Charles Gray is currently working towards her Ph.D. theoretical meta-analysis and lecturing at La Trobe University in Bundoora, Victoria, Australia. She spent a decade working in music and the arts before changing career to pursue her love of maths. She is currently touring Australian towns and cities on an Australian Mathematical Sciences programme called CHOOSEMATHS, which aims to encourage more girls to keep studying maths.

“…I feel it’s my duty to share how surprisingly fun mathematics is…”

Charles, please can to you tell us about your career to date and what made you want to work in maths?

Choosing music was an act of self-healing. I missed most of high school due to homelessness. I always felt drawn to mathematics, but I couldn’t see what I could do with it. Music was a balm for my soul, after a traumatic adolescence. I started with a jazz certificate of performance, and then undertook a Bachelor of Music majoring in musicology (the theory of music), as well as an arts degree in film theory. It felt natural to write a thesis in film music.

Through my music studies, I was introduced to the contributions of composers such as J.S. Bach to how we write melody, and in particular melody against melody (counterpoint). The axioms of this theory fascinated me.

When you analyse melodies, especially iconic melodies like Over the Rainbow, you find they still follow the paradigms established in the 17th century. Rules like if you leap, you must step in the opposite direction. There are a lot of numbers, too. You may have a melodic second or fourth, but not a harmonic second or fourth in species counterpoint.

Unfortunately, there aren’t any jobs in seventeenth century counterpoint. So, I taught piano and worked as a piano player for hire for almost twenty years. I did try to find other work, but found that my degrees were not valued. I also wanted to do something that was more like the theory I’d been attracted to. So, for the last seven years I supported myself with music, whilst studying mathematics.

It is in mathematics that I’ve found a world akin to that of music theory, but so much analytically richer than I had ever hoped. I undertook a bridging course for people who missed high school, went straight into an undergraduate degree in mathematics, honours in abstract algebra, and now a Ph.D. in theoretical meta-analysis.

What does your role at La Trobe University involve on a day to day basis?

A typical day for me is a bit hectic. I’m an early bird. Since I’ve been working and studying for so many years, the only time I could study was in the morning. I get up at 5am so that I get to my office by 7.30am. I usually plan my day, and take a moment to reflect on my research before my day gets filled with student consultations, meetings, and all the bustle of a busy department.

For my research, it’s really very split between theory and computation. So, some mornings I spend time at the whiteboard cursing equations I haven’t quite got my head around. I’m always learning new theory, and even though its challenging, it’s always fun.

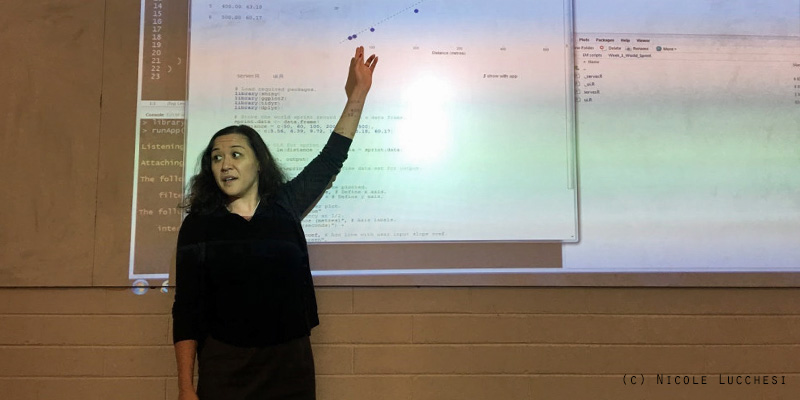

The other side of statistical research is programming. I write simulations and test algorithms. A skill I like to develop on the side is data visualisation and management, which I find surprisingly soothing after all that tricky maths.

I teach a lot, as well, lecturing in mathematics and statistical modelling. So, there are lectures to write, tutorials to put together and so forth. Students pop in randomly all the time, too. I’m also involved in a lot of societies. I’m very active with the Statistical Society of Australia, organising speakers and conferences. My afternoons are usually dominated with these non-research commitments.

Most people have the perception that maths is about doing long sums in dreary classrooms. What would you say to change their minds and challenge the stereotypes?

Hahaha, this reminds me of how I have sometimes felt like I wish I could lend my ears to someone so that they could hear music the way they hear music. Now I feel it’s my duty to share how surprisingly fun mathematics is.

My fourth-year thesis was in abstract algebra. Most of my work in this revolved around these beautiful mathematical structures like this. So, I spent a lot of time drawing pictures. There were more numbers in my page numbers than there were in the thesis, and there were absolutely no boring calculations.

Pure mathematics is all about elegant logical arguments, as well as looking for challenges that infinity or zero or nothing (the null set) might introduce. It was everything I loved about music theory and then some.

What is people’s reaction when you tell them you transitioned from music into maths and what was the hardest part about making a change?

At first people scoffed at me. People seemed to feel compelled to tell me it was a silly decision to make, and that I’d made my bed in my twenties, as it were, so I now I had to run with the career I’d already begun. People do not commonly associate music with high analytical intelligence, so I came up against a lot of scepticism.

As I progressed in my studies that scepticism began to fall away. It is very, very strange to suddenly (in my mid-thirties) be perceived as intelligent. I find people treat me the mathematics lecturer very differently than the me the pianist.

The hardest part of the transition was supporting myself. I worked through the degree, sometimes up to four jobs. I got up between 4 and 5am each day to study and only took one or two days off a month. The hours were brutal. But it wasn’t really that the hours were hard, but the loneliness of going through something like that alone I found most difficult. There were times when it felt as if no one understood how tired I was, and what a barrier that was to clear mathematical thinking.

Maths has a reputation as one of the most male dominated subject areas. What sort of support did you receive from colleagues and why are groups like Women in STEMM Australia so important?

I genuinely believe in advocacy for women in mathematics. I’m a student affiliate with Women in STEMM Australia, treasurer of Supporting Women in Science, and on the organising committee of R-Ladies Melbourne (for ladies who code in the programming language R). I believe we’re under-represented in STEMM fields, and I could reel off all sorts of statistics or go on about how many times I’ve been the only woman in the room in a seminar or so forth.

But that wouldn’t be admitting the primary reason I seek these groups out, and it’s entirely selfish. I was starved for the company of women, as well as needing to surround myself with role models I can relate to.

I like women, I like spending time with women. Men are great, too, and talking shop with everyone is great, but I don’t have to put in a special effort to find men in my field to talk maths with. Since I became involved in these groups I’ve felt far more connected with women at all levels of my discipline, and am less lonely for it.

Terrific to see PhD students @cantabile & Amanda Woon connecting with our wonderful @WomenSciAUST Ambassador @lkw_sci #IWD2017 #womeninSTEMM pic.twitter.com/XN7klz4d4x

— Dr Marguerite Galea (@MVEG001) 8 March 2017

You’re currently ‘on tour’ with CHOOSEMATHS. Please can to tell us about this?

CHOOSEMATHS is a multi-pronged initiative of the Australian Mathematical Sciences Institute, whose primary purpose is to encourage young people to study mathematics, particularly women. The motivation for this is that majority of the jobs of tomorrow will require mathematics, but students are not choosing to study mathematics. There’s outreach professional development with teachers, scholarships, and more. We’re currently travelling the country speaking to high school students as part of the careers awareness campaign.

The problems of today and tomorrow cannot be solved without mathematics and statistics. From climate change, to rising inequality, to cancer, to the housing bubbles occurring all over the world, none of these problems will be solved without the use of mathematics. This is the message I’m sharing with students this week; that they can use mathematics to save the world.

Why is a growth mindset so important when you’re studying a subject like maths?

Ah, now that is a fantastic question. If there is one thing I’ve truly learnt from my academic career in mathematics is that the idea that you’re either “good at” maths or not is entirely false. Mathematics is not an innate skill, it is learnt.

If I had to choose skills to succeed in mathematics I would choose first humility, second curiosity, and intelligence only comes in third place. Humility, so that you are not too afraid to ask why, curiosity so that you feel compelled to ask why, and intelligence (to a lesser extent than most think) to understand why.

I’ve seen a lot of people smarter than I am drop away from mathematics because they believed they were good at it, so that when it got hard they found it crushing. Of course, it’s hard at times, but it’s also so fun. The harder it is, the bigger the sense of achievement when you get somewhere with it.

What is coming up next for you and your work?

I’ve got a series of conferences that will serve as deadlines by which I need to finish research papers over the next couple of years. I’m co-writing a subject for our new Masters course in data science as well. Broadly speaking, I want to transition into being a careful and competent statistician who can solve problems in a broad array of fields.

https://www.linkedin.com/in/charles-gray-48b93724/

Johann Sebastian Bach image credit: Elias Gottlob Haussmann [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons