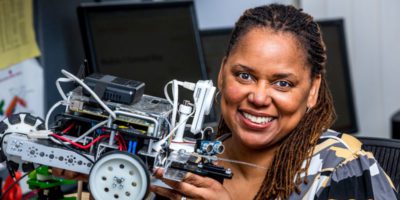

Dr Caitlin Bentley joined the Information School at the University of Sheffield in 2020, as a lecturer in AI-enabled information systems. Prior to that, Caitlin worked at the 3A Institute, Australian National University, where she contributed to the development of a branch of engineering to manage artificial intelligence at scale and make a positive impact. Caitlin previously worked within the area of information and communications technologies for development.

“We need to take a step back and examine our current systems and structures, to recognise that AI alone is not going to change the way things work, and that if it boosts or amplifies certain processes, it can also boost or amplify inequalities or things that do not work well.”

Developing my passion for culture, but experiencing the same issues

I tend to call myself a pracademic nomad, as I have oscillated between education and career, pursuing different disciplines and jobs as I grew and learned.

I graduated from McGill University, in Montreal, with a degree in computer science. I wanted to work for Google, but the tech bubble had just burst, and jobs were difficult to come by.

I took a volunteer-based internship with Oxfam-Québec through Canada’s netCorps programme, and I travelled to Morocco to work for a women’s rights organisation. I built them a website and gave technology training.

I often say that this experience burst my bubble: I learned about the richness of different cultures and people, and also witnessed some horrific abuses against women’s rights. I was harassed a lot myself, and I didn’t know if it was really the type of work I could do forever.

I decided to do another placement in Mozambique, this time with a mining workers’ rights organisation, doing the same type of work. Whilst there, I continued to develop my passion for culture and development, but I also started to notice similar problems that the organisations I was working for faced.

Tech is only one small piece of the problem

I wanted to learn about how people from different cultures learn to use technology advantageously, and I went back to university to study a master’s of educational technology at Concordia University, in Canada.

I then started working for a Canadian international cooperation organisation called Crossroads International, where I stayed for four years. We developed new technology and projects to facilitate greater South-South cooperation between our development partners in West Africa.

This was at a time when Internet was scarce (and it still is in many of the places where we were working). Now, we can use technologies like Skype or WhatsApp easily, but back then it was an achievement just to help our partners communicate via videoconferencing on very limited bandwidth.

From that experience, I observed more issues that partners were facing due to the international aid funding system, and I wanted to use my skills to ease some of these wider systemic problems, so I went back to pursue a PhD in information and communications technologies for development (ICT4D) within the geography department of the Royal Holloway, University of London.

My dissertation explored how technology influences learning and accountability processes in relationships between civil society organisations and bilateral development donors (bilateral donors are usually governments, international financial institutions and other partners) Ultimately, I learned how deeply complex some of the problems I wanted to fix are, and that technology is only one small part of the puzzle.

Transformational research in Singapore and Australia

I then took a postdoc (a temporary position that allows a PhD to continue their training as a researcher and gain skills and experience that will prepare them for their academic career) at the Singapore Internet Research Centre to contribute to a programme of research on open development, which is the free and public sharing of information and communication technologies towards a process of positive social transformation.

In 2015, it seemed like there was real potential to transform governments and institutions through open innovations (like open data, open educational resources, or crowdsourcing). Yet, we witnessed instead a turn towards privatised platforms for information sharing and communication.

We also saw the emergence of new AI technologies, which seemed to be entering our lives and societies without much discussion or consideration at all.

In 2018, I started working for Australian National University’s Autonomy, Agency, Assurance Institute (3A), led by a distinguished professor and senior vice president at Intel, Genevieve Bell. There, I hoped to influence the way that AI technology is designed and to contribute to the establishment of a new branch of engineering that will help to take AI safely, responsibly, and sustainably to scale.

Feminist AI

For personal reasons, I needed to move back to the UK, and I was incredibly lucky to have obtained my current job as a lecturer in AI-enabled information systems at the University of Sheffield. Here, I will continue to lead conversations around AI in context, and how we can ensure that our systems incorporate AI inclusively and sustainably.

As a lecturer, I teach on two master’s programmes, and I supervise students to complete their dissertations. I also work on developing my research portfolio, by writing grant proposals, publishing articles, reports, and books, and managing my current projects.

At present, I am working in two key areas: I am contributing to the Women Reclaiming AI activist network, which is a network that has run a series of workshops to engage women in discussions around AI, and in which they develop a conversational AI chatbot coded entirely by self-identifying women. You can speak to the chatbot on our website.

We are also creating new forms of feminist AI methodology, as a means of debating what it means for an AI to have an identity, or how women wish to be represented in AI technology (or not). Ultimately, we hope to engage more women in the field.

Secondly, I am working with a fabulous team on a project to map data systems around the circular economy in developing countries. This, we hope, will lead to developing AI technology that is responsive to improving circular economies in ways that promote greater social inclusion as well.

Partnerships are crucial

I tend to work with partners in the development sector. Most recently, I worked with the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data and the Inclusive Data Charter on a project around intersectional approaches to data.

I have received funding from the Royal Academy of Engineering for the circular economy project, and we are working with Libe Green Innovations on that project as well.

My prior work on AI for social good was funded by Google.org, managed by the Association of Pacific Rim Universities (APRU) and supported by the UN Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP). I would like to work more with companies and social enterprises in the UK.

Starting a new role during the pandemic

I started my job at Sheffield in August 2020, and I have still never met my colleagues. I’ve only been to my office once. It has been incredibly difficult to learn how to do my job whilst having to find everything online, or to know who the right people to ask are. For those of us that work in the development sector, it’s challenging also to see partners struggling due to COVID, and to see the impact of the cuts to official development assistance (ODA) funding have had. With travel being limited, it means we have to change the way we do research entirely.

Using AI to facilitate the things we value

The thing that my former colleague, Genevieve Bell, articulates so well (and you should watch her TED talk if you haven’t already) is that AI is already amongst us, it is already being implemented in our homes, our work environments, our schools, our transportation systems and environments.

For me, it is the fact that public debate has lagged behind these technological advances, and most of the discussion centres on the AI technology itself – whether it will replace jobs, whether it is fair, whether it is efficient.

We need to take a step back and examine our current systems and structures, to recognise that AI alone is not going to change the way things work, and that if it boosts or amplifies certain processes, it can also boost or amplify inequalities or things that do not work well.

If we begin with the systems to collect, store, manage and discard data, and focus on how we can make these systems safe and inclusive, we will be better off in the future.

The most impactful trends that I see will be those that enable people to gain the knowledge and skills to claim rights over their data, and to ensure that the data that is collected and amongst us is needed for the things that we value.

Honestly, if you lived in Sheffield for even a day, you might see that autonomous cars, in all their potential glory, will not impact the way that citizens like to park on streets, the way half the city seems designed for one-lane traffic. Do we really want to change the way we live to make it easier for autonomous cars to navigate?

Perhaps we might also want to build a system where our kids can get to school or to music lessons safely on their own, or go get grandpa for his medical appointment. Maybe other forms of transport will be more environmentally friendly, and shouldn’t we consider those? If we talked more about the systems and structures that we have and how we can make them better collectively. That’s the kind of impact I want to see.

Let’s bring more women into AI

Making AI systems more inclusive, especially from a gender perspective, needs to take a bigger priority for a more diverse group of actors, especially those who hold the power in different contexts, but I am hopeful.

I can only talk from my standpoint of a white woman in academia, I do not speak for all women, but I believe AI systems can be more inclusive if:

- First, we get more women and more people who are at risk of being marginalised into AI technology development roles, as well as in all the policy and regulatory decision-making roles that surround AI.

At Sheffield, we are building a new data science undergraduate programme that has this goal as a core focus. When you aim to include women and other marginalised people in data science education, what you might teach also has to change. So, I am very excited about this.

- Secondly, we need to give women the space to develop AI technology independently, as I think we can learn a lot from it.

I am very inspired by an interview that we did with Diane Bell, a prominent anthropologist in Australia, who showed that aboriginal women had independent bases of power in aboriginal communities. Women’s business is not equal to men’s, and it shouldn’t be.

I think in the work that we do with Women Reclaiming AI, we are developing a chatbot with a completely different identity, and with that, comes all the decisions about what the chatbot will do, who can use it, what can it be used for, and who can contribute to its development.

None of these questions are straightforward to answer if you approach AI systems from an equitable gender perspective.

- Lastly, we need to support community ownership and democratic governance principles in AI systems.

I am also greatly inspired by the work that IT for Change does towards this. These sorts of principles take different shape and meaning across cultures and contexts, so that is also something that I am really interested in learning more about in the future. There is a lot to learn and to develop.

To have a meaningful conversation with people is very important as well. We really need to build up people’s literacy about their data rights and what these technologies mean for their lives and societies.

Gone are the digital divide days, when the point was accessibility to technology. That is still an issue of course, but now it’s a point of contention that many AI technologies may enter our systems without much transparency or knowledge about it. That needs to change.