Professor Jan Godsell joined WMG [Warwick Manufacturing Group] in October 2013 from Cranfield University School of Management, the next step in a career that has been split between both industry and academia. Beginning at ICI / Zeneca Pharmaceuticals and then working her way up to senior management level at Dyson, in both supply chain and operations management functions, Jan built a successful career in industry before moving into academia.

“…The only place I ever got some surprises was Japan when I went for my first internship and I got off the plane, they picked me up and said, “Oh! You’re a woman!”, because they’d never seen a female engineer before, or at least a female mechanical engineer…”

Route into manufacturing beginning with a pre-university placement year

I started from a very young age, probably from about 15, knowing that I wanted to be involved in manufacturing. In the sixth form I went on an insight course for getting girls into engineering and that confirmed it was a good way into manufacturing, but mechanical engineering was perhaps a broader base than straight manufacturing / engineering.

I was sponsored from school by ICI, so I did a pre-university year with them. We did a lot of training that people would now do on a graduate scheme, which was amazing. We did three months’ workshop skills, which we did with the apprentices. We did three months’ work shadowing with tradespeople on site, three months’ design and make project where we designed a sensory playground for a local special needs unit. And we did three months of our own specific projects. ICI guaranteed us a summer vacation placement every summer.

Open minded and holistic support from ICI

The day that we joined ICI at 18 they registered us with one of the institutions, so I was going to do mechanical engineering and I was registered with the Institution of Mechanical Engineers. It was a very holistic programme and I feel they were very open minded because they insisted that our first summer vacation we didn’t work for ICI, but we worked in a non-English speaking country of our choice and they would pay the bill, so I went to Japan.

Internship in Japan

It was 1990 and Japanese manufacturing was very, very ‘hot’ and so it was the place to go if I wanted to find out more. I got an internship with Sumitomo Heavy Industries, just outside Tokyo for their ski lift gearbox division, which was great. Although I’d started to learn some Japanese, I was pretty useless at this, but with practice I began to improve.

I did a four year undergraduate masters at Birmingham University in Mechanical Engineering Manufacture and Management with Japanese. It was an excellent degree.

Scholarship to work and study in Japan

I then applied for a scholarship from the Tokai Bank, which they offered to one student at Birmingham University to spend a year in Japan studying Japanese at Nanzan University and living with a Japanese host family. I was very fortunate to get that, so I did two years of engineering and then one year of studying Japanese at Nanzan and at the end of that I did a three month work placement for ICI.

They were building a new chemical plant in Mihara, which was actually for the automotive industry. They made a refrigerant that went into cars and they’d developed one that was CFC free, but they believed to penetrate the Japanese car market they needed to have a manufacturing plant in Japan.

Two job offers after university

On finishing my degree I was very fortunate to have two job offers – one from Shell Exploration and Production and one from ICI. I did a double summer vacation placement at the end of my third year. I did six weeks with Shell and three months with ICI. I got to go offshore which was very exciting, but decided to stick with what was then the demerged part of ICI – Zeneca (now AstraZeneca) – because they’d been very supportive of my career to date.

I started work in Macclesfield as a technical support engineer for the tablets packing facility and within a year I then became a front line manager so that I was supervising my own shift manufacturing tablets.

Joining Dyson – a fast moving company with an entrepreneurial spirit

From there I needed to move to the South West for personal reasons and I saw an advert for an ‘SME’ called Dyson and got a job as a production engineer for their manufacturing line for their DC03 vacuum cleaner. Dyson was a very small company at the time, probably just growing to about 400 people, moving extremely fast and because I had this big company training and Dyson has a very entrepreneurial spirit, so the world was your oyster.

It was fantastic for me – I went from being a production engineer to running a night shift for them, the introduced an ERP [enterprise resource planning] system to their logistics function which didn’t go so well, so I came in and ran their logistics function for six months, got the system settled in, turned the team around, helped recruit a replacement.

I was then an operations manager for research and development for a period, helping to provide the early operations support to R&D projects right from blue sky thinking through to commercialisation. We provided all of the supply chain functions, whether it was planning or procurement or manufacturing skills to support those projects at different stages.

End to end supply chain review supported by a more holistic view

I then went on to do a strategic review of the supply chain for Dyson from end to end. That was the when the term ‘supply chain’ first started being used – historically it had been ‘operations’.

For some companies that means just manufacturing, whereas my operations director was ex-Mars and he had a much more holistic view of the supply chain through from customers, all of the operations planning, purchasing, manufacturing and logistics through to the suppliers, and so I did a strategic review of all of Dyson’s supply chain, which linked into a review of whether or not they expanded in the UK or would offshore to Malaysia.

Opportunity to research making supply chains more customer responsive

On the basis of the review we did they started to expand in the UK and put the Malaysia offshoring plans on ice. I was doing that project at the same time Dyson supported me to do an executive MBA at Cranfield, which was great and so the two tied together and it also formed my thesis project for my MBA. Whilst I was there I was coming up to 30 and Cranfield approached me and said, “We’ve got out first Government funded projects to look at home to make supply chains more customer responsive. Would you be interested?”

Move to academia for a broader impact on more companies and better work / life balance

After doing the supply chain review piece I was running Dyson’s mould shop, which was 24 hours a day, seven days a week, only stopping for a week at Christmas – so an absolutely relentless job and I thought, “It is going to be very difficult to have a family and have a full on manufacturing job.”

I decided that going into academia gave me a better opportunity to have a broader impact on manufacturing – rather than just helping one company I could help a number. That also gave me better work / life balance so I could have a family and still maintain a professional career.

I progressed through the ranks at Cranfield and I registered for a Ph.D. part-time, which I got in 2008. I developed a portfolio of work around end to end supply chain thinking – very, very industrially focused, always working with companies. I was looking at how to better align marketing, product and supply chain strategy, so coming right the way back to my pharmaceutical roots.

Career serendipity

I now worked with well over 100 different companies doing that and it will be two years in October that I left Cranfield and got the role at WMG which ironically, is always a place I aspired to work. Way back in 1995 when I was just leaving university and working for AstraZeneca, as it was then, they started to work with WMG on Zeneca’s manufacturing strategy. I’ve been very familiar with many of their models and approaches from very early on in my career, so it seemed like a natural place to go.

Strong impact on policy to encourage more supply chain orientation in UK industrial strategy

I absolutely love the way they engage with practice and it gave me an additional dimension when I did set up my own research group (I head up the Supply Chain Research Group at Warwick). With Lord Bhattacharyya’s connections, we have a strong impact on policy in order to make some of the more fundamental changes that we need to take more of a supply chain orientation in terms of the UK’s industrial strategy, rather than just a pure manufacturing one, so we’re much well placed.

Just recently I’ve been asked to be part of the BIS Manufacturing Advisory Group and I think that was a result of a term paper that we wrote for the All Party Manufacturing Group. They are starting to position UK manufacturing as part of a network of global supply chains.

Supply chain – balancing demand and supply

Supply chain is about how you balance demand and supply. It’s about looking into your fundamental business strategy. Perhaps historically people focused on operations.

When you think back to the 1980s and 1990s, a lot of the big companies had big marketing (so brands) and big manufacturing. Then we went through a period of offshoring manufacturing and many of our big organisations just focused on their brands, because not only did they offshore manufacturing, the outsourced it as well.

Not just about manufacturing

Supply chain is slightly different. It’s not just about manufacturing, it’s about all of the processes that are involved with the balancing of demand and supply, so planning is really the glue that holds it all together, so it would include the purchasing, the manufacturing and the logistics. For me it’s very end to end – you need to look at the conversion of demand from the customers of the firm that you’re looking at to their supply base.

Where some people go a bit wrong it they think supply chain is supply base management. Particularly in an automotive context, people talk about ‘the supply chain’ when they’re really just talking about the suppliers. That’s a very narrow view of supply chain because that’s just focused on managing your suppliers, but actually some of the huge benefits come from working right the way across the chain, across multiple echelons.

Winning by taking an end to end perspective

So recently I commented on the issues we’ve had with the dairy industry. The people who are winning there are taking an end to end supply chain perspective. You’ve got the retailers, so the supermarkets – the more advanced ones have created what they call ‘Dairy Development Groups’ because they appreciated they needed to support the farmers, so there you had the retailer, the milk processors and the farmers all working together end to end to support an industry.

Getting partners in the supply chain working together towards a common good

A non-supply chain focus would just be a farmer working on their own, a processor working on their own, or a supermarket working on their own and the problem is every time you get that you get a stand-off between the two, which is inefficient and that’s what makes our industries inefficient.

I think the way forward for the UK is to work out where we can be more efficient by joining all the partners in the chain together and getting them to work towards a common good, rather than one party in the chain grabbing all the benefit and exploiting other bits of the chain.

The automotive industry: Resurgence at top level

The automotive industry is one of those industries where we’re seeing a resurgence right at the top level. So for instance Jaguar Land Rover is very successful at the moment, Nissan has still maintained its presence and so have Honda and Toyota. It’s interesting to see how much of the underpinning supply chain is locally sourced, or still sourced within the UK.

I think the recent issues with Operation Stack have shown that we’re exposed because we don’t necessarily get things from the Far East, but for some of the high precision components I know some organisations are still very dependent on German precision engineered manufacturing.

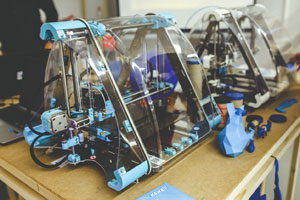

Distributed manufacture: Opportunities to apply 3D printing technologies

3D printing is part of something we call ‘distributed manufacture’, so it’s a return to being able to make things in a more localised way but it’s based on technology. I think this is why we need to take a supply chain perspective.

It could be a consumer at home sits there and orders something through the Internet and there could be a virtual planning hub which then works out for instance that this component has five different parts – one is machined, one is 3D printed, one may be made of wood. They can then send those orders off to three different manufacturers of those parts, coordinate those three bits being put together and then sending them to your home.

Using the Internet to communicate in a more networked way

3D printing is a technology that is bringing to people’s minds the ideal of localised manufacturing, but actually it’s the fact that the Internet is a way that we can communicate in a more networked way that’s really supporting that.

People have picked up 3D printing technology because it’s much easier to envisage it, but if I have a 3D printer on my own it doesn’t help. What I need is that connectivity for other people to be able to see my printer as part of a bigger network that they can connect to, so they can see that I have a capability to supply and I can then work out where the demand is for my product.

Internet technology giving visibility to demand and supply

Internet technology gives visibility both to demand (what do people want and where the people are who want it) but also to supply, so it enables the suppliers who are much smaller to be able to be seen.

It’s also about the planning and the coordination, not the manufacturing capability per se. If we’re operating in a more distributed way it makes logistics much more important too.

Rebuilding capacity in the lower tiers of the UK automotive supply chain

The Germans can still be scathing and say [to UK car manufacturers], “You’re good at manufacturing cars at the top level – but your automotive supply chains are hollow, you don’t have the capability down at the lower tiers,” so I think our challenge not only based on our existing models, but also for the new low carbon mobility solutions for the future is to make sure we start rebuilding the capability of the automotive supply chain at the lower tiers. Then we’ve got something that’s much more solid.

Automotive – a cyclical industry that needs a supply chain perspective

You need to make sure that people are profitable so that when they have to pull back in they can still survive, so again by taking a supply chain perspective and taking out the efficiencies you’re more likely to enable that to happen.

A broader supply chain perspective to drive diversity

By taking a broader supply chain perspective they’re likely to include more women. At the moment, coming through an engineering degree where it’s still about 10% of engineers who are women, I know that in the aerospace industry companies like Selex ES have now got up to an equal gender mix on their engineering apprenticeship – they’re 50 / 50.

Rotating work placements to help girls realise they are capable of commercial engineering roles

They did this by getting children in when they were 15 or 16 on extended summer placements but they rotated round all of their opportunities for commercial engineering, and by giving girls the opportunity to see all of those, more of them chose to go into engineering, whereas if you forced them to choose their work placements they may have thought they weren’t capable of doing the engineering bit and chose not to, so by letting them see it subtly meant that more girls realised they could do it.

For me that exploded a big myth. I thought maybe that only 10% of girls wanted to do engineering and you couldn’t fight against nature, but they showed that perhaps by giving people the opportunity to see for themselves that they can do these roles you can get better gender diversity.

Reframing opportunities so girls see them as more attractive

If you think about the supply chain you’ve got purchasing, which is essentially shopping – girls are great at shopping. You’ve got planning, which requires a lot of data analytics skills that are about seeing the bigger picture. You’ve got the whole logistics part as well as the manufacturing part, so I think if you look at it as a whole you’ve got far more opportunities that girls might see as attractive and want to go in to.

When I look at our Masters courses in Logistics and Supply Chain, the gender balance is almost 50 / 50, whereas I think if you look at an engineering course, then you’re still at 10 or 15%.

Essential opportunities: Engineering insight course at 17

I went on an insight course, which was about women in engineering, at Brunel University when I was 17. That cemented the fact that I was going to do engineering and one of my good friends now is someone I met on that course. We met on that course at 17, didn’t see each other for a number of years and then started work at Dyson on the same day and we’re still friends now years and years later. I think those sort of opportunities are essential.

Women in engineering bringing a breath of fresh air and a different perspective on problems

I have never ever in my life come across any form of discrimination for being a woman in the UK. If anything there’s possibly been slight positive discrimination and I think if you’re willing to go with the flow you can use your femininity to your advantage, and not in a manipulative way. You bring a breath of fresh air in and sometimes we look at problems in a slightly different way. If you can get those points across in a way that’s not seen as aggressive then actually you have a bigger voice.

“Oh! You’re a woman!”

The only place I ever got some surprises was Japan when I went for my first internship and I got off the plane, they picked me up and said, “Oh! You’re a woman!”, because they’d never seen a female engineer before, or at least a female mechanical engineer.

It just wasn’t what women studied and that’s far more embedded in their culture, because when I did my second placement, the company who was managing the contract there (not ICI) said, “Does she have to be here? She’s a woman. We don’t have women on the building site,” so ICI said, “Well in the UK we won’t discriminate, so yes, she does have to be here.”

Encouraging everybody, not just girls into engineering by talking more about tangible job roles

The chap who I was working with said to me very nicely, “Why do you want to do this? You’re ruining your marriage prospects.” He didn’t mean it rudely or aggressively, it was just poles apart, but in the UK I’ve never come across any form of discrimination, so sometimes it’s about encouraging everybody, not just girls, into STEMM subjects and engineering. It’s about encouraging everyone across the board to look at how supply chains support our day to day lives, to perhaps take out more about the roles, not the functions.

We talk about ‘engineering’, but that doesn’t mean anything. What job does an engineer do? If we were to talk more about job roles and things that you can do and make it much more tangible for both boys and girls, I think we’d encourage more people into both supply chain and manufacturing.

Opportunity to move towards looking at the social aspects of the supply chain to increase diversity

This is a personal view, but I think we put a significant amount of effort into looking at the environmental standards around our suppliers. If we look at a company’s corporate social responsibility policy when we do a supplier assessment, one of the major legs we focus on and develop lots of frameworks around is the environment, so water usage, carbon footprint, all of those sorts of things.

It was a female student of mine who was looking at modern day human slavery and what dawned on me as she was talking about it was that many of the frameworks which are used as assessments for firms which have been developed to look at the environment could also be used to look at the social aspects of the supply chain, whether than is diversity or the use of modern day slavery or other dimensions.

When we look at these policies we seem to shy away from the social part and focus more on the environmental part and what you’ll tend to find is that many organisations have these supplier assessments, but again they’re slightly hollow when the box is ticked and it all looks OK and they go with one supplier but you don’t know what they’re doing in terms of suppliers’ suppliers.

Painting the supply chain in its broadest spectrum to encourage as many groups as possible to participate

The problem tends to get hidden away in the lower tiers. What I would say in terms of increasing diversity is that because it should not just be diversity of women but all forms of diversity, we should perhaps paint the supply chain in its broadest spectrum – that is, supply chains feed our nation, educate our nation, they keep us safe, they provide our homes, they provide our food, they provide our clothes – and paint those opportunities in a way that would encourage as many different groups as possible to want to participate.

Using ‘real option value’ to maximise women’s career choices

The decision that I made to leave industry and go into academia was an absolutely critical decision in enabling me to maintain my professional life, but whilst balancing work and family life. I talk about the idea in supply chains of ‘real option value’ – how do you make a decision today that gives you as many options in the future? So my decision to be a mechanical engineer and not a manufacturing engineer was to keep my options open.

In Warwick Manufacturing Group we have a lot of female professors, but I’ve never seen it being an issue. I don’t believe I’ve been discriminated against because I’m a woman. If anything I’d say that because universities are so concerned about diversity at the moment that it might act in your favour.

For girls to give themselves the best chance I tell them to think about the option value all the way through the stages of their career, so when you’re doing your A-levels, pick the subjects that give you the most options.

Women (or men) becoming professors: Something to consider much earlier in your career

I’m very fortunate that I managed to have an industrial career and then make the transition to academia. Things like the REF [Research Excellence Framework] and the requirements now for publication would make this very, very difficult. I couldn’t necessarily have been employed in the way I was at Cranfield now because I would have been expected to have a doctorate first, so I think if you truly want to become a professor it is something that you need to consider much, much earlier in your career, whether you’re male or female.

I would plan your career very carefully all the way through the different stages, so thinking about your A-levels and thinking about your choice of undergraduate degree. So something like engineering, so especially with broad spectrum mechanical engineering keeps your options open.

New engineering doctorates creating alternative routes

I would argue to get some work experience first for two or three years because it helps put everything into practice. So WMG offer something called an engineering doctorate which enables to you to work whilst getting your Ph.D. I think that’s a great route again to get your industrial experience of getting a Ph.D. and it keeps your options open about whether you want to go into industry or academia.

Building your profile and gaining recognition

The critical thing though, which is different from my day is that you need to start publishing early and getting into that mind set about publishing the stuff that gets you externally recognised in terms of perhaps practitioner pieces or specialist practitioner magazines, but also getting yourself know through academic journals so that you begin to build up your academic kudos.

You also need to consider very carefully where you do your Ph.D., particularly in the field of management. A lot of the higher ranking journals are very skewed towards the U.S., so would you therefore want to spend some time in the U.S. so that you start to build a network there so that you’re more strategically linked in to that network in terms of publication in some of the journals?

I don’t think being a professor these days is something you can fall in to. It was a little bit more in my day. I think you now need to be quite strategic about it whether you’re male or female. I have to say it’s one of the jobs that gives you the greatest opportunity (if you’ve got the right employer) to be flexible. It’s probably one of the best ways that a woman can achieve increasing specialism and recognition whilst balancing family life.

I don’t know if it’s just the institutions I’ve worked for, so Cranfield and WMG, but what I’ve been able to achieve whilst having a family, getting good quality time with my family, I’m not sure you’d get in many other roles.

https://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/sci/wmg/people/profile/?wmgid=1003

http://www.wmgshapingthefuture.co.uk/author/jan-godsell/

https://twitter.com/jangodsell