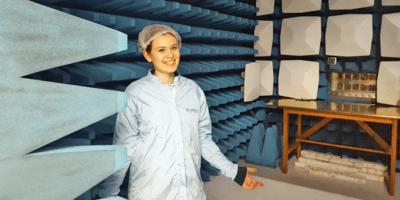

Dr Heidi Thiemann is a co-founder of the Space Skills Alliance, a think-tank made up of experts in space skills, training, and recruitment aiming to improve the way organisations in the space sector work together to address common skills challenges. The Space Skills Alliance helps the policy-making process in the space sector by publishing accessible data and reports that are as rigorous as academic research. Heidi and her colleagues provide expert advice to organisations looking to improve their skills pipelines, not only recommending solutions, but also helping to institutionalise more effective processes.

“It’s important for us to look outside the space sector too because we’re guilty as a sector of relying very much on space being incredibly inspiring to attract new talent.”

Wanting to be an astronaut was my thing as a kid

I’ve always had an interest in space and it’s always been something that’s made me feel really excited and inspired. Some of my earliest memories of space come from watching the solar eclipse in 1999 and having a poster of the Beagle 2 Mars lander on my wall when I was young.

When I was starting secondary school, I realised that I wanted to work in space. Like every kid, you choose something completely unattainable and ridiculous, so wanting to be an astronaut was my thing. I thought: “Even if I don’t actually get to become an astronaut, the path to it is a really interesting one.”

Throwing myself into the space race

When I was a teenager, I went to Space School UK and was lucky to be involved in activities like Airbus taking girls in STEM to the Farnborough Air Show, so I had some really positive interactions. So, by the time I was choosing what to do at university, I was very much set on space and I went to the University of Leicester to study physics with space science and technology, which I loved.

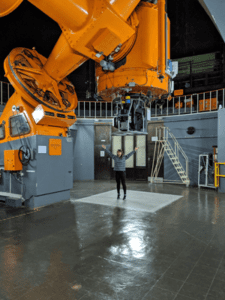

I got to do some exciting projects. One of these was with Airbus again, looking at space debris, and another observing exoplanets. When it came to the end of my degree, I didn’t really know what I wanted to do, but I knew I wanted it to be in space, so I applied for lots of different roles, and the first one I landed was a PhD.

After university, I was lucky enough to do a PhD in astrophysics at the Open University. I think most people perceive the Open University to be an undergraduate distance learning institution but there’s actually a research campus in Milton Keynes, which is where I worked for four years, doing my PhD.

I was focused on researching a particular type of star called ‘variable stars’. These are stars that change in brightness for a physical reason, and you can monitor that brightness and work out what’s going on inside the star itself. The ones I was studying should eventually collide and form stunning stellar explosions, but that’s 20,000 years in the future!

Beyond my PhD I wasn’t quite sure what I wanted to do. It was the middle of the pandemic, so it was quite an odd time. A friend recommended a job to me that was all about setting up space education and training, working in Cornwall, and I enjoyed spending a year and a half working at Truro College. In this role, I worked with local space companies in Cornwall, developing their space apprenticeship programme and setting up space education and training.

Space Skills Alliance remit

The work I’ve been doing on the Space Skills Alliance, alongside my co-founder, Joseph Dudley, has instigated by a lot of conversations and questions like what skills are in the UK space industry? What are the gaps? How do we quantify them? What do we do with the data? How do we change policy to make sure that we’re getting the best sort of education and training that we can for the space sector?

We set up the Space Skills Alliance to try and tackle that skills gap and answer some of those questions. We’re a think tank/consultancy, but I think it’s also fair to say that we are massive data nerds and we love doing bits of research, and sharing the resulting findings. Wherever possible we take our own primary research and make it public so other people can use it for policy-making decisions, or in their own workplace.

Telling stories backed by data

My role varies so much day-to-day. This morning, I’ve been at a conference talking about space and skills, but I’ve also been working on reports for a space cluster, looking at how they can use their existing facilities to best educate people in the region. Next week, we’re launching a space skills survey and I’m at other conferences which are focused on the space industry and the skills it needs moving forward.

We love data visualisation, and we love spending time trying to make the graphs look as good as possible. For us, it’s not just about putting data out there and hoping that someone understands it. It’s about telling a story with each graph.

Space Census

We ran the first Space Census in 2020. The work we did to set this up came about partly due to Dr Craig Brown’s role as a diversity and inclusion champion on the Space Skills Advisory Panel. When we first sat down and chatted with Craig about the skills issue there was lots of data about the economic size and health of the space industry, and lots of data about the companies, but it was all cold, hard statistics, and there was no data about the people working in the space industry, why they joined, and what inspired them.

We didn’t know the demographic breakdown. We didn’t know whether they were actually even enjoying their job or how much they were paid. In collaboration with the Space Skills Advisory Panel, and with Craig as the diversity and inclusion champion, we thought: “Let’s do this — let’s collect the first data on the demographics of the UK space sector.”

We launched in 2020 in the middle of the pandemic, so trying to collect that data held its own challenges, but it was a really interesting and important exercise. We had to decide what did we want to ask people about themselves, and as importantly, how did we want to ask them, because it’s quite a personal survey when you are being asked:

- “Where do you work?”

- “What do you do?”

- “Do you enjoy your job?”

- “How much are you paid?”

- “Have you faced any sort of discrimination in your workplace?”

There’s a lot of quite sensitive information we were asking about, but we were really pleased that so many people were incredibly receptive to it. (We had about 1500 people respond, which is about 5% of the space workforce in the UK.)

From the data, we’ve pulled out detailed reports on the demographics overall and also data on a broad range of subjects, including the experiences of women, the first baselining of pay in the UK space sector, and also why people join the space sector.

Exploring the experiences of women in the space sector

One of the areas where there was a clear specific need following on from the research was around the experiences of women. When we were dealing with demographic data, we realised early on that it is very sensitive and if you ‘cut’ the data from the groups too small, you didn’t want to end up identifying anyone individually.

Luckily though we had enough women respond that we could do this group analysis. Women made up 29% of the sector overall (in industry it’s about 22%, in academia it’s about 35%), and the incoming workforce appears to be much more evenly split. So, if we can retain the younger women coming into the workforce, the workforce will be a lot more evenly split in the future, which is quite a positive message.

There were some negative things that came out, for example around women’s experience of gender discrimination. I think that’s possibly not surprising to people, but actually having the statistics on women’s lived experience means that we can act on them and actually say to employers: “Look, this is happening and it isn’t a good thing,” and take actions to fix it.

Creating opportunities for flexibility

There are still things we want to find out about the sector. For example, in the Space Sector Skills Survey we’ve just launched, one of the questions we are asking is about working remotely, in a hybrid way or entirely in person, because we’re not sure what the split is in the space sector yet.

The Space Sector Skills Survey 2023 has launched today!

If you’re a UK space employer, take part now to share your skills needs and help address recruitment challenges in the sector👉 https://t.co/e4YWFThVGh #SpaceSectorSkillsSurvey@SpaceEconomics @spacegovuk @SciTechgovuk

— Space Skills Alliance (@SpaceSkills) April 24, 2023

Obviously, you need to be there in person for some jobs, like building a satellite. You can’t build that from home, but if you are doing the design from it and that’s all computer-based, you can probably do quite a lot or nearly all of that from home. So, we’re trying to work out where that split is at the moment.

Action points for the space sector

It’s important for us to look outside the space sector too because we’re guilty as a sector of relying very much on space being incredibly inspiring to attract new talent.

One of the stats is that 86% of people join the space industry because they like space or because the job is interesting, and that’s good, but we don’t have people joining because of pay. We don’t have people joining because they think there’s good career progression.

If we just rely on inspiration and that initial excitement, it’s possibly not enough to make sure that we’re attracting a diverse range of talented people to the sector. It also means we might turn a blind eye to issues such as discrimination, or pay inequality, or career progression.

Space is incredible. We’re literally sending satellites into space and using the data they collect to protect the environment, but we need to make sure that the workforce is there to do that. We need to support people coming throughout their careers, so they’re not pushed away because of negative experiences in the workplace.

Coming up next

Something that we’d like to do in the future is another Space Census. If there is another one, it’ll be three or four years since the last and it’d be really interesting to see if there’s been any changes in the workforce. Are there more women coming through as part of that younger demographic? Are they staying? Have we managed to improve diversity over the last four years? That would be a really interesting longitudinal study.

We’ve also got the chance to see what effect different education and skills programmes have. When Apollo went up, there was an increase in people being inspired to work in STEM. We saw a bump with Tim Peake as well, and we’ve also got three new British astronauts so it would be really interesting to see how we can monitor what effect they have.

If we can start now and start early, we can try and capture that I’d be interested in seeing how their careers help others, but we can’t rely on inspiration alone.