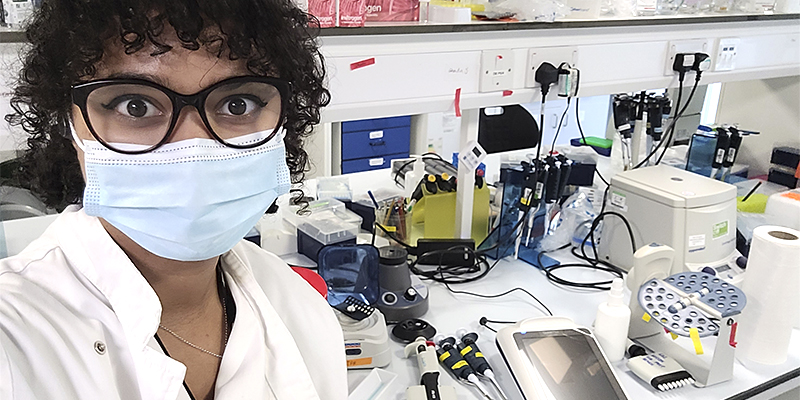

I’ah Donovan-Banfield is a PhD student at the University of Liverpool, focused on looking at the genetic diversity of SARS-coronavirus-2, and how it responds to therapeutics. I’ah developed a strong interest in infectious diseases and immunology during her undergraduate degree in biomedical sciences. She was working in Melbourne, Australia, when the pandemic hit, but returned to the UK to pursue coronavirus research when lockdown eased.

“The contributions of Black people, no matter their profession or passion, are often overlooked or underplayed, and sometimes completely wiped from societal mythology altogether. It’s important to remember that societies are held together by the collective stories we tell ourselves, so we must be included.”

Hooked on infectious diseases and immunology

I grew up in Northwest London and went to a state school for both primary and secondary school, moving to the neighbouring borough for the sixth form.

When I was young, I thought I wanted to be a doctor, but I then realised that I might not enjoy working face-to-face with people all the time. However, I was still very interested in health and the science behind it. So, I applied for biomedical sciences courses at several universities, and I got into St. George’s, University of London. Initially, I was obsessed with blood sciences, but I found studying it quite dull, or at least the lectures didn’t capture my imagination. However, in my second year, we had our first lecture series on infectious diseases and immunology, and that really hooked me.

So, I pursued infectious diseases and immunology in my final year, where my dissertation project looked at a single protein from different bat viruses, to understand how they affect the bat immune response (in a cell model), and if the human response differs.

A strange year in Australia

After my master’s, I went travelling because I needed a bit of a break, but then came back and started working in the same lab but on a different project, looking at MERS-coronavirus, which is a disease that originated in non-human animals (a zoonotic disease).

Then, last year I got a job at Monash University (Melbourne, Australia) in collaboration with the World Mosquito Program (WMP). WMP is a great project that uses a kind of bacteria that inhibits the replication of the dengue virus and other viral pathogens in mosquitoes. This means that mosquitoes with these bacteria in them are unable to infect us with deadly viruses when they fly around biting us!

I moved to Melbourne in January 2020 and had about two months getting over the jetlag and settling in, before COVID hit and we were placed in a very strict lockdown. So, in the end, my project didn’t really get off the ground, so I started looking at PhD programmes back in the UK.

I’m now at the University of Liverpool doing a PhD. I’ve been here for seven months now. My project is focused on looking at the genetic diversity of SARS-coronavirus-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, and how it responds to therapeutics.

COVID-19 changed everything

COVID-19 massively impacted my project in Melbourne. When the pandemic hit, I was helping a new researcher set up their lab, but they got stuck in the UK for the whole year. As a result, I was meeting my boss on Zoom, like everyone else, but with me in Australia and them in the UK, so it was difficult due to odd meeting times.

I ended up looking on findaphd.com, and the first project that came up was exactly what I wanted to do. You don’t ignore signs from the universe – I applied for it and got in!

I’m still super grateful for having been able to live and work in Australia; I met some wonderful people. The WMP project is something I really believe in, and it has proven to have a significant impact on controlling mosquito-borne diseases, which are responsible for a sizeable portion of the global disease burden. And they’re only going to become a bigger problem as climate change makes more regions of the planet hospitable to tropical mosquitoes.

Learning to code during lockdown

As part of my PhD in Liverpool now, I spend a lot of time sequencing, which is essentially taking samples of the virus from patients, extracting the viral RNA (genetic material), putting the RNA on a machine, and looking at the genetic code. Then, I analyse all that data on my computer to work out how the virus is changing, if it is changing, and why.

When COVID hit, I ended up learning how to code, as I couldn’t be in the lab. I didn’t massively enjoy it at the time, but it has really helped me to make good progress on my PhD this year because I’ve been able to use the skills that I developed to analyse my data.

Obviously, now I work from home quite a lot (as many people do), but in the last few weeks, I’ve been in the lab much more as I’ve got many samples to process.

Translating academic research into practical outcomes for society and public policy

I also sit on my funding body’s Knowledge Mobilisation Committee. Knowledge mobilisation is essentially how we translate academic research into practical outcomes for society and public policy. So, how is what I’m doing in the lab is going to be used to better society and help improve health outcomes in the future? It puts into perspective what I’m doing every day. I can sometimes get lost in the minuscule details, which are intellectually challenging, but I also want to make sure that what I’m doing is going to impact the world in a positive way.

I also love communicating science to lay audiences and thinking of new ways to explain complex topics, because I spend all day thinking about these topics and talking about them with colleagues, using a lot of jargon. I like to be able to explain what I’ve spent years and years learning and studying in a two-to-five-minute conversation and have someone walk away feeling like they had a fun time learning something new.

Diversity of thought and power in science is vital

Almost since the inception of the Western scientific method, scientists have exploited vulnerable populations, from enslaved Africans to people who are experiencing poverty in Europe and elsewhere.

An example of this is how the Jewish community was treated during World War II and eugenicist ideology. And before that (and since), many communities have had experiments conducted on them in hideous ways, in the name of science. This was unequivocally disgusting behaviour, with many of the stories untold. This dark history, that’s only just starting to be reckoned with by the scientific community itself, is part of the deep-rooted distrust in many communities of colour. Science still has the power to cause harm to the communities it purports to be helping.

Therefore, diversity of thought and power in science is vital for including communities that have historically been either excluded or badly affected by science and health research. Marginalised people need to be represented in science, but it can’t just stop there; the system needs to change, so minoritised people can be properly included, catered for, and welcomed. However, it’s also important they’re not just tokenised, i.e., for institutes to look better in their marketing materials and give the illusion of diversity.

If the next generation, whether they’re young Black girls, boys, or nonbinary people, want to grow up and be a scientist, they are already acutely aware of the history. They hear from their families, their communities, about the ways they have been mistreated in hospitals, by doctors or by researchers. So, if they still want to pursue a science career because they have a passion for it and want to make a difference, the system needs to change so they’re not the only Black person in the department, and so they have a community that can back them if they want to speak out against any injustices they may experience.

I am a member of an organisation called the Black Microbiologist Association that was borne of the #BlackInMicro movement, started up in the US by two wonderful microbiologists, Dr Kishana Taylor and Dr Ariangela J. Kozik. It was created to showcase the presence and accomplishments of Black microbiologists from around the world. The #BlackinX network also provides a calendar of all the events celebrating Black peoples’ contributions across many other disciplines. No one should be able to say: “I don’t know any Black people in my sector”, the resources are out there – take a look!

Things need to change

The contributions of Black people, no matter which profession or passion, are often overlooked or underplayed, and sometimes completely wiped from societal mythology altogether. It’s important to remember that societies are held together by the collective stories we tell ourselves, so we must be included.

If sections of society are systemically excluded and the history of their mistreatment is glossed over, or only told in half-truths, then we can’t collectively move forward or make up for the past wrongs.

So, for me, Black History Month is a time to reflect on what’s happened to us, what has displaced us. But at the same time, Black History spans much further back than when Europeans first set foot in Africa. There must be a broader range of stories that are told in mainstream education for one, but also mainstream media and the stories that we tell each other.

Black people have always been thinking big ideas and contributing big things to humanity. So, I feel like it’s one way to highlight just how much the Eurocentric/Western world needs to open its eyes and realise that ideas can, and need to, come from other places.

Where we are at now, and the way things are going in society, is a result of hundreds and hundreds of years of extractivism and colonialism: depleting the earth and depleting its people. It needs to stop.

Telling stories louder and clearer

It’s great that we have a month dedicated to telling Black stories that may have been hidden or suppressed over generations. I celebrate it just by getting on with my normal life and I guess I do more outreach. I’ve just moved to Liverpool, so I will try to find a community here and inspire kids into science while being honest about its history.

This morning on Twitter, and I saw some comments asking: “Why do we have a Black History Month, and not a White History Month?” They haven’t thought that they read all about their history in school, whereas Black History was all about slavery.

That’s a terrible section of history that needs to be discussed, but that’s not all that Black people have experienced in humanity, and so it’s important to balance that so the Black students in those classes don’t feel victimised, or that they can only be seen in a particular light.

There are plenty of ways that Black people have contributed to society. One example that I have from biology is a former enslaved African man, Onesimus (sadly, his birth name was never recorded), from the 18th century. He introduced the idea of inoculation against smallpox to his master and helped to end an epidemic in Boston, USA. This method was widely practiced in Sub-Saharan Africa and was instrumental in the development of vaccination by Edward Jenner decades later.

So, to me, Black History Month means our stories being told louder and clearer, and I guess we get to celebrate in this one month, but society should continue doing it year-round. We experience racism and other injustices in October, just like every other month of the year. There’s still a long way to go.

The first permanently installed public statue of a Black woman by a Black woman in the UK

The fact that there is a statue of Henrietta Lacks in Bristol is great. My first ever experience in the lab, around seven years ago, was using HeLa cells, and I had no idea of their origin. This is a topic that could easily have been covered in a lecture or tutorial, so the fact that it wasn’t was a massive oversight.

So, I’m glad that my alma mater has commissioned the sculpture. The statue is in the place I used to go on my lunch break all the time, like many students, and it’s cool that they’ll be able to see it and read about Henrietta’s story and realise how she contributed to science.

The University of Bristol, like many other older institutions, started with funding that stemmed from the transatlantic slave trade, so they owe a lot to Black communities and amplifying Black stories is just one small step towards that. The companies that still profit to this day from the sale of HeLa cells need to think about giving some of that profit to Henrietta Lack’s family. This story highlights what Black women have experienced at the hands of researchers, as a lot of early gynaecological experiments, including those performed by the so-called ‘Father of Gynaecology’ were performed on Black women without their consent.

There’s a lot to be reckoned with, but it feels like the right direction – to tell the stories – because if you don’t see and you don’t hear about these stories, how can you look them up? How you can be outraged? How can you demand change?

Well-earned rest

I’m excited about a lot of different things as I’m just starting my PhD journey. I’m excited to start participating in public outreach programmes in my local area, at primary and secondary schools. I love the light that shines in kids’ eyes when they learn about something cool for the first time.

Besides that, I’m also excited to take a holiday. I started my PhD in the middle of lockdown, and I’ve been on the go ever since, so I want to take some time to rest, which I think is important for people who are in spaces in which they are underrepresented.

Sometimes you feel like you must work over and above what is reasonable and sometimes that expectation is overtly put on you, other times it is implied. Either way, I try to make sure that I give myself the rest I need because I am not my best self when I’m exhausted (who is?) – it’s just about learning when to put your foot down and say how you feel.

Read more about I’ah’s research here:

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5124-2427

https://www.linkedin.com/in/i-ah-donovan-banfield-b86aa0112/