Dr. Emma Sceats is chief executive officer of Oxford University spin out company, CN Bio Innovations, having joined in 2010 as commercial manager to spearhead the organisation’s sales, marketing and business development activities, before becoming CEO in January 2016. Emma has developed sales and partnering initiatives with major pharmaceutical organisations and overseen academic research and licensing programmes, including with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) that have led to the development of the company’s leading technologies and intellectual property. Today the company has developed an innovation to manufacture ‘human organs-on-chips’ which serve as non-animal alternatives in drug discovery and research.

“…I realised that to get to the next stages of my career I needed to start setting the agenda: I’d see an opportunity to partner with a company or a funding call and make a proposal. It’s about being proactive and putting that proposal in front of your superiors. That’s how I became CEO…”

My career in science and innovation

I’m currently CEO of CN Bio Innovations, a company in the UK that’s developing human organ-on-chip technology as alternatives to animal testing in research. We work at the interface of biology and engineering, but in fact I trained as a chemist, so after degrees at the University of Bristol and Massachusetts Institute of Technology I did a doctorate at Oxford, in chemistry again.

After that I joined the technology licensing office at the University of Oxford, now called Oxford University Innovation. As licensing manager I was involved in protecting intellectual property that had originated from research conducted at the university, licensing that to companies who would develop it into products or services, as well as getting translational funding into the university to support the next stages of technology development or medical research, and also the formation of spin out companies.

I want to do that!

I joined by current company, CN Bio Innovations, from the licensing office. I’d been transferring technologies from the university into small companies and I thought, “I want to do that!” I became CEO of the company in January of this year.

There are definitely two things that made me want to work in science; first of all I had an absolutely fantastic chemistry teacher in school – a lady called Miss Braham. I was at a girls’ school and I loved chemistry in particular as a result of the classes I took with her. I was also fortunate to do a year in industry during my undergraduate degree. I spent a year working at DuPont’s Central Research Facility in Wilmington, Delaware and it was an amazing experience. I loved the science, I loved the people. I thought: “I’m at home here. Fabulous people, brilliant science.”

Being a CEO in a smaller company: Hands on approach required

In my role I find myself trying to strike the right balance between the amount of time I spend with people outside of my company – it’s quite an outward facing role – but also making sure that within my company people are feeling supported, engaged, motivated and clear about what their priorities are. It’s important to strike a balance between internal and external.

In the last week I’ve talked with a couple of US companies who were interested to use our organs-on-chips – so technical and commercial discussions with those organisations. I’ve been working on a manuscript that I’m going to publish with our chief technology officer about our research and technologies, which will go into a scientific journal. I’ve had meetings and phone calls with investors. I’ve spent time updating members of my board about the company’s progress.

I’ve reviewed intellectual property arising from our internal research, but also looking at new IP that we might want to license from other organisations. We’re also hiring, so I’ve been involved in aspects of that – so talking to recruiters or looking at job descriptions. It’s really varied and that’s just the last week! There’s been no international travel over the last week and that makes a change.

My role is changing at the moment as we grow. Being a CEO of a smaller company you have to be quite hands on with things people wouldn’t always expect you to be hands on about, because we don’t have an HR department, we don’t have a full time finance department, so you find yourself doing quite a lot of different things, but that’s changing as we recruit people who are taking on some of these responsibilities.

Tissue engineering and human organs-on-chips

Around twenty years ago, tissue engineers were really excited at the idea that new organs could be built in a lab as an alternative to human donation for patients who were suffering from organ failure. Sadly there’s lot of people who urgently require a new kidney or liver transplant but the number of successful donations that take place is heavily dependent on people being willing to donate organs after their death, or sometimes as living donors. It’s also about matching tissue type too.

A-ha!

So tissue engineers thought: “A-ha!” We’ll build replacement organs for people and this will be a massive service to science and healthcare. It turned out that it was an unbelievably difficult thing to do – the biology is phenomenally complex.

Developing cells that can populate a whole human liver for instance is an incredibly daunting scientific task, but Professor Linda Griffith, an engineer at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who developed the technologies that we base our products on said: “Maybe we don’t need to develop a whole new human organ? Lots of people suffer from organ failure because they took a medicine that turned out to have a side effect that affected them specifically – certain patients respond badly to certain medication. Maybe we could develop miniature models of organs so that drug companies and pharmaceutical researchers can develop better medicines that don’t cause these side effects?”

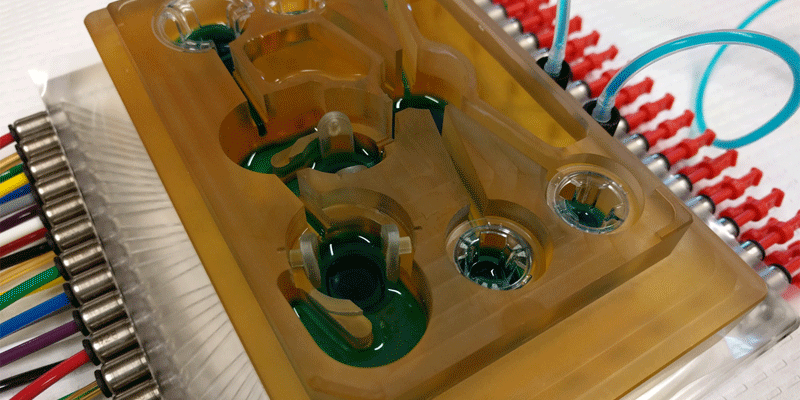

So Professor Griffith and her team built devices that enabled human liver cells to reform into tissues that resembled the architecture of the liver. The devices also allowed tiny volumes of liquid to be flowed past these cells to mimic the flow of the blood through tissues. Blood provides oxygen and nutrients to tissues to help them grow. Using these microfluidic devices they started to work with pharmaceutical companies to help them understand if a new medicine might be toxic to the liver. CN Bio has more recently used these microfluidic devices to identify medicines that could cure hepatitis B and other liver diseases.

Women in Innovation funding

In my experience there are huge numbers of very talented women going into biological and life sciences degree courses, in much greater numbers than the engineering subjects. Many of them are joining companies who are then developing new medicines, devices, products, software etc., but sadly, relatively few of these women are leading the charge to raise research funding from organisations like Innovate UK or other big medical research sponsors and charities like the Medical Research Council or the Wellcome Trust. I think typically under 20% of applicants are women.

Innovate UK is highlighting some women who have been successful at this and supporting the next generation of women innovators and it’s been a privilege to be a part of that scheme. I’ve been asked about being a role model and it’s funny because if you’re running a company you’re focusing on taking your company to the next stage – you’re not sat back thinking: “I’m a role model now!” Far from it.

I’m just working hard to keep the company running and growing! I think that’s what women do – they just keep their heads down and try to progress the business. It’s only recently that I’ve thought that if I can be a role model to other people and they want to hear what I’ve done, then great!

Career challenges for women in scientific research

One of the things that can be a challenge for women in science careers, particularly if there is an expectation around a higher degree being important is that it compresses timeframes. If you’ve spent a number of years studying, perhaps into your mid to late twenties, having done research and degree courses and Ph.Ds, then for some women that coincides with the time they are thinking about starting a family.

I had reached quite a senior level in my company, working directly with the CEO when I went on maternity leave, and in a small company where there were only ten of us I was 10% of the workforce. I appreciate that my situation is not one that everybody is lucky enough to be in – I was already senior and the chairman of the organisation is a woman who has children of her own. She and all of the board were very supportive of me going away and coming back to work, and I was able to do that flexibly. I was back at work in under four months after I had my little girl, but again, that doesn’t work for everybody.

It’s difficult for women when the end of study coincides with wanting to accelerate through their career path. Lots of families are trying to juggle two jobs too. It’s a challenge.

Being clear about my value to the company

I was very fortunate. By the time I went on maternity leave most of the key relationships with pharmaceutical companies were ones I had developed. We license intellectual property from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and I was the main conduit for that relationship.

Some key aspects of our company are ones that I had been primarily responsible for. The company was very clear about my value to them. That wasn’t out of me positioning myself in that way. I did those things because that was what needed doing, and having successfully delivered them I reached a point of being very valuable to the company.

Also, because I plan most of the outbound activities I largely set the agenda. I had to do things to meet the board agreed objectives for key milestones, but after that I was able to say: “I think we need to go to the US this week.” I was in control of a lot of aspects, but I know that a lot of women aren’t in the position of being in control of their timetable, which does introduce pressures along the way.

In the larger company that I left to join my current organisation, I could have taken a year’s maternity leave and that would have been paid, but I knew what the financials of our company were so I knew this wasn’t on the agenda. There’s pros and cons.

In a small company there has to be a lot of flexibility in both directions. Sometimes I do need to get on a plane at the weekend or be away for two weeks, but because I do that I make sure that I can go to my daughter’s parents evening. It work both ways. Luckily, nobody is more demanding of me than me, so normally the pace that’s fastest is the one I set for myself!

Realising the point in your career when it’s time to set the agenda

A lot of people, maybe women in particular but it is also true of men, think that having a job is going to be like being at school, and that you’re going to be set homework, and you’re going to do your homework, and you’re going to know what the deadline is, and you’ll hand it in and you’ll get an ‘A’ and next year you’ll get a promotion, and that’s how it works.

Something that I’ve understood for myself is that when you get to a certain point in your career and you realise that you’re going to have to be the one to set the homework. I don’t think it’s an exclusively female trait to not necessarily understand that this needs doing, but men are sometimes perhaps a little more forward – just making a proposal, taking the initiative – not because women don’t have the initiative but they don’t feel so confident to put themselves forward.

Becoming CEO

At some point I realised that to get to the next stages of my career I needed to start setting the agenda: I’d see an opportunity to partner with a company or a funding call and make a proposal. It’s about being proactive and putting that proposal in front of your superiors.

That’s how I became CEO. I said: “I think in order to address certain issues in the market we need to look at bringing some new technologies into our company.” So my colleague Dr. David Hughes (now the company’s CTO – Chief Technology Officer) and I went off and evaluated 15 different technologies and we came back with a plan of which ones we thought we should take a closer look at. This wasn’t because somebody had told us to. It was what we thought should be done.

For me, that is where I see the people that really get on in their careers. They understand when it’s appropriate for them to start playing more of a role in setting the agenda and being proactive and coming up with proposals. If you work for somebody who’s open-minded, who’s not going to love that?

STEM subjects: Nobody had ever told me I was any good at maths before

What I see a lot with girls in STEM subjects, and I know from personal experience, is that often it’s about confidence. It’s not that a female student may be less able in a subject, they might be less aware or less confident of their abilities. I remember doing A-levels and school at doing maths – I was absolutely convinced that I’d only just be able to scrape a ‘C’ and if I did it would be marvellous.

Learning to learn

My little girl has just started school where a big focus is on helping the children have a great mindset towards learning. It’s important for children (and adults!) to understand that sometimes study is really hard, so having the confidence just to carry on believing you will get to a point where you ‘get it’ is really important. Anything that allows young girls to be more confident of their abilities helps then it builds their resilience where they inevitably get to the point where they think: “Oh, this is a bit hard. How am I going to work through this?”

I still have to do that every day as the science I work with is often out of my field. It’s fantastic to learn a new subject. If you know how to learn I believe that you’re capable of learning anything. If you have the right approach to learning, and you’re capable of helping yourself to learn and you’re capable of drawing on other resources, you’re in a great position.

People should understand that as you go into the workplace now you’re constantly having to learn new things. I’ve trained as a chemist but I run a company that does engineering, bioengineering, virology, biology, cell biology, molecular biology and immunology. I work with so many different types of experts. If you’re not afraid of learning and it’s something you enjoy then it’s a fantastic career to be in.

Human organs-on-chips: Getting exciting technologies out there

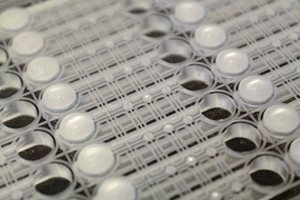

One of the things we’re working on is the next generation of human organs-on-chips. There’s lots of exciting technologies to come out of universities that don’t have the impact they ought to because important things that are going to be crucial for technologies to be successfully adopted and used by people in their research are not addressed. So we’re working really hard in our next generation of technology to develop manufacturing processes that mean we can reliably mass manufacture our products, and make them much more widely available.

There’s so much important research that is enabled by our human organs-on-chips but CN Bio couldn’t possibly do all of it on our own and so we need to get these technologies into the hands of a wider group of people. We’re working to make our products and instruments widely applicable and widely available for research across a broad range of disciplines.

https://www.facebook.com/CNBioInnovations/