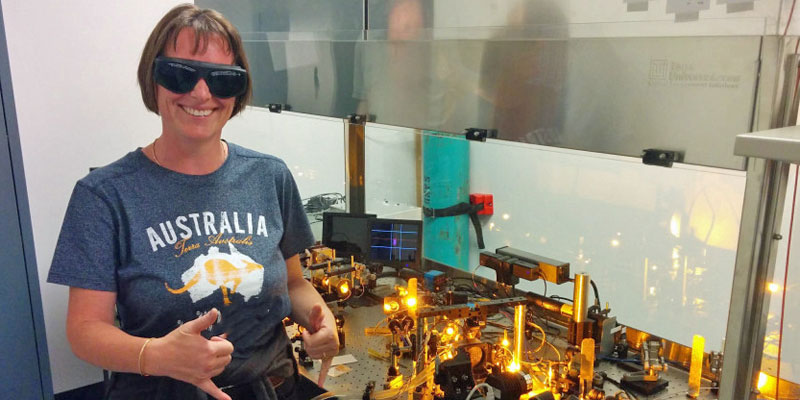

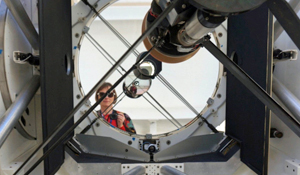

Professor Céline d’Orgeville is a professor and instrument scientist at the Australian National University Research School of Astronomy and Astrophysics, where she has also recently been appointed as deputy director of the Australian National University Advanced Instrumentation and Technology Centre. Céline leads teams designing laser and optical instrumentation systems for ground-based astronomical telescopes and she is a Fellow of the International Society for Optics and Photonics (SPIE), as well as the Astronomical Society of Australia.

“Space is the next frontier and, unfortunately, humans have a tendency of exploring in a messy and polluting way when they start out. However, there is a growing consciousness and awareness of the fact that we really need to protect the space environment, because this is a shared resource for all of humanity.”

Je suis ingénieure

I was educated in France and I pursued maths and physics in high school, got the French baccalaureate, then went into higher education studies with something that’s very specific to France called “classes préparatoires”, which means you’re preparing for entrance exams to top tier engineering schools.

I then went into optical engineering studies, via a three-year engineering course that delivers the equivalent to a master’s level. I now have a couple of master’s degrees, one in optical engineering and one in optics and photonics, with specialisation in laser physics and non-linear optics.

My role today day-to-day

I spend a bit of my time doing research and thinking about how I can apply my research, which is about lasers used in astronomy and space instrumentation.

Discussing these ideas with my postdocs and my students, I also spend quite a bit of time writing proposals to seek funding in order to be able to actually conduct that research, and be supported. I also take part in quite a few management activities, notably at the Advanced Instrumentation Technology Centre, where I work at the Australian National University in Canberra as deputy director.

Impacts of COVID-19

When Australia went into lockdown just over a year ago, we all had to move from offices to working from home. We did that for about a couple of months and then there was a progressive return to work for people who had to do it, or who wanted to do it, but the workplace was flexible enough that you could choose where to work. Since then, I’ve mostly been working from home, but now I’m transitioning back to working half from home and the office.

The changes impacted on our work. I had an experiment that was going to take place at the Mount Stromlo Observatory near Canberra, where my workspace is located. The telescope developed a malfunction that had to be repaired, but it took forever just to get all the components so the repair could take place, so things were delayed by about a year in total.

Cleaning up space junk

We’re sending more and more stuff to space – there are a lot of large programmes now, for instance, by communication companies sending CubeSats to deploy Internet globally, to serve places where there’s no fibre or other connectivity. That’s great for the people who live in these places, of course, but it means a lot more stuff in space.

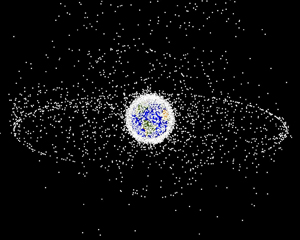

We define space junk as all the hardware that humans have sent to space that is not used anymore. It might be different satellites or parts of rocket bodies, or, more problematically, pieces of debris and hardware that collided, and that nobody could do anything about that have, in turn, created yet more debris.

There’s a number of large pieces that are being monitored via radar, or LIDAR, so we know where they are, and we can track them. But there’s a lot more pieces of debris that are too small to be seen. This is what causes the most concern because they could collide with active satellites and damage them to the point where they stop functioning, so it is a growing problem.

There’s always the risk that when these satellites are not used anymore (because they have a finite lifetime) they remain in space and become debris that can create collisions. The effect of debris colliding with debris and causing even more debris is called the Kessler Effect.

If that happens, we’re going to reach a state where there’s a cascade of collisions, and so much debris created at certain altitudes, that we can’t use that region of space for human activities anymore. That would significantly impact our current way of life, because we rely so much on space assets for our everyday activities, even though most people often don’t realise that.

CubeSats are small satellites on the order of tens of centimetres in height, width and depth. They’re like small boxes that are being sent into space. They are much cheaper for us to put together, so they’re very attractive for a lot of organisations that don’t necessarily have the budgets of NASA and other space agencies. They’re actually quite versatile and you can do a lot of things with them, like for instance, astronomy or earth observation.

In February 2018, Space X sent a Tesla Roadster car to serve as the dummy payload for the Falcon Heavy test flight and that became an artificial satellite of the sun. ‘Starman’, a mannequin dressed in a spacesuit, occupied the driver’s seat. It was sent outside of the immediate orbits around Earth, but it’s not going to break up anytime soon. Someone’s definitely going to find that car sometime in the future!

Humans are messy explorers

Space is the next frontier and, unfortunately, humans have a tendency of exploring in a messy and polluting way when they start out. However, there is a growing consciousness and awareness of the fact that we really need to protect the space environment, because this is a shared resource for all of humanity.

There are space treaties that say that nobody owns space, and we need to share this resource, so there are a lot of discussions to try to agree on how to use space. What’s the best way to do this for future missions and how to ensure that whatever we send to space can be either sent to some graveyard orbits where they won’t interfere (or at least not as much) with existing assets or bring back satellites to Earth where they can burn up upon re-entry.

Using science fact rather than science fiction

I’m excited by all the new techniques and technologies being developed to tackle the problem of space debris but what I’m doing from the ground is not really blasting debris. We’re just trying to push on the debris and move it just enough so that if a collision has been predicted it can be avoided. We don’t destroy the debris, and unfortunately, we don’t remove it, but we delay the onset of that Kessler Effect, and possible collisions that create more and more debris.

There’s techniques from the ground using lasers, which I’m excited about because I love lasers, but there’s also other techniques that are being proposed, where people plan to grab debris in space, they are sending missions, whose purpose is actually to clean up space. And there’s a lot of ideas floating around and being tested. We’re just at the very beginning of that but hopefully, we’re at a scale where cleaning space junk can become a commercial activity and we’ll get better at it.

Female representation in STEM

Looking at the STEM disciplines, in the space sector, it’s pretty much the same as every other STEM discipline where there is a lack of female representation. In engineering, it’s around 15% participation of women – it can be higher or lower, depending on the sub-discipline you’re looking at. In physics, it’s about the same – between 10% to 20%.

We could spend a whole day if we were going to discuss why this is, or what should be done about it, but let’s just say we need to encourage more girls and women to work in space, without a doubt.

Something important to remember though is that you don’t have to be working in the STEM fields to work in space, you can get involved with space by being a space lawyer or by being an entrepreneur and looking at commercialising some of the activities I was talking about. Still in STEM but outside physics and astronomy, there’s loads of other things that can be done to contribute to the space sector, like being a space biologist, for example.

Because society is not very supportive of women working in STEM disciplines it means they need to have even more drive, passion and resilience in order to make it. The women who stay around usually have to be better than the majority of the men just because they had to get past all these additional difficulties that were thrown at them.

Getting on board with space careers

Nowadays there are a lot of opportunities for kids to get involved with extracurricular activities that will bring about interest in research or engineering, so it’s a matter of getting the information. There’s a lot of programmes – internships or mentorships, or there’s obviously a lot of information online about what space is about and what you can do.

I would recommend looking into these possibilities and trying your best to get on board with these programmes, because once you are it’s just fascinating and exciting. Your interest just grows and your passion grows alongside it. Be confident because you can do it. There’s no doubt about that. It all boils down to being self-confident. Whatever other people say, just believe in yourself.

Excited for my new role

As I hinted at the very beginning of our interview, I’m just starting in a new role at the Advanced Instrumentation and Technology Centre, as the new deputy director there, so this is very exciting. I’m going to be looking beyond my research area so I’m going to learn so much more about things other people are working on in our department, and I can’t wait.

https://www.linkedin.com/in/cdorgeville

https://researchers.anu.edu.au/researchers/d-orgeville-c