Carol Storer OBE is Director of the Legal Aid Practitioners Group (LAPG), a membership and lobbying organisation for lawyers and others working in legal aid. The LAPG is committed to the provision of a legal aid system that protects all the vulnerable in society by ensuring access to justice for everyone. Prior to joining the LAPG, Carol was a solicitor and subsequently a partner at Templeton Bailey Solicitors in Greenwich before going on to join Shelter UK as Legal Services Manager.

“…I cannot emphasise how appalling the prospect is that lawyers will once again come only from rich families, because I think in the 70s, 80s – and 90s even – the law became a much more democratic profession, so more welcoming to women, members of the ethnic minorities…”

Carol, please can you tell us about your career to date and what made you want to work in the law, and in particular in legal aid?

I seem to remember at school I did quite a lot of debating and I remember writing an essay saying either I would like to be a journalist, a lawyer or an MP. I think I’ve always had a feeling that I want to do something where I felt that I’d be useful in society.

When I went to university I did Law and Politics. When I went into law college I was surrounded by people who wanted to go into the commercial world but I was only ever interested in local government or legal aid work. I started off in local government and I really enjoyed that, but I decided that rather than advising professionals within the local authority I’d rather represent the public so then I went to work in a law centre and I was hooked!

I suspect that my parents were worried when I left local government, took a pay cut and went to work in a law centre. Then took another pay cut to work in private practice. Then another to work at Shelter. I felt that when my mum came to the Palace to see me collect the OBE for services to legal aid – only then did she perhaps stop worrying about my career choices.

For those of our readers without a legal background, please can you briefly explain about the history of legal aid and why it is so important in order to ensure everybody in society has fair access to justice, regardless of their financial circumstances?

I did housing law at a law centre in the early 1980s and there was a lot of dynamism in this area, with Andrew Arden QC putting housing law on the map. There was a service where if you were within financial limits and you could prove that you were within an area of law, was much easier to do, then you would often get advice or representation.

Since the coalition Government we’ve moved away from that and there have been increasing restrictions on areas of law where legal aid is available. It’s much harder to prove you’re within the financial limits – the evidential requirements have got harder.

It’s a stunning, stunning difference. Instead of a legal aid system where you could be pretty sure that the general public understood it, if they were financially eligible it would be easy to prove they were financially eligible. If they’d suffered domestic violence, if they had a housing problem, if they had an employment problem – people understood the legal aid system. There were still shortages of lawyers and advisors.

It could be very upsetting for people if they were within the legal aid system but they still couldn’t get advice because there weren’t enough lawyers doing legal aid work, but generally it was a system that was understood. Now it’s extraordinarily complicated to understand what’s in the legal aid system.

Even where people should be in the system, for example if they’ve suffered domestic violence and want an immediate injunction, or they’ve suffered domestic violence in the last two years and they want to go to court to sort out arrangements for the children or about the home, there are evidential requirements and financial hurdles people have to overcome that mean even where, in a limited area of law, people should get legal aid, people are not getting it.

It’s been three years since LASPO (the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012 – an act changing the legal aid system and cutting the numbers entitled to legal aid) and it’s shocking the difficulties people face.

The system has come under pressure from successive governments, and most recently as a result of austerity. What are the changes and what impact is this having on vulnerable members of society?

There’s a big political point in a democracy that you should not have difficulty enforcing your rights. There’s no point having laws if they’re meaningless because you can’t enforce your rights, so when we talk about public spending cuts we have to say, “Well, what is a democracy? What is the minimum that the state should do? And I think that the state isn’t even doing the minimum at the moment. I don’t think people suffering from domestic violence are getting a fair deal. They’re not getting protection.

I think children and vulnerable people are suffering enormously in various ways. I think Parliament promised there’s be a safety net called exceptional case funding and the Government estimated there’d be about 6,000 applications per year, and in the first year 69 were granted. I think politicians thought that was a genuine safety net. It’s not a genuine safety net and there’s been a legal challenge to it.

LAPG was so concerned about the cuts to legal aid we produced a Manifesto for Legal Aid setting out what we think the Government needs to do to uphold the rule of law. We put forward very reasonable proposals so that those facing injustice can take action so we cover some areas of law which should be reinstated, making it easier for people to provide financial information so they get advice, steps to protect judicial review cases, suggestions for vulnerable groups and then we work through areas of law to suggest the basics that need to be brought back in.

If you’re looking at inefficiencies in the system, AdviceUK did work with Nottingham Council in benefits work and they looked at what is coming out of local authorities, what is coming out of the DWP [Department for Work and Pensions] that people don’t understand so they go to a local advice agency to get advice about it. It turns out that if you put a bit more thought into how you send out your decision, you can actually cut the need for advice.

At the moment there isn’t advice for initial welfare benefits work, but you have this very dynamic project looking at ways of making it easier for people to understand what was going on and cutting the need for advice at all.

Across the board there are so many ways of improving public services so that things are more streamlined. So for example by cutting legal aid for family work you are arguably increasing the cost to the court system if you have people litigating in person, because if people represent themselves it often takes longer in court, and going to court is a very expensive process. So you need the Government to analyse whether their cuts are saving money.

If for example in employment law you’ve got a double whammy of no advice on employment law under the legal aid system (unless there’s discrimination, when you can ring a phone line) and you have to pay very much increased fees for tribunals. So what you’ve got is a system where workers rights have in the past been protected because there were rights they could enforce , but now it looks like employers can get away with more and more breaching of rights because they know it is harder to challenge bad practice and for example dismissal.

In society now you’ve got people with low finances having great difficulty enforcing rights against a stronger party and that may be a woman in a family law case, or it may be an employee, or it may be someone on benefits against a Government department, or an individual seeking to judicially review the state, and I think you have to ask, in a democratic society, where you’re heading if you cannot provide protection to everyone. The law should have protection. There’s a difference between theoretical rights and rights that you can enforce. You want rights that you can enforce.

There’s a historical perception by the public that lawyers are all fat cats – how far is this the case in legal aid and what are the statistics for the number of legal aid firms that have closed in recent years?

It used to be easy to do legal aid work if you were a provider – a firm of solicitors or a charity or a law centre, or a not for profit. You used to just be able to do legal aid work as long as you had a centrally recorded number, so I think in 1990 there were about 11,000 firms doing legal aid work. Not it’s a bit hard to tell because you have the firms that do civil work and firms that do criminal work, so if you merge them and work out how many firms there are – taking away branch offices [of the same firm] and things – I think there are about 2,600, but I can’t be absolutely sure about it because it’s quite a difficult exercise to do.

So I think we’ve gone down roughly from 11,000 to 2,600. Legal aid firms don’t necessarily close down in a way that’s public. A lot of firms just simply stop doing certain types of legal aid work. So you used to have big firms doing a wide range of legal aid work. For example Fisher Meredith do very limited amounts of legal aid work, whereas less than fifteen years ago they were a major legal aid provider, but it’s no longer financially viable to do the type of work they were doing.

If you talk to organisations like Young Legal Aid Lawyers for example, the amounts people are getting are very much in line with I would have thought nurses, teachers. It’s not a huge starting salary and is doesn’t go up hugely either. And you’ve got to remember that partners in legal aid firms are funding the business. Their homes may be at risk if the firm goes under and they won’t pay themselves if there’s not enough money one month. They’ll pay tax, National Insurance, VAT and their staff before they pay themselves. I know cases of firms where the partners haven’t paid themselves for months on end. There isn’t the money.

Why do people do it? Because they’re passionate about the type of work they do, but you do have to be able to eat and to pay your way in life. It is a worry that as people are squeezed more and more you’ll gave fewer and fewer people doing legal aid work.

There’s a lot of unsociable working hours. I used to do a lot of work on homelessness. If someone comes to you at 4 o’clock in the afternoon, you may be with them until ten in the evening if you’ve got an order from the high court for them to be housed overnight. If you’ve got a family sleeping in a car you don’t turn them away. You see them immediately and you’re often feeding clients because they’ve spent hours at the homeless persons’ unit. When they finally get to you they’re exhausted, the children are exhausted, they haven’t eaten all day and you have to keep them hanging around while you’re doing their legal work and they’ve got nowhere else to go.

It is a very demanding world that people are in and they’re trying very hard to give a service. It’s often incredibly energy sapping as well as very rewarding.

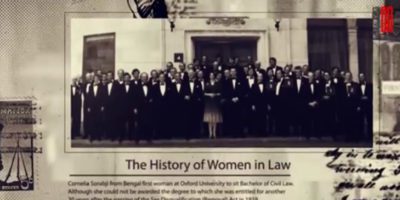

How is diversity in the profession being affected by changes in the market and how is this impacting on the ability of women and members of ethnic minorities to pursue a career in, for example, criminal law?

It’s scandalous. There’s a period in life – I qualified in the 1970s – where I was funded to go to university, I was funded to go to law college, so I started work without huge debt around my neck, and the difficulty now is if you do not come from a rich family. I cannot emphasise how appalling the prospect is that lawyers will once again come only from rich families, because I think in the 70s, 80s – and 90s even – the law became a much more democratic profession, so more welcoming to women, members of the ethnic minorities.

It’s very difficult with fees – not only university fees but then to go on and do the necessary qualifications to become a solicitor or barrister the fees are huge. It’s then very difficult to get a training contract or to get a pupillage, so unless you have money backing you up, even with a law degree that’s quite a useful thing to have, you would need a huge amount of optimism to do the further training to become a solicitor. If you haven’t got money in your family, then many people are very worried and that’s why I think things like the Chartered Institute of Legal Executives as a way into law may prove much more popular in future.

I think it is an absolute disgrace where we are now with a lack of opportunity for people. I would also say that I think the legal aid world has been particularly welcoming of women and members of the ethnic minorities at a time when the other organisations weren’t so welcoming. When legal aid paid enough for you to run a business you could do that.

Now that it’s such a struggle to run a legal aid firm it’s obviously much less of a prospect and if you look at every consultation that’s ever been prepared by the Law Society and the Bar Council about changes cutting legal aid, they’ve highlighted how difficult it is for BAME [black, Asian and minority ethic] lawyers and for female lawyers. If you look at for example, the Junior Bar and crime, go on Twitter and see how many people are saying there will be a smaller Bar because the people with be less able to do criminal defence work in future because the money’s not there.

The LAPG runs the Legal Aid Lawyer of the Year Awards. What sort of stories do you find about lawyers going to extra mile to fight for the rights of their clients?

So people nominate their own solicitor, their barrister or colleague. Sometimes you’ve got people who have just run successfully a tremendous case which is of earth-shattering importance. They’ve taken a case up to the highest court in the country and they fought tooth and nail, even when they’ve had to challenge difficult decisions and then they win at the Court of Appeal or the Supreme Court because they have pursued their client’s case on a point of great importance and they’ve done it against the odds in the face of considerable difficulties.

So you have great stories of people who have achieved a great result, not only for their client but for a wider group of people. Sometimes that group of people is not a popular group and it takes courage to fight for groups if you are for example then disparaged in the press.

Also you just have some people who have spent a lifetime serving their clients, giving a service which is warm and friendly, but efficient. They’re serving their local communities, always available to give advice – often giving advice about not pursuing a case if it’s not a good case to pursue – but being a member of the community and someone that local community groups know they can trust to send people to.

One person put off their wedding because a trial was listed for a certain date. (Luckily the wedding did go ahead but it was delayed!) It’s almost every day now that we hear about lawyers providing food for the clients and they drive them to appointments. They do everything they can to support them and it is just great to have one night a year when you can say, “Look world, we’re not fat cats. It’s a tough old world but look what legal aid lawyers are doing.”

Lawyers are never popular but they’re fundamental to ensuring that the citizen can challenge the state and can enforce rights. They will never be popular with Government but the Government shouldn’t be attacking legal aid lawyers and should be saying, “What a fantastic job you’re doing.”

What are you working on moving forward to how can the public and other member of the legal profession show their support for legal aid?

That’s a fantastically interesting question about what the public can do. We’ve got an annual conference in Birmingham. We’ll be doing training for the profession. We were really worried about practices going under so we got some Government funding from the UK Commission for Employment and Skills to run a training programme for small / medium sized practices, help them survive and look at business planning.

So we’re very hands on helping with business survival and we’ll continue to meet with the Ministry of Justice and Legal Aid Agency to discuss what needs doing and what changes could be made. The Legal Aid Agency is introducing an IT system that we’re concerned about and we’re doing quite a lot of work on that.

Every time a consultation comes out we try to respond, but every consultation the profession has responded to, it does feel like the coalition Government and this one just goes on regardless. So I think the next deadline for a consultation is for the closure of several courts.

It’s all very well for the MoJ [Ministry of Justice] to say, “Look, we’ll close this court and people will have a court in under and hour,” but actually, public transport, hearings at ten, traffic, lack of buses in rural areas – it’s very hard to close a court to save money. We continue to work with the Law Society on this. The problem is if you don’t get to court for your hearing, all sorts of things can happen. In crime of course, a warrant can be issued for your arrest. In a civil case like housing – a possession case – if you’re not there to argue, it’s more likely a possession order will be made. It’s absolutely crucial that people can get to court.

For the public and other members of the legal profession, many people do pro bono work, people volunteer at law centres and other agencies, and that’s really important work. It’s really helpful when City firms write in support of legal aid work because it’s important in society and I would applaud the big City firms in particular who have done this in the past and worked collaboratively with law centres and legal aid practitioners on issues.

It’s really hard to engage the general public because if they’ve been to a lawyer and had help when they were in crisis they’re not going to want to talk about it, are they? They’re not going to go on telly and say, “Legal aid work is really important,” because if they got legal aid because they were facing eviction of because they were suffering domestic violence, it’s not something you go on television and you campaign about. It’s very hard for people who are often very traumatised to try and speak to say, “Legal aid has made a big difference to my life.” Winning over the public and getting the public involved is extremely difficult.

The Law Society put a lot of money into a campaign called Sound Off For Justice, fighting the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act, but people are hard to engage because a lot of people don’t use a lawyer in those circumstances who are in a position to campaign or support or talk about it because it was such as terrible time in their lives. The media always want people to tell their stories, but people don’t want to tell their stories! Legal aid helps people often at times of crisis.

Engaging the public seems to me to be a real struggle. When campaigning on legal aid issues you have to think quite outside the box about how to get your story heard. Recently Fat Rat Films did a cartoon and that was quite interesting. There’s also fantastic organisations like the Justice Alliance doing work – it’s a coalition of people from private practice and from charities, unions etc. and they do very good work on running campaigns to get the media involved.

We need to try to be a bit more innovative, but I have no easy answer there.

https://twitter.com/CarolStorerLAPG

https://www.facebook.com/legalaidpractitionersgroup

https://www.linkedin.com/company/legal-aid-practitioners-group-lapg