Hazel Reeves is a figurative sculptor with a curiosity for people, their faces, and she is passionate about telling stories of struggles for social justice and redressing the lack of women represented. She works to commission in clay for bronze, using her statues as a catalyst for change, to engage and move people. Hazel is perhaps best known for her bronze public commissions such as the suffragette, Emmeline Pankhurst in Manchester, the women biscuit factory workers, the Cracker Packers, in Carlisle, and most recently, her statue of Elizabeth Wolstenholme Elmy, which was unveiled on International Women’s Day 2022.

“I’m never happier than when I’m telling the stories of the struggles for social justice in bronze, and in particular, redressing the lack of statues of women, one statue at a time.”

Getting back in touch with childhood loves and fulfilling long-held dreams

From a young age, I was drawing all the time. I wanted to go to art school just like my older sister, Sandra, but my parents put their foot down. I was told that “art is a luxury” and I had to do something more academic, so I gave up all the subjects I excelled at, including art, and took up the sciences. It took many years to realise that I should have been an artist all along. But I got there in the end.

How did I make the transition? It suddenly came to me. I was going to be a portrait sculptor. Even though I had never sculpted or done portraits. I can only think that this was a result of six months working in the Dominican Republic for the UN on women’s rights. Being in such a different and vibrant environment caused me to get back in touch with my childhood loves of dancing, music and art. It has taken many years, but finally I am fulfilling my dream, doing what I should always have done.

The last of my many careers

As sculpting is the last of my many careers, I didn’t go through the usual and more formal art school route. So, I guess I did the equivalent of putting myself through art school, with a patchwork of continuing education courses. Then this hobby became more serious, culminating in a thoroughly inspiring month sculpting at the Florence Academy of Art. I finally dropped my work promoting women’s rights internationally to become a full-time sculptor.

My first quasi-public commission was for a peace garden in Wales, of Sadako Sasaki, the young girl who died from the impacts of the Hiroshima bomb. The story of Sadako and the 1000 paper cranes is still used in peace education internationally. The statue was unveiled in 2012 on the International Day of World peace. This was featured in December as one of The Guardian’s top 10 of Britain’s best small pilgrimage sites.

A curiosity for people, their faces and their stories

So, if I had to sum up my artistic background: I’m a figurative sculptor, working to commission in clay for bronze, with a curiosity in people, their faces and their stories.

My life-long activism weaves its way through my artistic practice. I have managed to combine my passion for promoting women’s rights and my passion for figurative sculpture in recent commissions. I’m never happier than when I’m telling the stories of the struggles for social justice in bronze, and in particular, redressing the lack of statues of women, one statue at a time. I want to engage and move people – moving them to tears, to ask questions, to participate, to tell their own stories, to mobilise. A statue must be a catalyst for change.

I’m perhaps best known for my bronze public commissions such as Sir Nigel Gresley at King’s Cross Station, the women biscuit factory workers – the Cracker Packers – in Carlisle, suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst in Manchester, and now Elizabeth Wolstenholme Elmy, in Congleton. You may have seen these on tv.

I’m a member of the Royal Society of Sculptors (MRSS), the Society of Women Artists and Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts (RSA).

I live and work with the spinal condition axial spondyloarthritis (AS).

The role of a sculptor (other than sculpting!)

In my role, every day is different.

During the last stages of a public commission, I am in the studio every day until late, working with my live model, striving to perfect the statue, before the foundry team come to make the rubber mould. I completely immerse myself. Once the foundry has the mould, I have to travel up and work with the team at Bronze Age London, ensuring the final bronze is as close as possible to my final clay sculpture. Then I am there at the statue’s final location, to oversee its safe installation prior to the unveiling.

In a regular week I have a real mix of work, including but not only the act of sculpting. As with any self-employed person, I have to undertake a lot of desk-based work rather than studio-based work. I have all the publicity, including media interviews, talks to the public and societies, updating my website, social media postings, to do.

I also have to keep an eye out for commission opportunities, although often I am directly approached by potential clients. Once I am interested in a commission then there is a lot of work involved – creative, research, budget calculations – to secure it, including discussions with the potential client. And, of course, there is all the financial management.

As an artist, I also have other areas of artistic interest. My artistic practice is underpinned by the idea of choreography. Yes, choreographing stories in bronze, but also choreographing dancers, choreographing the sounds of nature. The outputs vary but the motivation remains the same. I want to move people, literally, figuratively.

For the movement and sound-based work I undertake artist residencies – last year I was artist-in-residence at Knepp Wildland, the renowned rewilding estate, and I had a residency at the Fabrica Gallery in Brighton.

Our Elizabeth: pioneer, visionary, radical, pacifist, humanitarian, atheist

The amazing Elizabeth’s Group was formed to raise awareness of Elizabeth Wolstenhome Elmy’s national contribution to women’s rights and commissioned me to tell her story in bronze. We had an incredible day on 8th March, International Women’s Day, when after a joyous march through the town, the incredible Baroness Hale of Richmond, former President of the Supreme Court, unveiled the statue of the equally incredible Elizabeth.

Elizabeth Wolstenholme Elmy (1833-1918), was my kind of feminist – a pioneer, a visionary, a radical, a pacifist, a humanitarian, an atheist. She lobbied for equality throughout her life, working tirelessly for girls’ education, for women’s right to own property and for their right to vote.

The statue – now affectionately known as Our Elizabeth – shows her life-size at 4ft 10 inches, in full flow engaging passers-by, showing how she powerfully and persuasively used words to bring about change in the world. Perhaps she is urging women to demand the vote. Or promoting the importance of girls’ education to reluctant fathers. Or arguing that women must be able to own their own property and keep their earnings.

We need more role models on our streets, reminding us that women have always done extraordinary things. I hope the statue will inspire young girls to carve out their own life journey, unconstrained by conventions and stereotypes. And inspire the next generation to carry on her work for women’s rights and to challenge violence against women.

Elizabeth shows us that it doesn’t matter whether you are young or old, are tall or tiny in stature, you too can make a difference. And if you consider she was only allowed two years of formal education, given she was a girl, her achievements are even more remarkable. She lived in Congleton, Cheshire.

The woman who inspired Emmeline Pankhurst and the brains behind the suffrage movement

What an honour to sculpt not one but two heroes of the suffrage movement – Emmeline Pankhurst and Elizabeth Wolstenholme Elmy. Elizabeth was born 25 years earlier than Emmeline (1858-1928), and was a real inspiration to the young Pankhurst. In 1871 Elizabeth became the first paid employee of the women’s movement when she was paid to lobby Parliament with regard to laws that were injurious to women.

Elizabeth was introduced to Emmeline and they became firm friends. She worked with Emmeline to found the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) in 1903 and they worked tirelessly together to fight for women to have the vote. Emmeline described her as the brains behind the suffrage movement. They parted company in 1913 as Elizabeth opposed the increasing militancy of the suffragette movement.

In 1912, the newspaper of the WSPU stated “If the women of England ever realise what they owe to Mrs Elmy they will put up to her memory a national monument”. 100 years later, that prophecy was fulfilled. You can watch a video of the unveiling here. There’s also a BBC North West local news report here.

Recognition

I was blown away that Rise up, women [see main header image], my statue of Emmeline Pankhurst in St Peter’s Square, Manchester, had been shortlisted for the 2021 Marsh Award for Excellence in Public Sculpture alongside amazing artists Phyllida Barlow, Briony Marshall, Thomas J Price, Mark Richards and Rachel Whiteread. You can imagine how ecstatic I was when I found out I had won!

The judging panel was impressed by the originality of the design of the sculpture in the way that I’d used a domestic chair in the place of the traditional, ubiquitous plinth. In my acceptance speech I declared I was “absolutely thrilled that a statue of a woman, sculpted by a woman, has received such an accolade”. I dedicated the award and the prize money to our “modern-day Emmelines, who work tirelessly to challenge inequality and violence, because in their hearts they know that change is possible.”

Our Emmeline was unveiled to a 7000-strong crowd, on 14th December 2018 to commemorate the 100 years since women in the UK first voted in a general election. The statue has been warmly embraced by the local community since its unveiling, being a place for vigils, protest, celebration, reflection. Here is a video of the whole project from inception to unveiling.

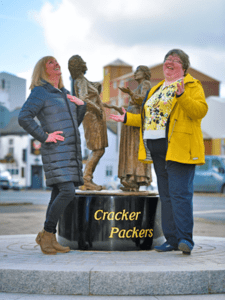

Celebrating the ‘Cracker Packers’

It was a joy to celebrate in bronze the lives of women biscuit factory workers – the ‘Cracker Packers’ – from Carr’s (now McVitie’s). Such stories of working women’s lives rarely make it into formal history yet need to be celebrated and shared with future generations. The statue was unveiled by the Cracker Packers themselves, past and present, on International Women’s Day 2018 in Caldewgate, Carlisle. You can see the whole journey with this documentary by Huckleberry Films (7m 33s).

Former and current Cracker Packers helped me choreograph the pose of the two women factory workers, one from the past and one from the present, captured in story-telling and happy chatter, atop a giant Carr’s Table Water Biscuit. Our workshop was memorable, full of laughter as these women generously shared their stories of life as a Cracker Packer. The final statue effuses this humour, warmth and camaraderie and has become a much-loved local landmark.

Noble and heroic women

Art in the public realm has been representing ‘noble and heroic’ men since the beginning. But where are the noble and heroic women? Some five years ago an analysis of the statistics showed that only 2.7% of all statues in the UK were of historical, non-royal women. That’s 25 statues.

Since then there have been efforts to start redressing this lack of representation of women. In fact, I have contributed four statues of women – Our Elizabeth, Our Emmeline, and two Cracker Packers! The Public Statues and Sculpture Association has recently developed a database of statues of women, focusing on named non-royal women as well as ‘generic women’, which will help us to update the statistics. Every new statue of a woman will be added, including Our Elizabeth.

Public art should reflect the public, in its diversity. Commissioning of new statues and public art should be driven my community interest, engagement and ownership. How could we see our society, in all its glory and diversity, represented on our streets in bronze?

We need more statues of relevance to communities today, that reflect the diversity of our populations in terms of gender, but also race, ethnicity, dis/ability, class, sexuality. An important question to address is how to get communities engaged in the selection and design of a statue. The Womanchester Project asked the public which Mancunian they wanted to celebrate in bronze. The answer, overwhelmingly was Emmeline Pankhurst.

An audio story of hope

What’s next? I have had to put a number of smaller-scale sculptural projects on hold while completing Our Elizabeth. But, I am also really looking forward to some time to explore my other artistic interests, at the intersection of soundscapes, movement and nature. The dawn chorus is starting up, so it’s time to dust off my recording equipment and go out into the scrubland at Knepp Wilding and capture its audio story of hope. My obsession is with the Nightingale population there, so rare elsewhere.

Main image credit: © Karen Wright