Dr Sumita Mukherjee is an associate professor in modern history at the University of Bristol. Sumita’s research focuses on the transnational mobility of South Asians in the British Empire era (nineteenth and twentieth century). In 2018 she wrote a book about Indian suffragettes, who are often not recognised for their campaigning.

“Women’s History Month is a great opportunity to highlight all the great work on women’s history that is out there, but it shouldn’t be confined to March!”

Celebrating modern Indian history

I have a PhD in history from the University of Oxford. My PhD looked at Indian students at British universities between 1904 and 1947.

Indian students were the largest foreign student body at the time and so I looked at their experiences in Britain but also what they did when they returned to India after their studies.

For example, the first woman of any nationality to study law at Oxford was an Indian woman called Cornelia Sorabji who returned to India to focus her legal career on helping women in purdah, a religious and social practice of female seclusion. My book about these students was published in 2010.

After my PhD, I worked at a number of universities including Oxford, the University of Glasgow and King’s College London before joining the University of Bristol in 2016.

Before joining Bristol, all my contracts were short-term (I’m now on a permanent contract) and that is one of the hard things about UK academia that many people don’t realise. A lot of us work on short-term contracts, which makes it hard to establish our career but also to do the kinds of research and teaching we want to do.

History today

I’m currently an associate professor in modern history at the University of Bristol. My role combines teaching, research and administrative duties. On the one hand, I’m involved in lecturing, teaching and supervising undergraduate and postgraduate students studying history at the university. On the other, I’m actively engaged in historical research, going to archives, and writing books and articles about my historical interests.

We also have to undertake administrative roles, some of this is the administration involved with designing our curriculum, setting exams and marking, but also in supporting the research and public engagement activities of colleagues. With libraries and archives closed, and limited opportunities for travel, the lockdown has meant that some of the research that I’ve wanted to do has been put on hold.

On the trail of the Indian suffragettes

I’d wanted to write about Indian suffragettes for many years but was only really able to do so once I won some UK Research and Innovation funding to do so in 2015.

This enabled me to visit archives in India, the USA, Ireland and Switzerland to dig out the international connections of Indian suffragettes. I spent over a year travelling and researching the lives and activities of Indian women who were involved in suffrage campaigns in India, and abroad, in the early twentieth century.

I should make a note about terminology here. ‘Suffragette’ is the term for the militant, often violent, suffrage campaigner in Britain. Their counterpart was the ‘suffragist’, who was more moderate and non-violent.

The Indian women I looked at were almost all non-violent in their campaigning, so technically should not be called ‘suffragette’, but it’s a label that was given to them and that has stuck and I felt it was a useful one to continue to use because of their radicalism.

Indian suffragettes should not be ignored

I’ve always felt that there was an assumption, especially in the UK, that it was only really British, Irish and American women who were involved in suffrage movements in the early twentieth century, ignoring the histories of women activists in other parts of the world.

There’s also been a nationalist narrative in India that men and women were given the vote equally once India won independence from Britain in 1947. However, my research highlighted that Indian women had been campaigning for female suffrage in India from at least 1917.

These Indian women involved in female suffrage in India were often ignored by Indian politicians and historians since, because the overwhelming narrative has always been about the freedom struggle overall. But Indian women were actively involved in campaigns on this issue.

Indian women involved in the British suffrage movement

What was most interesting to me, and the focus of my work, is that Indian women were also travelling around the world in this period to connect with other suffrage campaigners.

They did so to learn from women around the world, but also to gain publicity for their campaigns and to show women around the world that Indian women were interested and actively campaigning for women’s rights too. I discussed the connections that Indian women had with activists across Europe, the US, Asia and also parts of the African continent, Australia and New Zealand.

On top of all this, Indian women who lived in Britain in the 1910s were involved in the British suffrage movement.

The number of Indian women involved in the movement was larger than many realise, but what I have shown is that these women were often used by British women for show. So for example, Indian women (including

Lolita Roy and Bhagwati Bhola Nauth) were involved in a 1911 suffrage procession in London, but they were invited to attend so that they could look ‘exotic’ and for the British women to emphasise the expanse of the British Empire that British women, once they won the vote, would have a holdover.

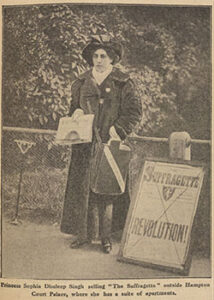

British women often ignored the fact that Indian women might want the vote – either in Britain or India – and were often quite patronising to women of colour. There were Indian women who were more actively involved in the British movement, like Sophia Duleep Singh, a leading member of the Women’s Tax Resistance League, and Susie Bonnerjee, secretary of the Ealing Branch of the Church League for Women’s Suffrage.

The intersectionality of social identities

It’s important to realise that we all have multiple social identities and that we’re not affected by just one social categorisation of ourselves.

A person or group might present themselves, or be challenged upon, their racial identities, but their class, gender, sexuality also come into play, i.e. they intersect. So, middle-class Indian women and working-class Indian women will have some common experiences based on their race and gender, but also differences because of their class. When we write about these histories then we have to be aware of these intersecting social identities.

Women’s History should not be confined to March!

Women’s History Month is a great opportunity to highlight all the great work on women’s history that is out there, but it shouldn’t be confined to March!

It’s the same issue with Black History Month or LGBTQ+ month. They’re great to concentrate and focus the mind on, especially for schoolteachers, but we should be discussing and highlighting these histories all year round.

Migration is not a contemporary phenomenon

I’m currently writing about Indian children who lived in Britain, and other parts of the world, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. This includes Indian school children at British schools in the nineteenth century, Indian children who were born to indentured parents in the Caribbean, and I’m looking at the women who cared for these children as nurses, midwives and mothers.

My mission is to continue to highlight the histories that show that Indian and other colonial peoples were migrant and mobile during the time of the British Empire, that migration is not a contemporary phenomenon and that Britain has been racially diverse for much longer than many people realise.

Within this, I’m continuing to emphasise that women and children were also actively involved in these journeys and they shouldn’t be seen as passive figures in history. I’m really excited about some of the stories of women and children that I’m uncovering and think there are some great role models for us all, whatever our background, in these histories.

https://sumitamukherjee.wordpress.com/