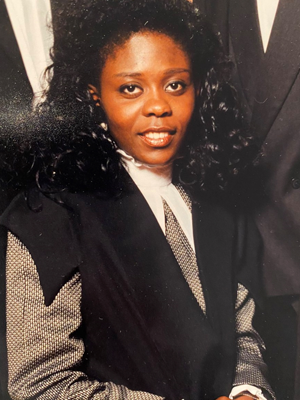

Barbara Mills QC is a barrister at 4PB, the largest family law barristers’ chambers in London and UK. She is a specialist family practitioner with an emphasis on cases involving children, and she is regularly instructed by local authorities and guardians in complex care proceedings. Barbara is co-chair of the Bar Council’s Race Working Group.

“The Bar needs to reflect the society it serves…”

Keeping busy, engaged and interested

The first half of my childhood and education was in Ghana where I attended the Ghana International School. I completed my secondary education at the Rickmansworth Masonic School where I was a boarder thanks to being awarded an assisted place.

I then completed my law degree at the University of Hull between 1986 and 1989. I returned to London and attended Bar School in 1989-90. I secured a pupillage during my Bar School year at the set where I still practice and secured my tenancy during my pupillage. All very straightforward and traditional.

I have always practised exclusively in family and in the last 20 or so focused and specialised in difficult, complex and sensitive cases concerning children. My work primarily involves high conflict cases featuring allegations of serious abuse and parental alienation representing parents often where the outcome has life-changing consequences.

I am also instructed in cases where a parent faces the prospect of a child moving to another part of the world. My practice is based in London, mainly in the Family Division and the Central Family Court. When I am not in court, I am heavily engaged in advisory work and preparing cases.

I am committed to non-court solutions and have established a successful mediation practice. I receive referrals from High Court judges, QCs and other professional colleagues.

I am a fellow of the IAFL (the International Academy of Family Lawyers) and I receive requests for urgent advice from lawyers across the world.

I have been a Recorder, part-time judge sitting at the circuit judge level, for about 10 years. I have been an arbitrator since 2016. I am a Governing Bencher at the Inner Temple (one of four Inns of Court, the professional associations for barristers in England and Wales).

I, together with Michael Edwards, edit the International Family Law Journal.

As you can see, I have a number of different strands to my work life which keep me busy, engaged and always interested in whatever I am doing at my desk. I feel very fortunate as I recap all that I do!

Adapting to COVID-19

I took Silk on 16th March 2020 – literally a week before the first lockdown. It was an interesting and challenging time. Often when one takes silk, there is the expectation that there will be a dip in the work as you transition from being a senior junior to a silk, so the world as we know it coming to such an abrupt halt, raised some fear and a worry about what my working life would be.

I need not have worried. The slowdown in work never happened. Yes, there was a downturn in court hearings as cases were initially removed from the diary and we all flapped around a bit, but this lasted no more than a couple of weeks. Within a few weeks, the family justice system began to adapt itself to telephone then hearings using various online platforms which allowed parties to see and be seen.

So, the anticipated drop in the volume of cases never happened for me. What was a huge change was only working from home. I have always been someone who reserves heavy preparation of cases to working from my study at home but there was always a reason to leave the study and commute into town: court, meetings and conferences with clients. It soon became clear to me that I needed to have a schedule for working at home that brought in proper breaks and downtime.

The temptation to keep on working was huge. I love walking and actually soon began to miss the commute into chambers. I therefore introduced a walk at the beginning and end of the working day which mimicked the commute and has been invaluable.

The best thing about working during these sometimes-odd COVID times is the rediscovery of the need to place greater emphasis on wellbeing, taking breaks and finding balance.

The Bar Council’s Race Working Group

You only have to look at the Bar Council website and the websites of most of the Inns to see that the issues around equality, diversity and inclusion have been taken seriously for a while now. However, things changed in the aftermath of a number of racially motivated events. Those events re-ignited the debate on racial disparities and inequalities that still pervade our society and the urgency for a need for action became plain and obvious.

In June 2020, the Bar Council set up its Race Working Group (RWG) and appointed Simon Regis (deputy director at the Government Legal Department), and myself to be its co-chairs. The group focus is unique in that it has representatives from all of the Bar’s stakeholders as race-based networks and initiatives. We have met roughly once a month since June 2020.

Our task falls into the following four broad areas as it affects the Black and Brown community of lawyers at the Bar:

- To establish the factors that hinder access (who gets in), retention (who stays in), progression (who gets on and grows into leadership roles) of Black barristers;

- To look at the Bar’s culture;

- To identify interventions to address the barriers faced by Black practitioners; and

- To identify the role, if any, that the Bar Council and Bar-based organisations can play in challenging systemic disadvantage faced by the Black community more widely.

Race at the Bar

On the 5th November 2021, the RWG launched its report: Race at the Bar: A Snapshot Report.

The report is the first of its kind – because of the themes and issues it covers (retention, access, culture etc.) in one report and because the research was based on an intersectional approach.

Previous studies tend to look at either gender or race, and most research does not drill into the ‘Black Asian and Minority Ethnic’ category in detail – whereas we have looked in detail at the differences between barristers from different ethnic minority backgrounds, not just one homogenous group (i.e., all Black people; all women).

The report, which focuses on the practical ways in which the Bar can begin to tackle the under representation of Black and Brown talent, also collates and presents the latest evidence on race at the Bar in one document. As such, it is extensive and this article does not purport to replace the report, and readers are encouraged to consider, disseminate, and ultimately apply its recommendations in full, wherever applicable.

The report has six key findings. These findings are:

- There is incontrovertible evidence, in quantitative and qualitative terms, that barristers from ethnic minority backgrounds and Black and Asian women, face systemic obstacles in building and progressing a sustainable and rewarding career at the Bar.

- Candidates from ethnic minority backgrounds are less likely to obtain pupillage than candidates from White backgrounds, even when controlling for educational attainment with reference to evidence such as university ranking[1], BPTC grade ad degree class.

- Black and Asian women at the Bar are four times more likely to experience bullying and harassment at work than White men[2].

- Even when factoring in practice area, work volume, region, seniority, women earn on average less than men; Black men earn less than White men; and Black and Asian women earn less than Black and Asian men, and Black women earn the least. The income differentials vary between practice area but are significant[3].

- Black and Asian barristers are under-represented in taking Silk. There are just five Black/Black British female QCs and 17 male Black/Black British QCs in England and Wales. There are 16 male and nine female Silks of Mixed ethnicity. There are 17 Asian/Asian British female QCs and 60 male Asian/Asian British QCs. This compares to 1300 White men and 286 White women[4]; and

- Black, Asian, and other ethnic minority candidates are less successful in achieving judicial appointment; rates of recommendation from eligible pool of applicants are an estimated 36%, 73% and 44% lower respectively when compared with White candidates[5].

Its key takeaways — things that we as members of the Bar can do better in ensuring we remove the systematic obstacles many barristers from ethnic minority communities face in building sustainable careers involve: (i) target setting; (ii) monitoring progress; and (iii) taking meaningful action.

Tackling inequality

The report shows the way we might tackle some of these findings by providing the Bar and its stakeholders with 23 detailed recommendations which will lead to change in all four of the areas the RWG was tasked to look at, namely the Culture of the Bar (its way of life), Access (who gets in); Retention (who stays in) and Progression (who thrives and becomes leaders)

I am keen to emphasize that people should read the whole report not just its executive summary. As a report steeped in data and supplemented by personal insights and lived experience of members of the profession, it provides incontrovertible evidence, if this is still required, that there are systemic failures within the profession.

There is no need for more deep diving in the name of further research — there is no need to search further for more information. There is even less reason to simply discuss the issue. We are in a crisis, especially in senior leadership roles and entry into the judiciary. The Bar needs to reflect the society it serves, and it doesn’t – so the time for action is now.

The importance of representing and reflecting society

If the Bar truly represents/reflects the society it serves then public trust and confidence would increase. It would also help to challenge prejudice, stereotypes and bias that exist in the justice system and society.

People from different backgrounds bring rich, new and different knowledge, ideas and experiences. If the existing structural barriers and obstacles are removed – there is a better chance for talented individuals to take the (meritocratic?) opportunity for pupillage, employment and career progression.

Inclusion initiatives at the Bar Council

At the Bar Council the following inclusion initiatives are in place:

- Tacking action and encouraging others to take action on recommendations in the Race at the Bar report (2021). Critical is support on target setting.

- Accelerator Programme (Modernising working practices at the Bar). Key elements of this programme (made up of nine discreet projects) include four projects which focus on work distribution (more equitable briefing practices). As part of this, income monitoring across chambers (by sex and race) and improving practice management support for under-represented groups more generally is a priority.

- Bullying and Harassment. With a focus on improving reporting (including via its Talk to Spot platform) and taking action on any reports of inappropriate behaviours (including judicial bullying); Bar Council is also working on a campaign to create a more supportive culture at the Bar

- Courts Access. Working to improve access to courts for barristers with disabilities.

- Bar Council Leadership Programme (a programme that aims to develop and support more diverse Bar leaders).

Coming up next

In our view, we should be focusing our attention on seven key areas:

- Mentoring opportunities.

- The selection criteria for who gets pupillage.

- The recruitment experiences of candidates both during interview and afterwards.

- Access to the quality work and then ensuring that barristers from ethnic minority backgrounds are being properly remunerated for the work they do.

- Representation of ethnic minorities at Silk level.

- Representation of ethnic minorities on Panels and at the judicial level.

- A change in the culture at the Bar. This last point is the most crucial in some respects because you change that and other things will start falling more naturally into place.

The RWG believes that the Bar’s culture is dynamic and can evolve, and so that part of achieving change is:

- Through improving access, retention and progression;

- Improving knowledge and understanding. The report recommends this is achieved through training for all barristers on equality, diversity, and race awareness, with enhanced training being taken for any barrister taking on a leadership role (in their chambers, SBA/Circuits, Silk or a Judicial appointment);

- Providing a more supportive work environment. This includes a zero-tolerance approach to bullying, harassment or discrimination with effective sanctions, and better support from a wellbeing perspective, such as forums or networks where collective experiences can be shared; and

- About the narrative around leadership, representation, and visibility. Only through a targeted and strategic approach being adopted to encourage Black and ethnic minority talent to stand and take up leadership positions can we ensure that the culture of the Bar truly changes at the top.

We intend to engage with stakeholders with a view to reporting on progress in the autumn of 2022.

On a personal note, and COVID rules permitting, I am looking forward to a few more walking holidays and the chance to explore England’s fabulous coastline.

[1] BSB Diversity Data 2020

[2] Barristers Working Lives 2021

[3] BMIF, Criminal Legal Aid Review Report, BSB Income at the Bar report November 2020

[4] QCA; Bar Council’s CRM data (October 2021)

[5] Judicial Diversity Statistics 2021

Reference links

- https://www.linkedin.com/in/barbara-mills-qc-5ab60113

- https://www.4pb.com/barrister-profile/barbara-mills/

- https://twitter.com/bmillsbarrister

- https://www.barcouncil.org.uk/support-for-barristers/equality-diversity-and-inclusion/race.html

- https://twitter.com/thebarcouncil

- https://www.linkedin.com/company/general-council-of-the-bar/