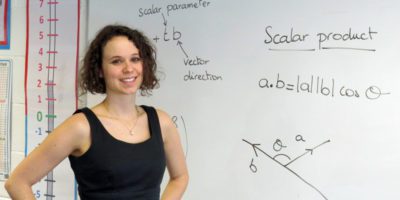

Cheryl Praeger is Emeritus Professor of Mathematics at the University of Western Australia and is Foreign Secretary of the Australian Academy of Science. She was formerly an Australian Research Council Federation Fellow and Director of the Centre for Mathematics of Symmetry and Computation. Her research has focussed on the theory of group actions and their applications in Algebraic Graph Theory and to Combinatorial Designs, as well as algorithms for group computation including questions in statistical group theory and algorithmic complexity.

“…I was only the second woman in Australia to be appointed Professor of Mathematics. My kids were still very young and I was 35. It was the most amazing thing to happen in my career…”

Becoming a real-life mathematician

I always liked maths at school but I had no idea that anyone could be a mathematician – I thought they were all dead! I just wanted to study as much maths as I could, having no idea whether it would lead to a job or not. I thought: “When I run out of opportunities I’ll do something else.”

I managed to get my honours degree and then my doctorate, and then a post-doctoral fellowship, and then eventually I got a temporary lectureship, followed by a tenured lectureship. I was appointed a full professor, succeeding Professor Larry Blakers at the University of Western Australis (UWA) about ten years after finishing my doctorate. I’ve had a really happy time being able to do mathematics.

Persisting to be allowed to keep studying maths and science

My dad didn’t understand that it would be really important for me to finish school, and he wanted me to study typing and shorthand, so I said: “Well that’s OK as long as I can study chemistry as well,” but of course I couldn’t do both because the subjects were on different tracks. Mum talked with Dad for 18 months to persuade him that I should be allowed to study science and maths, so that afterwards, if I left school after Year Ten, I could perhaps catch up with my shorthand and typing at a business college, if that was what I wanted to do.

So, then I was able to study science and maths up to the end of junior high school, and by that stage I really liked it and got good marks, so I was allowed to continue and finish high school, which was great. I had two younger brothers and they were going to get preference. My mum and dad said: “If you get a scholarship you can go to university, but we can’t afford to pay for you to go because we have to keep the money for the boys.”

“Girls don’t do maths. They don’t pass” Oh yes they do…

When I was trying to find out about what I could do with maths I saw a careers adviser at a government bureau, and he told me: “Girls don’t do maths. They don’t pass.” I was talking to the adviser there and he showed me an engineering course, and I thought: “That’s nice, but there’s no maths after second year, so that’s still not good enough.” I just got really angry and I wanted to do maths even more, so Mum came to the rescue again. She spoke with friends and found out there was a place I could go at the university to talk about courses.

From being the only female student to eventually becoming the second female professor in Australia

There were ten women in the ‘Honours’ maths class at the beginning of my first year – out of 80 students in total. After three months, there was an exam, and from second term on there were just four girls left in a reduced class of 33. In the second year, I became the only girl in my maths class because my female friends decided they didn’t want to do the higher-level Honours maths stream – they wanted to go back to the ordinary level maths class. I was the only girl left in the Honours maths class of 20.

I got married during my post-doctoral research fellowship at the Australian National University (ANU) in Canberra, Australia. My husband, John Henstridge, was doing a Ph.D. in statistics at ANU and we both got temporary maths jobs at UWA for two years. The jobs were extended. Mine was made permanent, and then John got a permanent job in the Agriculture Faculty at UWA, so we stayed.

We had two kids and when the younger one was seven or eight months old there was an advertisement for a professor level post in “any area of pure or applied mathematics” at UWA. I was at lecturer level and this job as professor was about three levels above. However, the professor of statistics suggested I should apply. After a while I decided I would, and after waiting another ten months for an interview I was appointed. So, I made this great big jump over three levels. It turned out there had been 85 applications. I was stunned.

I was only the second woman in Australia to be appointed Professor of Mathematics. My kids were still very young and I was 35. It was the most amazing thing to happen in my career.

Maths is about solving interesting problems, and also persistence

My role is a mixture of all kinds of things. There’s some teaching in lectures for undergraduates, and there’s postgraduate supervision for students who are trying to get their doctorates by working on their own research projects.

Today I’ve just come from two hours talking with two research visitors from Iran – we were trying to solve a problem, and for me, that is what maths is all about – solving interesting problems.

Maths is also a lot about persistence. So, for example, the Ph.D. student I was supervising this morning was very persistent, but it seemed to me that she wasn’t going to solve a very hard part of the problem, it was just too difficult. I felt my role was to re-scope the whole project and say: “I think we should be looking more broadly. Why don’t you consider some of these research questions?”

The supervisor role is to have a big picture and to suggest new directions for the research, which will shed more light than doing calculations which are too hard and don’t work out. The students can get very depressed. They think that they have to solve the problem, whereas maybe that particular bit of the problem is not solvable just yet. It’s about framing the problems in the right way.

I also have a lot of service activity. I’m the Foreign Secretary of the Australian Academy of Science so there are many emails back and forth during the day about decisions to be made about things such as policy statements.

Why maths-related career possibilities are infinite

I look back at the advent of digital computation, which has completely revolutionised what you can do, and what society wants. When I was growing up the only options to work with a maths degree were an academic teaching and research job, or otherwise teaching in a school.

We knew also that some mathematicians became actuaries who advised insurance companies and superannuation companies, and I had been told by that government vocational guidance officer that the Australian State of Queensland only needed one actuary, and already had one. At that time, we really didn’t need very many actuaries because there wasn’t such a great amount of information that could be analysed. However, with cheap and powerful digital computation, and the easy availability of huge quantities of data, maths is needed everywhere (and in particular we need lots more actuaries).

Mathematicians are also needed in banking and finance. They’re needed in health to help with bioinformatics and to help analyse clinical trials. There’s so many more avenues where we need mathematicians skilled up and working alongside scientists, engineers, economists and others.

There’s so many possibilities for jobs. I have one student who should be writing up his Ph.D. but yesterday he started a three-month internship to see whether he’d like working in a particular company. I said: “Please write up your thesis or you’ll regret it if you don’t.” It just needs to get done! There’s such a demand for well-trained people, especially in STEM areas.

The rise and rise of women in mathematics

We need more female role models so students can see there’s a possibility for them to work in maths. There’s still quite a low number of women working in academia. This means it’s important for these women to have networks and connect so they’re able to talk about common issues that arise. Networking is important, and role models – all the things which are important also in every other minority area.

There are “women in mathematics” groups in most countries now, but in Australia it’s only been formalised for about five years, although we’d meet up at every conference for about the previous 15 years before that to get together and talk about things over lunch. European Women in Mathematics run their own conferences and I’ve been to two of them. I’d never even thought of going to a women’s only conference with only women speakers, but they were wonderful. It was a very different environment, a different feel.

Each lecturer was asked to spend a few minutes talking about how she came to be where she was in her career. We heard from amazing women, telling amazing stories, which made us feel connected with the speaker before she even started to talk about the maths. I think other general maths conferences could learn from that.

Science in Australia Gender Equity

About two thirds of the universities in Australia have signed up for the SAGE Pilot project (Science in Australia Gender Equity). It’s in its first year so we can’t yet judge the outcomes but the SAGE programme has support from the universities and the research funding agencies. The NHMRC (the National Health and Medical Research Council) insisted that universities accepting grants should have policies and practices that are equitable for all staff, and this has to be a good thing.

There was a real push to do something significant for women in science at the Australian Academy of Science because in 2013, out of the 20 new scientists elected as fellows, none were women. This came at a time when the Academy had its first elected female president. Everyone felt terrible! The Australian Academy of Science re-thought many of its policies and procedures as a result, and SAGE is one of the wonderful initiatives that is affecting the whole country.

Australia is the first country in the Southern Hemisphere where the Athena SWAN programme has been exported. The Australian SAGE coordinators have subsequently organised a special bilateral workshop in India, funded by the Australian Government, to discuss the Athena SWAN model. This involved a lot of female academics in India and it’s possible that some form of the Athena SWAN initiative may be trialled there.

I was in Tokyo two weeks ago, talking about women in STEM in Australia, so I mentioned this process. There were people from Japan, China, South Korea and many other countries who were all interested. Maybe it doesn’t exactly suit their culture but I hope that some aspects of SAGE could help them because they were all worried about the status of women in their countries.

For example, it seems that there may be particular problems for women feeling able to come back to work after having babies, because of difficulty in finding suitable child care places. There are several impediments for women in those countries who want to work. I hope that modifying the Athena SWAN / SAGE model might make an enormous difference to many women. It also creates more flexibility for working fathers too.

Maths is about team working and collaboration

There are so many different areas of maths that people can go into, following their interests. There’s a great need for them. Studying maths doesn’t necessarily put you on an academic track. It gives you the skills and capacity to move into industry or other sectors, and you can get a much better job if you have graduate expertise.

My research group goes on a three-day research retreat every year somewhere off campus. This year we went to a beautiful place in the middle of a national park about an hour’s drive from Perth. We all propose problems we’d like to work on together, and we have a “problem describing” session just before the retreat. Participants choose the problems they find most interesting to them.

As a result of the retreat, we’re working on new problems with new people – our postgrad students, our researchers, and our many visitors. We spend several days together at the retreat working on these problems, and we keep working on the most fruitful of them afterwards. It’s fascinating and it’s fun.

There’s a great amount of teamwork that’s part of maths. It’s something you think of in science but you don’t seem to associate with maths. It almost seems like an isolated subject. Certainly, some people do it that way, as they feel that their deepest work is done when they are undisturbed and they have long periods of time when they can think. We all understand the need for ‘thinking time’ but there’s also much more team work in maths these days than there was when I was new in my career.

We love collaboration. Some would say that’s more usual in women than men: that women like collaboration, they like teamwork, they like working together and seeing where a problem is going. They take turns leading the direction of the work.

Making sure academic careers in maths remain accessible to women as their careers progress

There are some problems here. These days there are roughly half and half, men and women, in maths at undergraduate level, and then fewer women at postgrad level because maths graduates have gone in different directions. However, there’s a particular issue for young mathematicians who aim for a career in academia.

It’s important to get international experience and to get a good place to do post-doctoral research, but that’s exactly the stage of life where women may be forming a serious relationship and having children, so there are many additional problems that may make it more difficult for them. In England, there are re-entry fellowships that make it possible to have a link with a university, even if the fellow doesn’t actually have a job there. This helps to tide women over for short periods in their careers.

After a few years in my research group one of my postdocs had six to nine months in Cambridge (UK) looking for her next role, so one of the maths societies gave her a special fellowship, where a small amount of money was given to a university, and she was given a formal connection with that university along with some travel money to get to important conferences. This made all the difference and she’s just secured herself a Marie Curie Fellowship for four years, so the small investment from that society has really paid off.

The best career advice I received

The best advice I received in my career, although it didn’t come at the start, was to suggest that I might think of applying for a professorship, as I mentioned earlier. I’d got to the stage where I was thinking: “That is the level I want to reach,” but I hadn’t even thought that I would get there in the next ten years. Then a colleague I greatly respected said: “I think you ought to consider putting in an application for that position.” That was very powerful advice for me.

I’d been doing a lot of research with this colleague. He was in a different area from mine and we were collaborating across the disciplines. He was the one who suggested I should imagine myself in this much more senior role and apply for the position.

It took me about three months to decide that I would put in an application because a professor’s job seemed so far beyond me. I was just about to be promoted to senior lecturer, and as it turned out, I was senior lecturer for ten months until I was interviewed for, and the offered, the job of professor. So, I jumped over the associate professor level. Having a suggestion that I might take this opportunity changed everything. Women often don’t consider themselves for certain desirable roles without a suggestion from a trusted colleague or mentor.

Future plans

I have formally retired this year (in the sense of no longer getting paid!). My colleagues at the university are organising a mini-symposium where some of my former students and colleagues will give lectures. That will be a lovely day. I’m having a lecture theatre named after me too, which is a great honour. I’m very excited about it!

One of my close research colleagues from Imperial College London will arrive next week, and we hope to make a lot of progress on a huge research programme we’re working on jointly. I’m very much looking forward to that – I like being busy!

http://www.web.uwa.edu.au/people/cheryl.praeger