Dr. Olivia Champion is a research fellow at the University of Exeter. She is also the co-founder and CEO of a university spin out company called BioSystems Technology. Olivia is a bioscientist whose research interests include bacteria that cause infection in humans and animals and how we can better detect, prevent and treat infections.

Olivia spoke at the Exeter Soapbox Science event, which took place on Saturday 11th June 2016. She talked about: “Microbes: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly.”

Witnessing a case of typhoid changed my career path for good: From optician to bioscientist…

I am a research fellow at the University of Exeter and more recently I have also become a founder and CEO of a university spin out company called BioSystems Technology. My research interests include bacteria that cause infection in humans and animals and how we can better detect, prevent and treat infections.

The route to my current position started with a gap year after A-levels during which I travelled to Nepal and India for a year. Before setting off I had a deferred entry position at Cardiff University to study optometry as I was planning to go into the family business; both my father and grandfather were opticians. However, during my time in Nepal I lived with a family and the mother of the family became really sick with typhoid fever.

Fortunately she recovered but I remember thinking how ridiculous it was that people were still dying from drinking dirty water. It was that experience that changed the course of my career. When I got back to the UK I changed courses and studied applied biology rather than optometry in Cardiff. After graduating I worked as an intern for the World Health Organization in Geneva for the summer before getting my first proper paid job as a trainee clinical scientist in London at what is now called Public Health England (PHE).

It was around this time that I married my boyfriend, moved from my home in Torquay to London and as a trainee I was sent around the country to learn the skills, techniques and meet the scientists in a range of specialist laboratories; I also spent a year working on secondment in the North Middlesex Hospital in the Diagnostic Microbiology lab where I discovered that tuberculosis is alive and well in London, and all the while I was studying part time for an M.Sc. in Clinical Microbiology at Queen Mary and Westfield University.

Avoiding a career glass ceiling

Eventually my line manager at PHE suggested that I ought to do a Ph.D., as without one I would hit a glass ceiling in my career. I carried out a Ph.D. at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) supervised by Professor Brendan Wren and funded by an MRC [Medical Research Council] studentship. Towards the end of my Ph.D. I went to a conference where I met some professors who offered me a position working jointly between their laboratories at the University of British Columbia (UBC) in Vancouver: Professor Erin Gaynor and Professor Brett Finlay.

I was all set to move to Vancouver when I discovered that I was, very unexpectedly, pregnant! We made the decision to move to Vancouver before the baby arrived as I felt uncertain whether I’d still want to make the move after the baby had come along. It put a lot of pressure on me to write up, pack up and do a viva but we flew out of Heathrow the day after I defended my thesis as after that I wouldn’t have been allowed to fly on medical grounds as I was too heavily pregnant.

We arrived in Vancouver and after a period of maternity leave I started my first post-doctoral research at the University of British Columbia. Although I could have stayed longer at UBC, we made the decision to move back to the UK for personal reasons. We moved back to Devon and I joined Professor Rick Titball as a research fellow in his new group at the University of Exeter.

I’ve been happily working in Exeter for nearly a decade and have had a further two career breaks for maternity during that time. Over the past year or so I have been working towards commercialising some of my research and this has led to the establishment of the University of Exeter spin out company, BioSystems Technology.

Understanding certain bacteria better with the aim of developing vaccines and cures

The job of a researcher is to create new knowledge and then, where possible, to try to use this knowledge to solve real world problems to make a positive impact on society. Taking my own research as an example, my job involves trying to answer questions about bacteria that will help us to understand them better. We can then try to use this knowledge to inform strategies for detection, prevention and cure of bacterial infections in animals and humans.

One of the most interesting parts of my job is coming up with the research question in the first place. There are lots of interesting questions to be answered about one of the bacteria that I work on. Burkholderia pseudomallei is a very nasty bacterial pathogen, found in equatorial regions, that kills around 50% of people who become infected with it, even after they’ve been treated with antibiotics for 20 weeks.

If you are lucky enough not to die from the primary infection then you may well die from a recurrent infection as the bacteria can survive latently in the patient or cause a chronic infection once he or she is infected. Burkholderia pseudomallei is highly resistant to most antibiotics and there are no vaccines to prevent infection and it is considered to be a bioterrorism threat.

All of the information that we had until recently was about what Burkholderia pseudomallei “looked” like when it was causing acute infections. However, it is thought that the ability of the bacteria to survive latently in a host and to cause chronic infection and may be one of the reasons that it has not been possible to develop an effective vaccine. To answer this question I set up a series of experiments, the results of which built up to provide an answer.

The results of this study were recently published in a Scientific journal called Vaccine and the real world relevance of this work is that we now have additional information that can help us in our aim to develop a vaccine against Burkholderia pseudomallei to prevent infection. However, as is often the case, the results of this research have produced a lot more questions that now need to be answered.

Passionate about microbes

My Soapbox Science talk is about microbes; the good, the bad and the ugly. We often focus on how bad microbes are for us and it’s possible to become slightly paranoid about hygiene but many microbes are beneficial. Bacteria and fungi are used to produce some of the nation’s favourite food and drinks. Also, our intestines are packed full of important microbes that help to keep us healthy. However, some microbes are bad for our health and they can make us sick and even kill us.

It’s easy for us to forget about the devastating effects of some of the nasty bacteria because we live in an era where childhood vaccination is routine. But we should not forget that more than 732,000 children’s lives have been saved and 322 million cases of illness have been prevented in the past 20 years from routine vaccinations (source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention).

‘Good’ bacteria, ‘bad’ bacteria and life sized microbes

In my talk I will introduce the audience to the idea of bacteria, the importance of ‘good’ bacteria and the dangers of the ‘bad’ bacteria; I will show the audience what some bacteria look like, how easily they grow and spread, and also about the importance of antibiotics and the causes and danger of antibiotic resistance. I’ll also talk about programmes that are underway to discover new antibiotics and how the general public can get involved with this.

To prepare for the event I am testing out ideas for audience participation on my friends and family. I have three children aged ten, seven and two and they are all very keen to get involved. In fact, it’s going down a storm. I have also been in touch with the outreach officers at the Microbiology Society who are looking into some props that they can let me use for the event.

Breaking down the barriers between scientists and the general public

Soapbox Science is a fantastic initiative that promotes the breakdown of gender stereotypes, supports female scientists and provides positive role models for children. These aims are really important for both science and society as a whole, not just in the UK but around the world.

Science outreach events also have wider role in improving the relationship between the general public and scientists. There can still sometimes be a distrust of scientists by the general public. Outreach events such as Soapbox Science show the general public that we are, for the most part, normal, hard-working people who have pursued an interesting career because we have inquisitive minds and we want to solve real world problems.

Academic progression – still way out of kilter for women

When I was a girl I didn’t perceive that sexism was really a problem anymore. I felt that there was nothing to stop a woman from succeeding in her ambitions so long as she worked hard and had a “can do” attitude. However, the evidence shows us that regardless of hard work, female scientists are far less likely to secure a permanent academic position compared with their male counterparts.

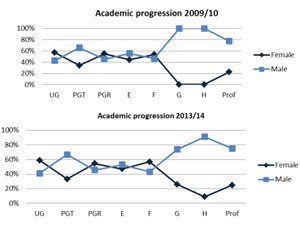

Data collected from universities across the UK on the gender split during academic progression in STEM disciplines highlights the problem and the diagram exemplifies the situation. ‘Grade F’ is the last point in a researcher’s career progression before tenure. (In higher education, ‘tenure’ is a professor’s permanent job contract, granted after a probationary period of six or seven years.)

This shows us that there are equal numbers of men and women working on fixed term contracts at every point until ‘Grade F’, after which the number of women drops dramatically. To women entering a career in academia with ambitions to become a professor this makes sobering reading.

Addressing the many reasons for gender imbalance

The reasons behind the stark gender imbalance in academia are now being investigated and appear to be dependent on a number of factors.

Obviously there is the fact that the female reproductive window of opportunity coincides with the point at which she’d finish her education and would ideally put her foot down with her career. But, career breaks for maternity leave and the on-going disruption of juggling family life with a career, the need for flexible working hours and good child care are not the only factors at play.

Many talented women without children do not secure tenure and conscious and unconscious discrimination may be a factor in this. Worrying evidence by an assistant professor, Corinne Moss-Racusin and colleagues published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS) in 2012 reveals outright sexism by academics who favour male students.

The current spotlight on gender imbalance in science is thanks to the Athena SWAN charter that promotes gender equality and which was championed by Dame Sally Davies, the chief medical officer and chief scientific advisor in 2011. Dame Sally Davies placed a financial incentive on academic institutions to address their gender inequality issues by restricting the award of research funding to only those institutions that had achieved an award of the Athena SWAN charter for women in science.

However, despite the obvious gender inequality in science and the positive role of Athena SWAN in addressing this important issue there is still some resistance to the charter in the work place. This resistance comes in part from senior academics who see Athena SWAN as a politically correct annoyance.

However, there is also some resistance from younger women who may still be blissfully unaware of the glass ceiling that their heads are about to crash into. Many of the women who object to Athena SWAN are either too young or too junior to have been affected by any of the issues that Athena SWAN aims to address. Yet, ironically, in time these women will become the very people that the charter is trying to protect.

This opposition to Athena SWAN creates a culture in which it becomes difficult to tackle the issues and consequently slows progress. It also disheartens the women who are at the glass ceiling and are trying to have their voices heard. There needs to be an overwhelming support for Athena SWAN, not just as a tick box exercise, but to entrench the equality charter’s aims into the fabric of institutions to create a more equal society.

From a research career to start-up business … I’ve learnt a lot very quickly

Over the last 18 months or so I have been busy commercialising some of my research. Together with my co-founder, Professor Rick Titball, I have pioneered a system which provides low cost, high-throughput, ethical solutions for researchers who require alternatives to animal testing. We recently formed a start-up company, called BioSystems Technology and we have just started marketing our product, TruLarv, in the UK and Europe.

It’s been a very steep learning curve, moving out of the laboratory, where I have been focused exclusively on research for over a decade, to become co-founder and CEO of a start-up company. However, my business idea was picked up early on by the Research Knowledge Transfer (RKT) Group at the University of Exeter. Through RKT I was introduced to a business mentor who guided me through the pitfalls of entrepreneurism and I have also been well supported by the business incubator, SETSquared.

Winning investment

Next up for me is a period of focus and hard work on growing BioSystems Technology. In November I pitched for investment for BioSystems Technology at a Dragon’s Den-type event and I am delighted that we have now received £200k in investment from private backers who bring a huge amount of enthusiasm, energy and experience to the team and we look forward to growing the business in the UK and Europe over the next few years.

http://biosciences.exeter.ac.uk/staff/index.php?web_id=olivia_champion

https://www.biosystemstechnology.com/

https://twitter.com/_biosystems

World Health Organization, Geneva image credit: By Thorkild Tylleskar (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons