Bushra Schuitemaker is a zoologist, radio presenter and nature writer. She holds a BSc in Zoology from the Angela Ruskin University in Cambridge and is currently a PhD candidate focused on poultry health and welfare, based at the Quadram Institute in Norwich. Bushra is vice-chair of the British Ecological Society’s REED Ecological network, where she champions diversity and inclusion.

“We’re really starting to recognise the value of diversity, particularly in places where we are needing to collaborate. For me, it’s really important to recognise that environmental justice is social justice.”

Wild about zoology

I am a zoologist. I did my undergraduate degree, so my Bachelor of Science in Zoology, at the Anglia Ruskin University in Cambridge.

I have always loved animals. I decided from about age seven that I wanted to study animals and work with animals, and that led me to zoology. During university I found that I really enjoyed the more hands-on element — I love being practical, being out in the field watching animals or working in the lab, which is also really hands-on.

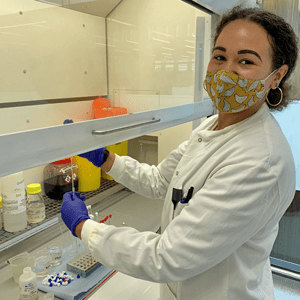

After my undergraduate degree, I decided to work for a few years, so I first started working at the Wellcome Genome Campus based in Cambridge as an animal technician, and then later as a scientist for Cancer Research UK. I really enjoyed the science and all the lab work, but I really missed working with animals, and so that’s what led me to decide to do some of my own research as a PhD researcher. I’m now based at the Quadram Institute Biosciences in Norwich.

Focusing on health and welfare

My PhD project is focused on poultry health and welfare. I’m interested in finding better ways to be able to assess or predict health conditions in chickens, but just using their poo. That’s because we are not going to stress the animal out to collect it and there is plenty of chicken poo to collect on farms, so my days can vary depending on what jobs I need to do.

Part of doing a PhD is independently conducting your own research. So, some days I might be on a farm at 8am ready to collect some faecal samples, and on other days I’ll be in the lab. What I’ll be doing is trying to extract the DNA from those faecal samples so that I can have a better idea of the microorganisms that are present. After all of the work in the lab (so experiments and processing samples) I then have to analyse the data.

This bit is really exciting because you can finally get to see all of your hard work come to a really rewarding end. Once you’ve got that data, you get to present it to other scientists who are working in your area. So, all in all, each day can be quite different, but I tend to break it up— some days I’m on the farm, some days I’m in the lab, and the rest of the time I’m on my computer.

You are not alone

I got involved with the British Ecological Society specifically for the REED Ecological Network. The REED Ecological Network is the Racial and Ethnic Equality and Diversity Ecological Network, and this is a special interest group of the British Ecological Society.

The Society set up these groups so they’re able to support people more specifically. A lot of their groups are more focused on people’s research interests, so you would maybe have a macro ecologist society or perhaps a soil society, but what we’ve done is created a society that is specific to people’s characteristics.

This is exclusively for people who are from a racial or ethnic group that is unrepresented or poorly represented in ecology, so the REED Ecology Network was set up in 2020 and this was on the back of the momentum from the Black Lives Matter movement. I managed to get involved pretty much from day zero.

One day I was just sat at the computer and I thought to myself: “Surely I can’t be the only Black ecologist or zoologist in the UK?” So, I simply did a Google search: “Black ecologist uk”, and what came up was an article that had been published three days previously by the British Ecological Society, written by a guy called Reuben Fakoya-Brooks.

He was a black zoology student who had studied at Nottingham University and discovered that he was the only black person to have taken that course and been taught by his lecturers, and so that posed the question for him: “Why are so few people of colour coming into Zoology. Why am I the only Black person in the classroom?” So, he wrote an article and I immediately reached out and told him: “You’re not alone.”

I had also thought that I was alone, and from here we managed to connect with now over 90 people from around the world who are all ecologists, coming from underrepresented, racial and ethnic groups in order to create the REED Ecology Network.

Environmental justice is social justice

We’re really starting to recognise the value of diversity, particularly in places where we are needing to collaborate. For me, it’s really important to recognise that environmental justice is social justice.

People who are most affected by climate change are people who come from low socioeconomic groups, and very often from different racial and ethnic backgrounds. I don’t think it’s right that based on your ethnicity, your race, your religion, you’ll be subjected to worse water conditions or air quality or lack of green spaces. So, by trying to work on some of these issues, we’ll hopefully try and improve the social landscape as well.

We’d really like to change the view that a zoologist has to be the David Attenborough type. We love David Attenborough — he’s inspired so many of us zoologists, but it’s also important for people to see that you don’t have to be an old white gentleman to be a zoologist or ecologist. Also, by considering and including everyone’s experiences, everyone’s different backgrounds, we can also really help to become more inclusive.

I work in the agricultural sector, which is the least diverse sector in the UK, and this is followed by the environmental sector.

Diverse perspectives can help combat climate change, so for example we can start growing and farming non-traditional vegetables. We can think about different animals as well. We need people who have that experience and those people will come from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds, so I think in order for us to have a more sustainable future it’s really valuable and vital for us to have greater diversity of the people in the sector.

Representation matters

I always think that representation matters. When I was watching TV as a young child, I used to love The Really Wild Show on the BBC, and I was really taken with Michaela Strachan as being a woman on TV who was working with animals. Now that I’m older, I think about how much I would’ve benefited and how many other people might have benefited from seeing a person of colour in that position, particularly a woman of colour.

There shouldn’t be any one way of looking at things. That’s why I really enjoy doing science communication, broadcasting and podcasting, because I really want to show people that anyone can do it.

The other part is that from a young age, I always used to do a lot of drama, singing and dancing. I used to love being on the stage and performing. I think that people often have this idea that as a scientist you don’t necessarily get to do those kinds of things: You don’t get to be creative, you don’t get to have these moments of silliness and to share in your science. I think that’s actually a really exciting part of science.

This is why it’s nice for me to hold on these skills that I’ve got from a young age when it comes to performing and public speaking, but I also think that it’s important to pull in all these different skills and interests that I have in order to better communicate science.

I really think that science should be for everyone, just as I was saying about the stereotypical zoologist, maybe people thinking of someone who looks like David Attenborough. I think in general, for science to become more inclusive, we need to make it more accessible and giving people different ways to access science and to experience science is a great way to do that.

Follow what you enjoy, science doesn’t have to be your exclusive focus

I think if people are interested in pursuing a career in science, this is great. Science is really enjoyable, and I thoroughly enjoy it. I think it’s a really rewarding thing to be able to do as well, and by working in science, I feel like I’m having a greater impact on the world, whether this is by working with chickens or whether it is with human health. I really like the fact that I’m able to give back to society.

I would say always follow what you enjoy. When it came to me taking my A-levels, I didn’t go down a strictly scientific route. I did biology, but I also did media, physical education and English literature because those were the things that I enjoyed, and I’ve been able to draw on all that I’ve learned from doing those different subjects.

Often people think that to be a scientist, and especially to pursue a PhD, you must have this single-track focus. You absolutely need to stay motivated, and you need to be hardworking, but that doesn’t mean that you can’t do other things. It doesn’t mean that you can’t have other hobbies and interests outside of your work.

Actually, these things really helped to build you up as a scientist and as a professional. I think a really nice example of this is one of the recent winners of the Nobel Prize for Physiology/Medicine — Svante Pääbo. He won is Nobel Prize for was looking at the evolution of the human genome and actually looking at when different humanoids were involved in the human genome of what we now know as Homo sapiens.

He was always really interested in history, in particular ancient history. He loved ancient Egyptians, ancient Greeks, that kind of thing, so he took a couple of additional classes when he was doing his studies just out of pure interest.

People say that he would even label his substances in Egyptian hieroglyphics in the lab just to deter others from stealing his reagents, but actually it was his interest in ancient civilisations that led to his current work, and ultimately led to his Nobel Prize, so I think it is really important for people to have a multitude of things that they’re interested in, even if they are deciding to pursue a career in science.

Coming up next

Now that I’m in my final year of my PhD I am looking forward to being able to write up and submit my thesis, which is the main element of the project. It’s very scary to see it all coming to a close, but also really exciting to see all of my hard work brought together.

More immediately, I’m going to be talking at the Norwich Science Festival on Sunday 12th of February. They have ‘food and farming’ themed day, and that’s going to be at the Norwich Research Park.

I’ve got a few chicken-related activities for people to get involved in, and I’m also going to be doing a talk, which is about why chickens are so important and why their gut health has such huge implications for both the agricultural industry as well as human health, so there’ll also be some fun quizzes involved.

Generally, I do like to do quite a lot of social media as well, so you can often keep an eye out on Instagram and Twitter for what I am up to.

Reference links

- https://www.linkedin.com/in/bushraschuitemaker/

- https://quadram.ac.uk/people/bushra-schuitemaker/

- https://www.instagram.com/bushybio/

- https://twitter.com/BushyBio

- https://www.britishecologicalsociety.org/membership-community/reednetwork/

- https://www.instagram.com/reedecolnet/

- https://mobile.twitter.com/reedecolnet

- https://quadram.ac.uk/

- https://twitter.com/TheQuadram

- https://twitter.com/NarbadLab