

We need to be inspiring the next generation, continuing that throughput and increasing the number of girls picking science careers. The British Science Association is very active on social media and they will have a big thread where they’ll tag all the women in campaigns like Smashing Stereotypes.

Post-pandemic, it’s a different sort of environment now, and also because I’ve got a physical disability, it’s more difficult for me to get about to schools or events, so social media is all the more important.

Making academic life more accessible for disabled people

There’s been a lot of work over the past couple of decades about trying to reach gender equality within higher education, as well as different disciplines.

I’m fortunate to work in health science, which has good gender representation among researchers and senior academic staff that are leading institutions as well. However, I acquired disability nine years ago, so I’m an ambulatory wheelchair user, and when that happened it became really clear straight away that my career, my personal and social life generally pre-disability was very different from what is ‘normal’ for me now.

One of the things is that in academia we’ve got a really low number of disabled staff compared to other sectors. In higher education, I think the national statistics are that about 3-4% of research and academic staff identify as being disabled, but nationally, our undergraduate intake is that 20% of undergraduates identify as being disabled.

You have to question why there is an underrepresentation of disabled people in academic careers and what can we do to change this? Clearly, there’s a good proportion of undergraduates identifying as disabled so how can we convince them to pursue a career in academia, whether it’s science or not?

I have a strong interest in this area and trying to find strategies to do that, but disability brings its own barriers and issues. Good employers in good organisations are very proactive in addressing these barriers so they’re not even there when a student decides to pursue a career in academia.

I wasn’t aware of it until I actually became disabled myself, even though I’ve got disabled family members, but I hadn’t really fully appreciated the challenges that you have when you’re just trying to do anything really, as well as when you’re trying to build a career. I was really lucky because I had started to establish my career — I’d already had a few years of doing research post-PhD before I became disabled — so that is an advantage, but it’s much more difficult if you haven’t yet established yourself.

Putting down roots

On a personal note, my social media reminded me that it was 14 years ago today that I got my first ever job offer after my PhD, so that’s when officially my career began.

Throughout that time, I’ve always been on short-term or fixed-term contracts and not in a permanent post, but I’m due to start my first tenure track fellowship shortly, so I’m hoping that at some point over the next five years I will meet the necessary criteria to be given a tenured post here at the University of Liverpool.

It’ll be really nice to be able to settle down somewhere, because that is one of the challenges of being an academic researcher — it’s a bit of a nomadic lifestyle. You move city, and sometimes even country, every few years for work, but the older you get, the harder it can be. Being disabled makes it really hard to move every three to four years, and I feel like I would like to put down some roots, settle down and stay in one place. I’m looking forward to that.

I have also recently taken over as lead of the DataSHIELD research project. I’ve worked on this project for about ten years now and seeing this evolve from a solitary academic research project to full-blown international community is exciting. Maybe in five years’ time it might be something completely different, but hopefully we will still be producing some great science out of it.

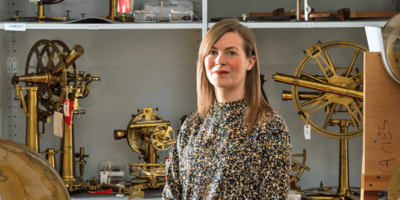

Main image: Becca visiting Google campus, Mountain View, California. Image credit — © Becca Wilson