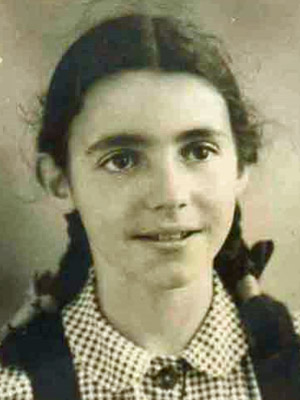

Dame Stephanie “Steve” Shirley is a British businesswoman and philanthropist who came to Britain from Germany in 1939 as a Jewish child refugee and was placed with foster parents living in the Midlands. She chose to go straight into work when she finished school, going on to obtain an Honours Mathematics degree by studying at night school for six years. In 1962 she founded her all female software company Freelance Programmers, which later became Xansa plc, with the equivalent of $100 in today’s money – a company that eventually went on to become worth £3 billion and made 70 of the staff millionaires.

“…I dressed in a grey suit with a white blouse with a velvet ribbon round my neck like a vestigial tie. Those days have passed. Women can be themselves, dress for themselves, and most employers now recognise that diversity of skills brings out features that they just wouldn’t even think of with the men only. So we have a lot of opportunities…”

Dame Stephanie, we’re very keen to talk to you with your entrepreneur’s hat on today. Please could you tell us a little about starting your business in the 60s as one of the first ever social businesses?

It certainly was a social business because I seriously considered having it as a charity. But I realised that it would never be respected in the same way and that I needed to make it into a business that earned its own keep, sorted out its own cash flow and became respected as a business, not for its social purpose.

It started as a crusade, and people were sniffy about it, but to me it was a crusade. I was going to make opportunities for women with children and Minute Number One in the company’s annals was, “Jobs for women with children.” And then I learnt how important training was and it changed to, “Careers for women with children.” Then I realised that a lot of women in those days were starting to look after elderly parents or disabled partners, and so it became, “Careers for women with dependents.”

In 1975, of course, Equal Opportunities legislation came in and you couldn’t have a pro-female policy like that and we had to let the men in (as long as they were good enough!) and thereafter it gradually became well balanced between the sexes. Which is as it should be really! It’s much better if you’ve got a good balance.

It started with all women. When we were 300 strong I think there were two or three men, but we finished up with 8,500 people and by that time it looked like any other corporate – sort of half and half, but the women clustered in the lower levels of management. The seniors were predominantly male – with only one or two women on the board. But, that’s how it goes…

You’ve written and spoken about your experiences in childhood as a refugee from Nazi Germany who was helped by generous strangers and how this made you want to make your life “a life worth saving”. There’s a C.S. Lewis quote, “Hardships often prepare people for an extraordinary destiny.” Do you feel this is what drove you to break down so many barriers for women in the workplace?

I hope I would have been doing something similar anyway because the family’s always been humanitarian, but the sheer drive it gave me and the ability to deal with the minority issues. Jews were viewed as second class citizens; women were viewed perhaps as third class citizens. The trauma of that childhood experience, coming to England as an unaccompanied child refugee, was very strong and is as strong today for me as it was 75 years ago.

Clearly I got that kernel of toughness – if I could cope with something like that, if I could manage all the changes – different families, different language, different food, different everything – if I could cope with all those sorts of changes, I eventually became keen on change. I like change. I’m easily bored. It’s such a strong driver for me today, so I think hardship does make a lot of difference and ‘toughness’ comes early on for people.

At your girls’ school you weren’t offered the opportunity to study maths, so you were given permission to take lessons at the nearby boys’ school. How does it make you feel to hear about the challenges in keeping girls studying STEM subjects at A Level and university? What attracted you to maths?

I spoke at this year’s Sunday Times Festival of Education, and that was about encouraging more girls into the STEM subjects because there’s a theory or feeling that the science subjects are nothing for girls.

In my day, the only science that was respectable for a young girl was biology. I had so much trouble and I had to change schools twice to get tuition in maths. I love mathematics and it’s the basis of so much science, and in a way one hopes that teachers could just teach mathematics before they start to diverge into physics and chemistry and biology. They’re all rather different, but the commonality of course is mathematics. There’s quite a way to go still in getting a culture in which girls and young people enjoy science.

Not that anything is actually held in front of us to stop us, but there’s a culture that mitigates against us. One of the other things I spoke about was that’s it’s been observed for both male and female teachers that they encourage the boys more in science.

They smile and nod at them more often, they ask them more searching questions, they ask them to serve as assistants in demonstration experiments. They call on the boys more often and wait longer for the boys to answer. That is a terrible cultural thing, but a good teacher, if you show them a film about unconscious bias, will determine, “I don’t want to be like that.”

There are ways you can correct that. A simple way is for a teacher to ask questions of a class and ensure they ask a boy, and then a girl, a boy and then a girl, so the girls get enough chance. Although I have serious worries about sexism, it is improving. It’s a lot better than it was in my day.

I think one of the American ways of doing things is to rejig the curriculum in such a way that you have lessons called, ‘engineering and music’ or ‘mathematics and art’ and so really integrate STEM subjects into the rest of the curriculum. Different countries approach it in different ways.

In one way Britain does quite well – worldwide we’ve got about 1% of the population and 10% of the innovation, so we’re doing alright! On the other hand, when it comes to engineering, we’ve got something like 6% of engineers are female, and in Russia, the former Soviet Union, they have got 58% ─ more women than men, so there’s nothing intrinsic that says that if you’re an engineer you have to be male. Engineering’s not oily rag stuff anyway.

You’ve talked about your company being a search to get you out of poverty rather than to make you wealthy; and the frenetic activity this involved. Would you say the motivations of female entrepreneurs differ significantly from their male counterparts in terms of attitudes to risk etc.?

It’s not an informed opinion, but women take a longer viewpoint, that we’re not after short term gain but rather a long term vision. There seems to be more capability of dealing with international issues and when it comes to risk, the stereotype is of risk aversion for women, but I’m not sure if that’s true.

In my own case, I was prepared to risk a vast amount – including our house – on something I believed in, but when it actually came to risking the whole company on something, I wasn’t prepared to do that.

There was the opportunity to become a ‘Name’ on the London Stock Exchange, in a system where you didn’t have to put up any money, you just showed that you had serious money. But had it failed, the company would have gone. And that I wasn’t prepared to do. It surprised people. I was wise actually, because a lot of other people did lose their money, but that’s more risk averse than people expect of an entrepreneur. It was highly emotional. Gamble the company? No!

You famously changed your name to “Steve” in your business development letters in order to build your business. Hopefully things have improved slightly(!), but how can women in business differentiate themselves today?

I can only advise that they make sure that they don’t differentiate themselves as an ‘honorary man’, because that’s what I was told. “If you’re going into the City, never forget that you’re an honorary man”.

I dressed in a grey suit with a white blouse with a velvet ribbon round my neck like a vestigial tie. Those days have passed. Women can be themselves, dress for themselves, and most employers now recognise that diversity of skills brings out features that they just wouldn’t even think of with the men only. So we have a lot of opportunities.

Lots of what we write about is trying to help women find their professional passion. What’s your advice to women looking for theirs and how do you know when you’ve found it?

You certainly know when you’re found it. You really do. It’s rather like with children, I suppose – you expose them to all sorts of experiences just to see if they like them and that’s how they learn what they want to do with their lives. We just have to try lots of things. We have a choice in life. We need to surround ourselves with people who are first class, but also with people that we like (not necessarily like you). We do have that choice. We don’t have to follow the herd and I believe in that way we will find our passion.

Some people never do, but when you do find your passion you – will – know. It’s like falling in love.

I came across a group of young people at Oxford who actually knew they wanted to be philanthropists; they knew they wanted to do good in the world. They considered whether they wanted to spend the 80,000 hours of their working life making money to later give away. Or should they be working early on with charities? I thought it was a very interesting question.

There is no preferred answer. My company is socially orientated – we joined something called the PerCent Club, which guaranteed we would give, I think it was 2% of the pre-tax profits to charity every year. I can remember discussing this with my board who asked the obvious question, “How much are we spending at the moment on charitable activities?” And I did not know. So I went and found out and we were already spending much more than that anyway, it’s just we needed to put numbers on things!

I believe philanthropy to be part of who you are. I’m certainly entrepreneurial. I’m not money motivated. I know I’ve got to have money and it’s got to be positive. I know it’s very uncomfortable to be poor. I have been really poor and I never want to be poor again, but the rest is lovely to have.

I’m just so, so lucky, but mainly I’m lucky to have something to get up for every morning. I have a very active life, which in their 80s most people don’t have. There are things to do and exciting new experiences. It’s just lovely and all that comes from looking outwards, not thinking what I want, but what does society want that I can possibly help to provide.

You were driven to set up your business as your first boss showed you what you didn’t want to be! How good are companies at ‘doing as they would be done by’?

I was always inspired by the John Lewis Partnership and am proud to have been their first ever non-executive director. It’s a predominantly female company, being retail.

There is a company that has always differentiated itself and has done brilliantly compared to the competition through its social conscience. It does everything right. The concept of ‘fairness’, we’re all partners, we’re doing this together. I can help you this morning and you can help me this afternoon – together we will make it happen. That’s very important and good businesses are like that.

We were sorry to hear about the loss of your son, Giles, who had autism. You’ve talked about setting up Prior’s Court School in order to support other parents caring for children with autism and your charity, Autistica, is carrying out pioneering research on the condition. What’s next in your work in this area?

I started off with a charity called Kingwood, which looked after my son and now a hundred like him. Prior’s Court, which has something like 500 staff, is another sizeable organisation now and has pupils aged 7-25 as an educational establishment. But the most significant and strategic is Autistica, which funds medical research into autism: to understand what autism is as distinct from what it looks like.

I can probably recognise an autistic child from the other side of the playground. We still know very little about autism and that’s the research that Autistica funds. As is good marketing practice, a couple of years ago they did a 1000-family survey of individuals and families affected by this disorder and found out what they wanted, rather than letting the boffins decide for them.

This came out with three clear themes – firstly, earlier diagnosis, which I think I could have guessed that families would always want. We know if we start quality interventions earlier it will help. They’d already started that work and it’s largely done by Manchester University. There’s a feeling now that autism itself isn’t so bad, it’s all the things that go with it – the mental health issues, their over sensitivity to light, to heat, to noise.

The second theme is a study of autism and mental health – one in four people in this country suffer from mental health problems at one time or another. Most children with autism suffer from mental health problems. That is work being carried out with the Institute of Psychiatry, which is part of King’s College London.

The third one – because up to now whatever work has been done researching autism has been with children – the third prong is really to understand what happens to the autistic brain as it ages. There are odd things that we know – that women are tending to have menopause earlier. What does that tell us? Another study has shown that women die younger than men, statistically significantly. Since normally we outlive the males, what is happening there? So that’s the third prong. Those three are what Autistica is funding now.

I have, not a theory, but a way of living – I start something, I get it sustainable and then I really back away from it and go and do something else. My first charity took me 17 years, Prior’s Court took five years, Autistica took two years to get managerially and financially independent of me. So I now get invited to their events, I fundraise for these charities, but I’m not involved with them.

So what am I doing now? Well, last year I set up a Think Tank called the National Autism Project, which is going to come up with an independent, authoritative report on autism and then the next 18 months is planned to lead towards a national strategy for autism. As part of that there’s a Parliamentary Commission on autism.

So all of this is driving it forward to see if one can be positive about autism, with thinking in terms of people with autism getting into employment, not necessarily sheltered employment, but certainly in the IT industry for example, many people with autism have just the sort of skills that are needed. But they’re difficult to employ. They may be difficult, but if you can make the surroundings acceptable to them and it you can get through banal things like the interview process (which is not a good way of selecting them), they really become quality, loyal, reliable staff.

The first meeting of the National Autism Project, we had people with autism there and they came up with something so important that we’d completely missed (we being two or three people who has put the agenda together). They had an absolutely orthogonal approach.

As you’ve now focused on philanthrophy, do you miss any of your previous corporate life?

There are more similarities than people imagine. You’re doing much the same, it’s just the values are different – you’re not going for profit, but for social values. Yesterday I was with a company in the City and I liked the atmosphere, the lovely reception – there’s a sort of buzz about it. It was an IT company and whilst yes, I really enjoyed that, I wouldn’t want to go back there.

Basically, in philanthropy I come across a very different type of person. I really enjoy and value all the people that I come across.

We loved your recent TED talk! What was it like doing this and what has the response been like?

They always said to me, “We want the very best talk you’ve ever done.” No pressure! And to a certain extent they got that because it was prepared very carefully. You only have 14 minutes and you have to get every word counted for example. I usually rise to a challenge!

https://twitter.com/damestephanie_