Dr Andy Mycock is a reader in Politics at the University of Huddersfield and his current research focuses on the development of active citizenship and democratic participation of young people in the UK. He has published widely on issues of youth citizenship and government youth initiatives such as National Citizen Service. Andrew has arranged to the University of Huddersfield to host a touring exhibition from the House of Commons, the centrepiece of which is a LEGO model of a suffragette called Hope.

“The #StandWithHope campaign is about democracy in all forms, and the danger is that we focus on gender equality at Westminster, but we don’t think about local government, which is still a bastion of the so-called ‘male, pale and stale’.”

Becoming a working-class academic and ally for gender balance in politics

I have a non-traditional route into academia. I worked in an engineering factory for ten years after I left school. Watching the situation with Ukraine, it reminds me that it was only when I went into Interrailing in 1991 that I first met refugees, from the Yugoslav Wars, but I hadn’t got any real idea about what was happening. It was this which helped me decide that I might need to go to college and educate myself about politics, so I went to the University of Salford as a mature student, and I enjoyed it so much I didn’t want to leave university, so I decided to become an academic.

Academia is a strange career. In many ways, I’ve always suffered a bit from imposter syndrome. I’ve always felt like an outsider. It’s interesting when I reflect on my role as an ally for gender balance.

Because academia has been very much defined by masculinity and by dominance of men, particularly in managerial and leadership roles, and also men from a particular background — there are not many working-class academics even now, so I’ve often found that it’s with my female colleagues that I have a sense of professional collegiality.

When I was doing my PhD, particularly, which was an enormous strain, in terms of just being able to afford it, it was my female friends who supported me and help me to get over the line, so I’m very aware of the obvious structural inequalities that still reside in academia.

The ongoing journey towards gender equality

I’m a reader in politics, so my work is mainly research-based these days, although I still enjoy teaching.

It’s interesting that in the classroom over the last 20 years I’ve been in academia we’ve seen not only a growth of young women studying politics, but there is also a resonance in terms of what is taught and how it’s taught, and that’s had a really profound effect. I think it’s a journey, which is still ongoing. This is often taking place in an environment where the changes in society haven’t quite permeated into academia, so those inequalities that I mentioned earlier, are very much in evidence.

On a day-to-day basis, my role in inclusion is very much around policy engagement. I am one of the university’s academic policy engagement leads. The kind of work that I’m doing is often very much focused on issues of gender balance and social policy, so at the moment, for example, I’m working with Tracy Brabin, the only female regional mayor in England, working on a project looking at women and girls’ safety.

The project really is shocking in terms of the evidence presented, and the extent of gender-based violence in society. It really does bring that sense about how sometimes the work I do isn’t abstract, it’s manifest every day in its implications. Working on a project like that is very humbling, and quite rightly provokes conversations in terms of the way men behave in a world that unfortunately still seems to be far too comfortable with the kind of misogyny and violence women experience on a daily basis.

Implications of COVID-19

COVID changed academia, and I don’t think we will ever go back, so in the fact that we do more online, we do more sat in our rooms at home rather than at work. In some senses, it may well have diminished some of those social dimensions of being an academic, particularly spending less time with students and seeing students per se. In many ways, I hope that that situation changes, but I think that in some ways that more remote working will continue to influence what the professional does.

Hope on campus

I’ve got close ties with the parliamentary education service at the House of Commons and also with the academic knowledge exchange team, so I’m quite well wired into what happened in Parliament. I was involved through my work with young people and particularly women in terms of youth democracy.

During the centenary of the lowering of the voting age to 18 for all men, and the introduction of the extension of the franchise to women over the age of 21, in 2018, I was aware of the work that was being done. Then when I found out about the LEGO suffragette I wrote off and said that we really would welcome Hope coming to the campus, particularly if we could schedule it around International Women’s Day, and we were very lucky in that they managed to make that possible.

It was even better as they timed it beautifully to coincide with our student union elections. We were very keen to make sure that we tied it into the idea of the 1928 centenary coming up, so equal votes for women and men, with the living embodiment of democracy on campus, the student union elections.

Last year where we had our first student union elections which were entirely comprised of female candidates. This year, four out of the five candidates were young women, so it really does indicate that there’s been a seismic shift on our campus in terms of student democracy, and gender balance. So, Hope coming to campus really was perfectly timed for it.

LEGO logistics

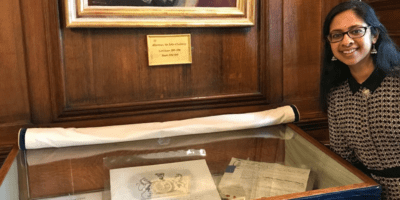

Hope had been lovingly packaged up and arrived in the back of a van from UCL, where she had been displayed last. I received a call to say that she was ten minutes away, but I live in Manchester, and I thought: “If you’re coming to my house that will be one to explain to the neighbours!” But fortunately, she was ten minutes away from campus. She was unloaded and wheeled across the campus where she is residing now until 22nd March.

She is displayed behind a barrier, which is then lowered during the day so students want to give her a cuddle or stand by her for a photo and show some solidarity is there for the issues. In the evening the barrier around her is put back up, not that we have any issues in that our students are extremely well behaved.

Votes for women

I’ve been doing some work on lowering the voting age to 16 over the last few years, and so we’ve been looking franchise changes over the years. The Great Reform Act of 1832, we’ve seen the expansion and slowly of the franchise for men. The voting age was kept at 21 and it’s maintained all the way through to 1918 and beyond. In the main, the expansion of the franchise men is largely based on property rights and wealth, so most working-class men were not given the vote until 1918, in many ways, it is seen as a reward for the sacrifices in the First World War.

At the same point in the conversation, particularly due to the power of the suffragette movement, which of course predates First World War, and in many ways subsided during the First World War as many women made the difficult choice to seen to be patriotic at a time of challenge, meant that the voting age would be expanded to some women over the age 30.

There were some very interesting reasons why. We looked at some House of Commons records. There was a Hansard record of the parliamentary debate of the Franchise Act in 1918, and one of the main fears was that women didn’t have the same level of political knowledge and the same political maturity.

There was also a concern that women, particularly between the ages of 21 and 30, were in a transitory stage and that they were somehow different from men, and that they were maybe potentially more promiscuous or they were less socially responsible.

Equalising political rights

During the debate in the 1920s about whether there should be an equalisation of the vote for women many of the traditionalist parties got vexed about the so-called ‘flappers’. These were women seen as less having less than full moral fortitude, and they were deemed ‘too flighty’. The word is a highly pejorative term and it really does show that at the time, there were some very strong misogynistic tropes that influence that unequal introduction for working-class men and for women in 1918.

It’s only in 1928 that there were finally equal votes, where both men and men and women, without restrictions (unless they were in jail) were allowed to vote at the age of 21, at which point you can say there’s an equalising of political rights. Oddly enough though, it took a number of election cycles for women to gain the habit of voting in anywhere near the same proportion as men.

It is notable when you then go forward and think about 1969 when the voting age was lowered to 18. A number of things drive that, and one of these is the idea that the age at which adulthood is seen to be realised is lowered to 18, and so there’s an urge to synchronise that to the same point. One of the things that drove that was women’s liberation in the 1960s.

The campaign was often driven by women, not men. I think the interesting point is that shift in terms of voice of young women has been very much evidence in the votes at 16 campaigns, and you’ve seen that it is a disproportionate number of young women driving the movement, the same way you saw in 1969, yet, at the same time, we still have to have something called the Women’s Equality Party, which says much about our society and our politics.

Response to the exhibition

Why would a large amount of largely unrecyclable plastic bricks matter? I think these exhibitions matter because they provide a very visual way of engaging with an issue. The interesting point here about the LEGO suffragette is that ten years is a significant period between the commemoration of 1918 and 1928, and the danger is that some of that momentum we saw with women and men marking the introduction of the franchise to some women in 1918 might be lost.

I would argue that the more important date in some senses is 1928, when you not only bring in the principle of female enfranchisement, but you bring in the principle of equality, and in that sense, what we’re encouraging our students to do is come along and to take part in the break of bias campaign, but also to #StandWithHope as part of our student elections.

Wishing all the amazing women I blessed to know “Happy International Women’s day”. Here is Hope, who is in @HuddersfieldUni library.#BreakTheBias2022 #StandWithHope #InternationalWomensDay2022 pic.twitter.com/8Uucz9jvA1

— Sarah Fletcher-Shaw 🌈 She/Her (@sarahjoOT) March 8, 2022

We’ve been very keen to tie the idea of a vibrant living democracy on campus to bring democracy closer to home. This isn’t just about Westminster. The #StandWithHope campaign is about democracy in all forms, and the danger is that we focus on gender equality at Westminster, but we don’t think about local government, which is still a bastion of the so-called ‘male, pale and stale’.

In many ways, it’s older men, usually white, who are overrepresented as counsellors, and there’s a need to be sure that if we have gender equality in terms of representation, it’s across all our institutions, including our Student Union. We’re very proud that now we see on successive elections in our Student Union so many women are standing and being successful.

What do we mean by equality and where next?

In terms of work, I’m doing a project at the moment looking at youth democratic socialisation, so how young women and young men learn how to engage in politics as they grow up from childhood right way through to early adulthood. That’s connected to some work that I’m doing with the British Youth Council, which is an equal votes campaign of a different kind.

The voting age has been lowered in Scotland and Wales to 16 for local and national elections, but young people in England and Northern Ireland do not have to stay voting rights for local and combined authority elections, so I’m working in the British Youth Council and various youth groups to bring equal votes in another way.

That’s the interesting point around equal representation, it doesn’t simply factor around gender or class law, or race, or ethnicity, etc. Equality can be realised in different ways and it’s ongoing work, so, in that sense, Hope being displayed on the university campus is a nice moment for us to reflect upon. What do we mean by equality and then where do we go next?